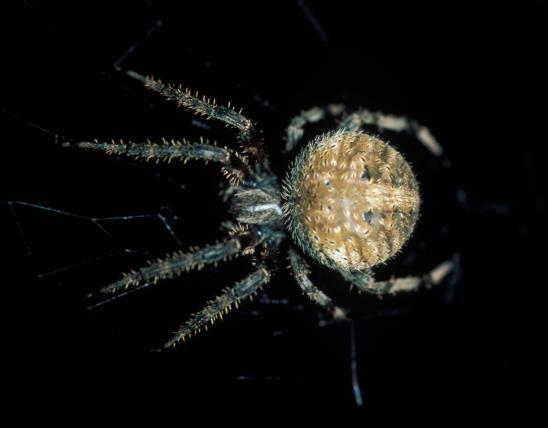

The first impression of a featherlegged orbweaver is of a small oval blob with a tiny, curved “twig” protruding from one end (when the forelegs are held together), or of a tiny V-shaped twig (when the forelegs are held apart). The general colors of this small, hairy spider are drab: white, yellow, gray, tan, brown, or black, and the camouflage pattern varied. The abdomen is arched, with the highest point of the hump toward the front of the abdomen and having two moundlike tubercles, one on each side. Females have conspicuous brushlike plumes of hair on the tibia segment of the elongated, heavier first pair of legs.

This species belongs to a family of spiders called the cribellate orbweavers (Uloboridae). This family is unique in North America because its members completely lack venom. And what does “cribellate” mean? A cribellum is a sievelike plate associated with the spinnerets (the organs where the silk comes out). The cribellum causes the silk that emerges from the spinnerets to be “hackled,” or covered with woolly fibers that help snag prey (instead of the sticky threads many other spiders use).

Although a number of spider families include at least some species that are cribellate, this particular cribellate family is unusual because its members spin orb (wheel-shaped) webs. Cribellate spiders are not closely related to the true orbweavers, family Araneidae, and most spider families that possess a cribellum do not create circular orbs.

So the featherlegged orbweaver, with other members of its family, is an oddity: it lacks venom, it produces woolly threads instead of sticky ones, and it spins orb webs.

The egg sacs of this species are elongated on one end, slightly spiraled, and have minute spines; they resemble the shape of a whelk shell. Females create linear chains of these egg sacs and typically rest at one end of the chain, forelegs outstretched, looking like just another segment of the chain; the whole impression is of a line of detritus. Also, this species often spins stabilimenta (silken ribbons forming zigzags, lines, or spirals) in the web.

Similar species: There are many other members of genus Uloborus, but most of them live in the tropics. This is the only common member of its genus in our region. Trashline orbweavers (genus Cyclosa, in the true orbweaver family) hide in their orb webs amid a vertical line made of detritus (empty husks of prey insects), with the egg sacs positioned at the hub. The abdomen of trashline orbweavers is typically conical, pointed upward (not downward) at the tip, which extends well past the spinnerets.

Length (not counting legs): females can be ⅛–¼ inch; males slightly smaller.

Statewide.

Habitat and Conservation

The featherlegged orbweaver creates circular (orb) webs that lack sticky threads. Instead, woolly fuzz on the strands composing the spiral part of the web ensnares prey. The webs are usually seen in low shrubs and other vegetation, about knee-high.

Food

Featherlegged spiders eat small flies, such as mosquitoes, and other small insects, capturing them in their fuzzy-stranded webs. This spider lacks venom! After wrapping its captive in silk, the spider regurgitates digestive juices onto the victim and ingests the prey as it liquefies.

Status

Common, but easily overlooked.

Life Cycle

The egg cases of this spider are shaped like whelk shells — spindle-shaped but with one end longer-pointed than the other, coiled-looking, with minute spines on the blunter end. Uninterrupted chains of these egg sacs are created in a straight line across the web. The female featherlegged orbweaver rests at the end of the line, forelegs outstretched and pressed together, making her appear as a link in the chain. Like most other spiders, a female can create multiple egg sacs from a single mating. Also like most spiders in our climate, the adults die upon the first freezes of winter, and spiderlings hatch out in spring.

Human Connections

How can anyone be unhappy with a mosquito-eating spider that completely lacks venom? One of the great wonders of nature is the tremendous diversity of predators and prey within each ecosystem. Perhaps you’ve never heard of a featherlegged spider, but they are part of a staggering number of small predators that keep in check the hordes of mosquitoes and other insects that vex us.

Ecosystem Connections

Predatory insects typically play two roles in the order of nature: predators of smaller insects, but also vulnerable to predation themselves. Many kinds of animals — birds, toads, frogs, lizards, small snakes, shrews, and even rodents — are some clear reasons for this spider’s camouflage coloration and behavior.