The four-toed salamander is a small, delicate salamander with a thick, round tail and four toes on both fore- and hind limbs. The snout is short and blunt. The general color is yellowish tan to brown on the back with many faint, irregular black spots. The sides are grayish brown with black stippling. The belly is pure white with numerous large, irregular black spots. The tail is distinctly constricted near its base. There are 13 or 14 costal grooves (vertical grooves on the sides of the body).

Similar species: This is the only member of its genus. Recent genetic analysis throughout the range of the species, however, has shown that there are six divergent lineages that may, upon further study, be found to warrant full species or subspecies status. Ancient or modern river drainages apparently acted as barriers to dispersal and interbreeding, leading to highly divergent genetic lineages.

Adult length: 2–3½ inches; occasionally to 4½ inches.

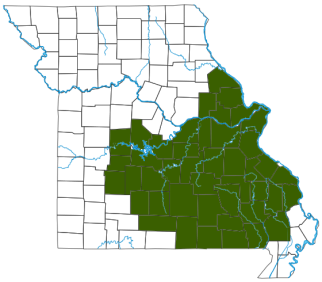

Occurs in the eastern half of the Missouri Ozarks, including the St. Francois Mountains. Small populations are also scattered north of the Missouri River in Warren and Lincoln counties.

Habitat and Conservation

In Missouri, this species lives among mosses along heavily forested headwater streams and spring-fed creeks associated with sandstone or igneous bedrock, and also in and along the margins of fens and natural sinkhole ponds. Occasionally, individuals are found along the margins of human-constructed ponds.

Away from egg-laying sites, individuals live under rotten logs, in leaf litter, or under rocks in seepage areas.

Elsewhere in its range, this species is associated with sphagnum (peat) bogs. This species has a broad overall range in eastern North America, including the Piedmont plateau from Alabama and Georgia north with the Appalachians into New England, southeastern Canada, and west to the Great Lakes region into Wisconsin and Minnesota. In addition to this broad range, many other states in the eastern U.S. have recorded disjointed populations of the species.

If captured, a four-toed salamander easily breaks off its tail and escapes, while the detached tail wiggles for a bit. Another defensive tactic is to coil the body and tail, tucking the head to the inside, and holding the limbs tightly against the body.

Food

Foods include a variety of small arthropods (insects, springtails, spiders, small aquatic crustaceans, and the like), worms, and mollusks (such as snails and slugs).

Status

A species of conservation concern in Missouri, due to its relatively low numbers, patchy distribution, and affinity to unique wetland habitats associated with moss. A number of new populations, however, have been discovered in Missouri in recent years, and it is likely the species is relatively secure in Missouri.

This species was listed as rare in Missouri for many years because of few locality records and because this species is recognized as a glacial relict. There are many disjunct populations throughout its range in eastern North America. Apparently, populations moved southward as glaciers extended south, then persisted in mostly isolated, suitably cool locations after the glaciers retreated.

Because of its spotty and highly localized distribution pattern across its broad range, this species is recognized with special conservation status in about 14 states and provinces.

Life Cycle

Breeding occurs in autumn. Soon after ending their winter dormancy, usually in the first two weeks of April, females move to a creek, ephemeral pool, or sinkhole pond and lay about 30 eggs in a protected pocket of moss, usually overhanging the water. They remain with the eggs until just before hatching, about 4 weeks. They sometimes nest communally, with two or more females' eggs together in one site. Newly hatched larvae have gills and enter the water.

The amount of time a larva remains in the water, about 3–6 weeks, is relatively short compared to other salamanders in the family. In Virginia, where they grow up in small woodland pools, the larvae can transform into juveniles in fewer than 40 days. Those that develop in streams, however, may take twice as long before they transform. It may be more than 2 years before they become sexually mature adults. Lifespan is probably at least 9 years.

Human Connections

Amphibians require water, where they mate, lay eggs, and develop into maturity. They are very sensitive to water quality. Human-caused water pollution, siltation, and other degradation, plus habitat destruction and fragmentation, threaten their survival.

Ecosystem Connections

This is one of several Missouri salamanders that live in caves, seeps, spring-fed creeks, fens, and sinkhole ponds. Taking care of our karst (cave, sinkhole, and spring) ecosystems and protecting groundwater quality is critical for them.

The defensive tactics of this species (such as the detachable tail, playing dead, and curling up in a ball) are a sign that many animals prey on it. Chief predators include shrews and snakes. As aquatic larvae, their predators include fish, aquatic beetles, and other salamanders. Eggs are eaten by a variety of animals including insects, centipedes, and other salamanders. Eggs are also digested by fungi.

The nest-attending behavior of females has been studied quite a bit. The presence of a female attending a clutch of eggs increases the survival of the embryos. Apparently the skin secretion of the females imparts to the eggs a resistance to fungal infection. Meanwhile, females apparently do not protect eggs from predators such as ground beetles, centipedes, or newts. Some researchers have suggested that the eggs might be unpalatable to certain ground beetles.

When communal nesting occurs (with two or more females' eggs together in one site), it may be due to a lack of ideal nesting sites. Because females do not seem to actively defend against predators, this may be an instance of predator dilution, like herding, flocking, or schooling behaviors, where individuals gain safety in numbers.

This is a member of the lungless salamander family (Plethodontidae). It’s a large family with 27 genera and about 443 species. The family probably originated in the southern Appalachian Mountains; its members now occur over the eastern half of North America, the West Coast, and into Mexico, Central America, and northern South America. A few species also occur in southern Europe and South Korea.

The "Out of Appalachia" hypothesis for the lungless salamander family is supported by recent genetic research on four-toed salamanders. The same study that determined that there are six distinct genetic lineages for this species also traced the common ancestors back to the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The lungless salamander family is named because the adults lack lungs and most lack gills; the oxygen they require is taken from their environment through the skin and mucous membrane of the mouth.