The prairie kingsnake is a medium-sized, tan or gray snake with numerous brown blotches. Up to 60 brown or reddish-brown, black-edged blotches occur along the back, with 2 rows of smaller blotches along the sides. In many individuals, the dorsal (upperside) markings are more like saddles or bands than rounded blotches.

Older individuals, especially in the southern half of Missouri, often have a darkened ground color. These darkened individuals often have their faded large blotches fused with the darkened ground color, making them look striped.

The top of the head usually has a rear-pointing, arrowhead-shaped marking, and there is usually a thin dark marking across the head between the eyes and down to the corners of the mouth. The scales along the upper and lower jaws as well as the chin are normally white.

The belly is yellow with rectangular brown markings.

The dorsal (upperside) scales are smooth.

Newly hatched young are lighter and more colorful than adults.

Note that this species is fairly common over most of the state, in a variety of habitats (not just in prairies).

When alarmed, a prairie kingsnake will vibrate its tail, which, if positioned among dry, dead leaves, can sound something like a rattlesnake's rattle. If captured, a kingsnake may try to bite to defend itself, but its bite is harmless.

Similar species:

- Young or newly hatched prairie kingsnakes often are confused with the venomous copperhead. Kingsnakes have round or saddle-shaped markings on the back, while copperheads have hourglass-shaped markings.

- Numerous other snakes are also camouflaged with gray, tan, brown, or black markings: Examples include the Great Plains ratsnake, bullsnake, and some of the watersnakes. Paying attention to the pattern of the markings, overall size, habitats, and ranges should help sort these out.

- The prairie kingsnake's closest relatives in Missouri are the eastern black kingsnake, eastern milksnake, and speckled kingsnake. All are in genus Lampropeltis, but none much resemble the prairie kingsnake in terms of color or pattern.

Adult length: 30 to 42 inches; occasionally to 56 inches.

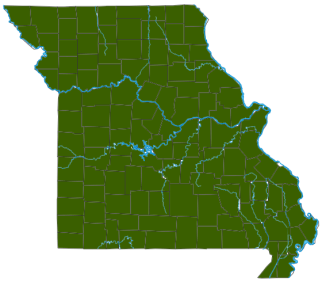

Presumed to occur statewide; less common in the southeastern corner of the state.

Habitat and Conservation

The name "prairie kingsnake" is somewhat misleading because this common, harmless species lives not only in native prairie habitats but also along the edge of crop fields, hayfields, fallow fields, or the edge of open woods, on rocky, wooded hillsides, near farm buildings, and in empty lots at the edges of small towns. They are secretive and spend most of their time underground in burrows or beneath sheltering objects.

The active season of this species is normally April to early November. Adult prairie kingsnakes may appear aboveground on sunny days during a warm winter, including in November, December, and February. In the spring and fall, prairie kingsnakes are active in the morning and early evening, but they become nocturnal during the summer. As with most kingsnakes, this species is rather secretive, hiding under objects such as logs, rocks, weathered boards, and old pieces of tin, or in small mammal burrows.

This kingsnake overwinters in dens in rocky, wooded, south-facing areas, road embankments, and burrows made by other animals. In northern Missouri, prairie kingsnakes commonly use crayfish burrows in dry upland prairies. They can also overwinter in mammal burrows. Most move to their overwintering sites starting in mid-September.

Food

The prairie kingsnake's chief prey are small mammals such as mice, voles, and shrews. They also eat lizards and small snakes. This species kills its prey by constriction. As with other kingsnake species, the prairie kingsnake is immune to the venom of copperheads, cottonmouths, and rattlesnakes. This species has also been found to prey on the eggs or young of ground-nesting birds.

Status

A relatively common, nonvenomous, harmless snake.

Prairie kingsnakes are considered beneficial, as they consume many rodents.

They are often misidentified as copperheads and killed out of unwarranted fear.

Taxonomy: At one time, three subspecies were recognized as part of the Lampropeltis calligaster group, and L. c. calligaster was the name applied to the snake in in Missouri. In 2017, all three subspecies were elevated to the level of full species.

Life Cycle

Mating occurs in early spring, in late March through early April, soon after emerging from winter dormancy, and extends into early June. Eggs are laid in June and July. A female may lay 3–21 eggs, with an average of 10, usually under rocks, in mammal burrows, under old logs and stumps, in old sawdust piles, or in plowed fields. Usually, only one clutch is produced annually, and not all females breed every year. The eggs hatch between late July and mid-September.

Prairie kingsnakes have been found to reach adulthood at age 2–3, with males maturing earlier than females. A wild-caught adult lived a little over 23 years in captivity.

Human Connections

Because the prairie kingsnake consumes many destructive rodents, it provides a valuable nontoxic rodent-control service.

Unfortunately, many prairie kingsnakes are killed by vehicle traffic on Missouri roads.

When alarmed, a prairie kingsnake will vibrate its tail; if captured, it may try to bite to defend itself. However, the bite causes nothing more than shallow scratches. When first captured, these snakes usually release musk from glands at the base of its tail.

The fact that kingsnakes, which are nonvenomous, can subdue and eat venomous snakes and are immune to the venom of copperheads, cottonmouths, and rattlesnakes, led to some interesting folklore. Vance Randolph collected and recorded the folklore of old-time Ozarkers before radio brought national popular culture to the region. Regarding the kingsnake, it was believed that it gained immunity to snake venom "because it eats rattlesnake weed as an antidote. The story goes that every time a rattler bites a king snake, the latter hurries over to a snakeweed nearby and nibbles off a leaf or two, before returning to the fight." Writing in 1947, Randolph continued, "I have never found anybody who claims to have witnessed this performance, and the whole thing doubtless began as a tall tale, but there are people in Missouri and Arkansas today who accept it as a fact." (The plant in question, in the Ozarks, is probably white snakeroot, Ageratina altissima, a toxic plant that folklore held to be an antidote to snakebite.)

The name "king," applied to this snake for its size and ability to fight and win against seemingly overwhelming opponents, is used in other animal names as well. The kingbird, for example, is famous for its spirited and seemingly fearless territorial defense against larger birds, including crows and even hawks. The kingbird chases and screams at its enemies, sometimes landing on them in flight and pecking fiercely on their backs. Kingfisher birds are named for their mastery of fishing and behavior of beating their prey against a perch before swallowing it. King mackerel are famous for their voracious, predatory appetites and for defending themselves against perceived threats by biting. These animal "king" names perhaps reveal more about our ideas of monarchy than they do about the animals.

The prairie kingsnake was described as a species from specimens collected near St. Louis in 1827.

Ecosystem Connections

Kingsnakes eat other snakes, lizards, and rodents, serving as a natural control of the populations of those animals.

As with many other predatory species, kingsnakes can themselves be preyed upon by larger mammals and by birds. The eggs and young are especially vulnerable. Predators of this species and their eggs include hawks and owls, other kingsnakes, raccoons, opossums, skunks, badgers, and domestic cats.