The prairie massasauga is a medium-sized rattlesnake associated with bottomland prairie habitats in north-central and northwestern Missouri. Its general color may be light to dark gray or gray brown with 34–50 (average 40) dark brown or black blotches on the back and 3 alternating rows of smaller dark spots along the sides. The head is noticeably wider than the neck, with 9 large scales on the top and 2 dark stripes edged in white along each side of the head. A sensory pit (heat-sensing pit) is located between the nostril and eye on each side of the head. The tail is light with dark bands and is tipped with a distinct rattle. The belly is normally light gray with darker gray mottling, although some individuals will have a mostly black belly in the north-central Missouri populations. Scales along the back are keeled, and the anal plate is single.

This rattlesnake is generally mild mannered and hesitant to strike unless harassed. When approached, massasaugas usually remain motionless to avoid detection or quickly seek shelter in thick vegetation or crayfish burrows. However, this small rattlesnake will become defensive, sound its rattle, and strike when cornered or harassed.

Similar species:

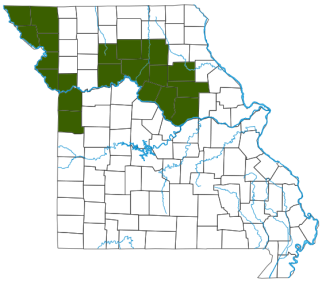

- The eastern massasauga (S. catenatus) is extremely similar, but it has not been seen in Missouri for many decades and is considered extirpated. Within our state, the two massasaugas are mainly identified based on geographical range: the prairie massasauga occurs in our northwestern corner and in some north-central counties, while the apparently extirpated eastern massasauga occurred along the Mississippi River floodplain north from St. Louis. The last confirmed report of the eastern massasauga in Missouri dates to 1941, so the species is likely extirpated from the state. But Missourians should keep a watchful eye for this secretive species, which is federally listed as threatened throughout its range. If an individual is observed, photograph it and report it to the Missouri Department of Conservation.

- Two other rattlesnakes are known from Missouri, and they are not as rare as massasaugas. The timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) occurs statewide and is the only other rattlesnake you will likely find in north Missouri. Adults of that species are about 3–5 feet long. In addition to being much larger, the timber rattlesnake has a rusty stripe down its back. The western pygmy rattlesnake (Sistrurus miliarius streckeri) rarely exceeds 20 inches in length and is not found in northern Missouri. It lives in counties bordering Arkansas and in the eastern Missouri Ozarks.

Length: 18–30 inches. The largest individuals can potentially reach 35 inches.

Isolated populations survive in some north-central counties and in the northwestern corner of the state.

Habitat and Conservation

In Missouri, massasaugas are restricted to marshes or moist prairie habitats located within or near large river floodplains or scattered moist prairie swales within upland grassland habitats. Due to extensive habitat loss, the range of this species has been reduced to a few isolated areas in north-central and northwestern Missouri.

Prairie massasaugas spend considerable time basking during sunny, warm days in an open space among vegetation, coiled on top of a crayfish burrow or ant mound, or sometimes on top of matted vegetation several feet above ground.

In Missouri, this species overwinters primarily in crayfish burrows and ant mounds, although other animal burrows can be used. Most individuals rely on crayfish burrows that reach groundwater below the frost line. Often massasaugas will move from moist prairie habitats after emergence to drier upland sites.

Protection and management of bottomland prairies is vital to sustaining this Missouri endangered species: It is mainly found in bottomland or wet prairies dominated by cordgrass, sedges, bullrushes, and smartweeds, and lowlands by rivers, lakes, and marshes. They prefer places where there are numerous crayfish burrows providing shelter from predators and weather conditions. They require wetlands associated with river floodplains of north Missouri. Populations have declined because of habitat loss as wetlands were drained and floodplains and prairie were converted to farmland. Restoring wetlands along rivers, improving existing wetlands, and protecting this snake from being killed are the keys to the survival of this species.

Food

In Missouri, massasaguas feed primarily upon rodents (especially voles and mice). Young massasaguas also eat other types of snakes, including brownsnakes and gartersnakes.

Status

The prairie massasauga is a species of conservation concern, listed as endangered in Missouri due to few populations, low numbers, and greatly reduced natural bottomland prairie habitat. The prairie massasauga once occurred in large numbers across much of north-central and northwestern Missouri. Five isolated populations are currently known in the state.

Missouri populations of prairie massasaugas may be genetically distinct and deserve continued protection. If an individual massasauga is located, photograph and report it to the Missouri Department of Conservation.

Missouri's two massasauga species formerly were considered two subspecies of "eastern massasauga" (Sistrurus catenatus), but they have been split into separate species. The massasauga population discussed on this page is now considered a subspecies of western massasauga (S. tergeminus) that is called the prairie massasauga (S. tergeminus tergeminus). Meanwhile, the eastern massasauga (S. catenatus), a candidate for federal endangered status, is likely extirpated from Missouri. It used to occur along the Mississippi River floodplain north of St. Louis.

Both of Missouri's massasauga species are listed as endangered in our state. None can be injured, killed, or taken from the wild for any use.

Human deaths caused by massasauga bites are rare, but studies show that the their venom is highly toxic, so these snakes must be respected and classified as dangerous.

Life Cycle

This species is mostly active from April through October, but surface activity can occur in March and into November if temperatures are warm enough.

They are primarily diurnal, especially in April and May, and again in October, but during the heat of summer they become more nocturnal.

Courtship and mating may occur in spring or autumn in Missouri; apparently Missouri populations mainly mate after spring emergence. Females give birth to an average of 6 or 7 live young; larger females produce larger litters. With favorable weather and abundant prey, females may reproduce annually; otherwise, they may reproduce every other year. Most births take place in August and September. Newborns are 8–11 inches long and have a lighter ground color and darker blotches than adults; also, they have a yellow tail tip and a single rattle button. They reach sexual maturity in their second, third, or fourth year of life and may live to be at least 20 years old.

Human Connections

Many of us fear rattlesnakes, but as we increase our understanding of how these snakes fit into the balance of nature, our knowledge and appreciation of these disappearing snakes makes us concerned for their survival.

Massasauga is a Native American word meaning “great river mouth”; it refers to the wet, lowland habitats associated with this snake along rivers.

Missouri's venomous snakes are dangerous to people and should be avoided. Even freshly killed specimens can inflict a dangerous bite due to reflex action. A local or regional American Red Cross office can furnish up-to-date information on venomous snakebite first aid. In the event of a snakebite caused by a venomous species, the victim should be transferred to a hospital emergency room as soon as possible. Most bites occur when people are trying to kill or handle venomous snakes.

Accidental bites can be avoided by staying away from areas where there may be a concentration of venomous snakes.

- Wear protective footwear in habitats where dangerous snakes may occur.

- Never place your hands under rocks or logs, and do not step over rocks or logs. Step on them first, then over.

- When walking in a forest, step lively.

- Look the ground over when you stop to stand or sit, particularly around large rocks or logs.

- Pit vipers are most active in late evening and at night; be extra careful during these times.

- Finally, avoid any snake you cannot identify.

Most species of venomous snakes are shy and normally avoid people. When encountered in the wild, they usually try to escape detection by remaining motionless. Often, an individual that is provoked will try to escape rather than defend itself. Once cornered, however, these snakes will do their best to defend themselves. Learning to distinguish venomous from nonvenomous species by their color and pattern is recommended.

Ecosystem Connections

Massasaugas hunt voles, mice, and other rodents, plus smaller snakes, keeping their populations in check. As a resident of marshy areas and moist prairies, this efficient predator thus has an important predatory niche within those habitats.

Rattlesnakes are considered the most evolutionarily advanced group of snakes. In addition to hollow fangs and heat-detecting facial pits, their tail rattles warn would-be predators not to attack them, saving the snake from having to bite and the enemy from being bitten. But rattlesnakes are often preyed upon by hawks, kingsnakes, and other predators.