The Illinois chorus frog is Missouri's largest chorus frog. It is chubby, with large, muscular, toadlike forelegs. The general color is light tan to tannish gray. There is a V-shaped mark between the eyes, a dark stripe from the snout to the shoulder, and usually a dark spot below the eye. On the back, behind the head, there is a pair of large, dark, irregular V-shaped markings; these are dark gray to brownish gray. The skin is rough or granular. The belly is white. The toe pads are small and round, and the webbing of the hind feet is poorly developed.

The breeding call of males is a clear, quick series of high-pitched, birdlike whistles.

Similar species: In the hylid family, nine species, in three genera, are native to Missouri:

- Acris, the cricket frogs, one species: Blanchard’s cricket frog;

- Hyla, the treefrogs, three species: gray treefrog, Cope’s gray treefrog, and green treefrog; and

- Pseudacris, the chorus frogs, five species: spring peeper, upland chorus frog, Cajun chorus frog, Illinois chorus frog, and boreal chorus frog.

Adult length (snout to vent): 1 to 1½ inches; occasionally to nearly 2 inches.

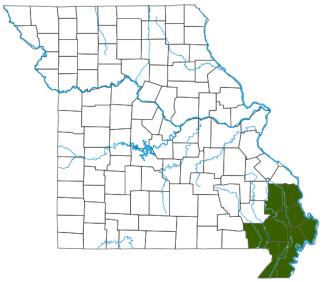

In Missouri, restricted to the southeastern corner. This species has a very limited range in North America, including only west-central and southwestern Illinois, southeastern Missouri, and one county in extreme northeastern Arkansas.

Habitat and Conservation

In Missouri, the Illinois chorus frog prefers flat, sandy areas. Originally, these frogs lived in the natural sand prairies and sand savannas of southeastern Missouri, but this habitat has been nearly eliminated. However, Illinois chorus frogs continue to survive in soybean and cotton fields in the former sand prairie region.

Illinois chorus frogs enter the soil headfirst, digging with their strong forelegs and forefeet. They are excellent burrowers in sandy habitat and can remain 6–8 inches below the surface for most of the year. During winter, they must burrow down more than 10 inches to survive cold temperatures. They tend to burrow in open areas away from any vegetation.

Breeding sites are flooded depressions in crop fields, roadside ditches, and other fishless, temporary pools.

Habitat changes and loss have led to diminished populations of this unique burrowing frog. See the Status section for more information about conservation.

Food

The tadpoles eat suspended matter, organic debris, algae, and plant materials.

The feeding behavior of adult Illinois chorus frogs is difficult to study because apart from breeding time, they are rarely aboveground. During the nonbreeding season, they usually eat while burrowing headfirst underground. They can grasp with their forefeet, which allows them to catch and hold prey. Apparently, during the months they spend living in the sandy soil, they swallow a lot of sand while they burrow and hunt.

A 1997 study showed the frogs primarily eating dingy cutworms (the caterpillar of a noctuid moth, Feltia jaculifera), which were notably abundant during the week of that study. However, these frogs also eat other species of moth caterpillars, plus beetles, spiders, true bugs, flies, and ants. Beetle larvae (grubs), in particular, frequently live in the soil and no doubt are an important food. Apparently, Illinois chorus frogs feed opportunistically on whatever insects they can capture — and most of their season is spent underground.

Status

A Missouri species of conservation concern, listed as imperiled by the Missouri Department of Conservation. Currently a candidate for federal listing by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It occurs only in parts of Illinois, the Missouri Bootheel, and in extreme northeastern Arkansas.

Extensive agricultural development in the historic sand prairie region of the Bootheel has destroyed or altered nearly all the natural ephemeral pools where this species once bred. Housing developments and other land uses have also reduced or eliminated the sand prairie sites.

Although this frog is still present in the highly cultivated areas of southeastern Missouri, these amphibians may not be able to withstand the continued destruction of their remaining habitat, especially of wetlands. Long-term persistence of this unique, burrowing frog in southeastern Missouri requires us to maintain the wetlands they need for reproduction.

Taxonomy: This frog was formerly considered a subspecies of the Strecker’s chorus frog and was called Pseudacris streckeri illinoensis; in 2004 the Illinois chorus frog was given full species status.

Life Cycle

Breeding is usually between late February and early April, depending on local weather conditions. Breeding sites are flooded depressions in crop fields, roadside ditches, and other fishless, temporary pools. The males call while floating in the water or hanging onto grassy vegetation. Females lay about 150–1,000 or more eggs, with an average of about 460. The eggs are laid in masses of 8–100 eggs. The eggs hatch in about a week. The tadpoles, which are large compared to those of other chorus frogs, may take up to 60 days to transform into froglets. Juveniles become sexually mature about a year later. Lifespan is about 2–5 years, but because these frogs spend most of their time underground, the lifespan may actually be longer.

Human Connections

Agricultural development in the Bootheel has destroyed nearly all the natural ephemeral pools where this species formerly bred, and housing development has nearly eliminated the sand prairie. This frog still lives in some highly cultivated areas but may not survive continued habitat destruction. The survival of this unique, burrowing frog in southeastern Missouri is dependent on maintaining the wetlands they require for reproduction.

Ecosystem Connections

Ecosystems have been likened to jets, with the various species of plants and animals as the plane’s components. If a species of gnat, grass, violet, or frog disappears, it might be like losing a rivet from a wing. A few missing rivets may not affect the jet’s ability to fly — but at some point, if enough components disappear, it will crash.