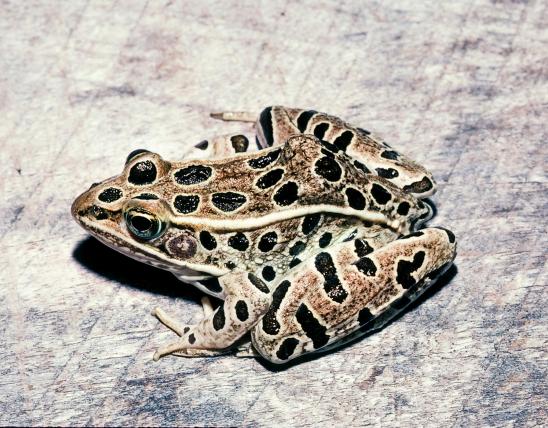

The pickerel frog is a medium-sized frog with a wide ridge of skin (dorsolateral fold) along each side of the back, and two parallel rows of squarish or rectangular spots running down the back between the folds. The general color is gray, tan, or brown. A white line is present along the upper lip. The distinct dorsolateral fold extends down to the groin and may be white, cream, gray, yellow, or gold. The spots on the back are reddish brown, dark brown, or black. Dark bars on the hind legs are prominent. The undersides of the hind legs and groin area are washed with bright yellow, orange yellow, or pink yellow. The belly is white.

The call of male pickerel frogs is a low-pitched, descending snore lasting a couple of seconds. Although this frog usually calls from above water like most other frogs and toads, it may also call while under water.

Similar species: Missouri’s three species of leopard frogs lack the pickerel frog's combination of having wide, unbroken skin folds along the back; two distinct rows of square or rectangular spots down the back; and yellow or orange-yellow coloration along the undersides of the hind legs and groin area.

Missouri has eight members of the true frog family. These are typically medium to large frogs with long legs, smooth skin, and well-developed webbing between the hind toes. Another common characteristic is a glandular fold or ridge of skin along each side of the back (these are called dorsolateral folds).

Adult length (snout to vent): 1¾ to 3 inches; occasionally to 3½ inches. Adult males are generally smaller than adult females.

Common in southern and eastern Missouri. Absent from the northwestern third.

Habitat and Conservation

The pickerel frog is associated with springs, cold streams, and cool, shaded woodland ponds. In Missouri, it occurs along Ozark streams under rocks at the water’s edge. Pickerel frogs also live along streams in grassy areas, pastures, and near farm ponds, along shaded ravines in forests, in moist grassy fens, and under rocks on glades during the spring. In eastern Missouri along the Mississippi River, this species lives in and near springs and creeks that flow from limestone bluffs. In central Missouri during the hot summertime, people often see this frog in and around wet areas of yards, gardens, and water fountains.

Pickerel frogs are especially associated with caves and cave entrances. They use aquatic caves as a refuge from late summer's heat and winter's cold. This is the only frog in Missouri that shelters in caves with regularity and in high numbers; a single cave may harbor hundreds of pickerel frogs.

During March or early April, the frogs leave the caves and move to a woodland pond, slough, or water-filled ditch for breeding. They feed during spring and summer, then they start returning to the cave in late July.

In addition to overwintering relatively deep inside wet caves, pickerel frogs may also overwinter in springs, in mud at the bottom of streams or ponds, and under large stones along the banks of small streams.

Even though pickerel frogs are especially known for living in the somewhat specialized habitats of cool springs, streams, and caves, they appear to be common throughout the Ozark region's karst, forested habitats.

Food

Pickerel frogs eat a variety of invertebrates, including ants, spiders, beetles, moth caterpillars, sowbugs, crickets, and earthworms.

Status

Taxonomy: The true frog family (Ranidae) is the largest and most widespread family of frogs. It contains 365 species in 14 genera and probably originated in Africa. Representatives of this cosmopolitan family occur on every major land mass except New Zealand, Antarctica, most oceanic islands, the West Indies, and southern South America. The largest genus in the family in the New World (North and South America) is Lithobates (formerly Rana), with about 50 species. Missouri’s species, formerly in genus Rana, are all in genus Lithobates. As of taxonomic understandings in 2016, the Rana genus is considered restricted to the eastern hemisphere and western North America. In Missouri, the genus Lithobates is represented by eight species.

Life Cycle

Breeding occurs March through May, in woodland ponds, sloughs, and water-filled ditches. Peak chorusing is from mid-April to early May. Females lay 700–2,900 eggs in shallow water in a globular mass attached to a submerged stick or stem. The tadpoles hatch in 10 days or more, and they transform into froglets after 3½–4 months. The transformation is complete around mid-July to mid-August. Development time varies with temperature.

Human Connections

Frogs help control populations of sometimes-troublesome insects. Because they are sensitive to pollutants, they are considered indicator species whose health and numbers can be a way to gauge the health of their ecosystem.

Pickerel frogs, as a defense against predation, emit a toxic secretion from their skin when threatened. Some people may experience skin irritation after handling these frogs.

Caves are delicate ecosystems, and to protect the many species that live in them, it is recommended that people refrain from entering caves. Also, teach yourself about groundwater ecology, groundwater and runoff pollution, and learn ways to protect caves, springs, sinkholes, and other underground habitats.

The species name, palustris, means "of the marsh," referring to one of the habitats of this widespread species. The common name, "pickerel," might refer to the rows of squarish spots, which are a little reminiscent of the organized markings on the sides of some species of pickerel fish. Another theory is that pickerel frogs might have been used as bait by people fishing for pickerel.

Ecosystem Connections

Frogs are predators that help keep populations of insects and other small animals in balance. They, and especially their eggs, tadpoles, and young froglets, can become food for larger predators, including bullfrogs and green frogs, watersnakes and gartersnakes, and birds such as herons.

But pickerel frogs emit skin secretions that are irritating or even toxic to small animals. If newly captured pickerel frogs are placed in the same container with other types of frogs, the latter will die within a short time due to these skin secretions. These secretions appear to be a defense against predation. Many frog-eating snakes will not eat pickerel frogs. A study in Kentucky showed that pickerel frogs that breed in ponds where fish are present are likely to be more toxic than frogs that breed in fishless ponds.