Blanchard’s cricket frog is a small, nonclimbing, warty frog that exhibits a variety of colors. Three color patterns are always present:

- a series of light and dark bars on the upper jaw;

- a dark triangle between the eyes;

- an irregular black or brown stripe along the inside of each thigh.

The general color is gray to tan, greenish tan, or brown. Down the back, there is an irregular stripe that may be green, yellow, orange, or red. The belly is white. The feet are strongly webbed, but the adhesive pads on fingers and toes are poorly developed. The chin of males is spotted with gray, and the throat may be yellow.

The call of males is a rapid metallic “gick, gick, gick,” like the sound of small pebbles being struck together. Calling may begin in mid-March. Although breeding activity generally lasts from late April until mid-July, the males may call day and night all summer.

Similar species: Missouri has eight other species in the hylid family. None are in the same genus as cricket frogs:

- Treefrogs (Hyla), three species: gray treefrog, Cope’s gray treefrog, and green treefrog

- Chorus frogs (Pseudacris), five species: spring peeper, upland chorus frog, Cajun chorus frog, Illinois chorus frog, and boreal chorus frog.

Adult length: usually ⅝ to 1½ inches (snout to vent).

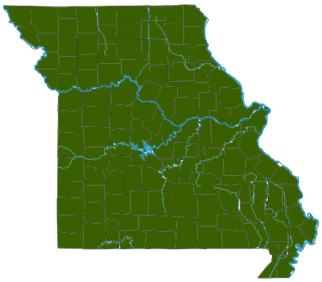

Statewide.

Habitat and Conservation

Blanchard’s cricket frogs prefer open habitats, especially sandy, gravelly, or muddy edges of streams, ponds, and lakes. They are rarely found far from water, but during wet spells in spring, they are occasionally found on glades.

In spring and fall, this species is active only in daytime, but in summer they are active both day and night. This tiny frog overwinters on land in crayfish burrows, in cracks of muddy banks and among tree roots, and in cracks on gravel slopes along ponds and streams.

These alert little frogs evade capture by a series of quick, erratic hops. When frightened, cricket frogs jump into the water but return quickly to shore. They sometimes feign death by posing head down, motionless, with eyes closed and limbs tucked in.

This species is gone or nearly gone from Minnesota, Wisconsin, northern Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, but the cause of this decline has not been determined. Missouri populations need to be monitored.

Food

Blanchard’s cricket frogs eat a variety of small terrestrial (land) insects.

Status

In the upper Midwest, populations of this species have vanished or significantly declined. Missouri populations tend to decline in drought years, but they usually rebound when rains return in following years. Blanchard’s cricket frogs remain common in our state, and their presence in Missouri seems secure so far. The species should continue to be monitored in Missouri.

Taxonomy: Blanchard’s cricket frog has a confusing history of scientific and common names. (Herpetologists, like ornithologists, use official common names that correspond exactly with the scientific name. When the scientific name changes, so does the official common name.) Don’t be surprised if you find this cricket frog listed, in older references, as Acris crepitans blanchardi; for a while, it was considered the same thing as the northern cricket frog, Acris crepitans.

Life Cycle

In Missouri, Blanchard’s cricket frogs are active from late March to early November. Breeding is from late April to mid-July. Breeding occurs in shallow water in ponds and river backwaters with plenty of aquatic plants. Warm temperatures stimulate males to chorus; both calling and nearby noncalling males can be successful breeders.

A female may lay up to 400 eggs. Eggs hatch in a few days, and tadpoles begin metamorphosis 5–10 weeks later, which is mainly in July and August.

The life span is rather short, with most individuals only surviving for no more than 2 years. Some individuals may live 3–5 years.

Human Connections

The distinctive calls of this species, like the sound of small pebbles being rapidly struck together, provide music day and night to Missouri’s outdoors. We hear them on float trips and calling from farm ponds and roadside ditches. We hear them in evenings as we gaze at stars, pondering the universe and our place in it.

Like other frogs, Blanchard’s cricket frogs prey on numerous insects that humans consider pests.

The naturalist Francis Harper named Blanchard’s cricket frog in 1947 to honor herpetologist Frank N. Blanchard (1888–1937). Blanchard taught zoology at the University of Michigan, formally described several new subspecies, and developed techniques for studying animals as they lived in nature. Blanchard’s cricket frog was one of several animals (species or subspecies) that were named to honor him.

Ecosystem Connections

Numerous predators eat the eggs, tadpoles, and adults of this species. Tadpoles have black-tipped tails that entice predators to aim for the tail tip as opposed to the tadpole’s head.

Spotted fishing spiders, giant water bugs, and predaceous diving beetles, which occur in the same shoreline habitats, may eat these small frogs and their tadpoles.