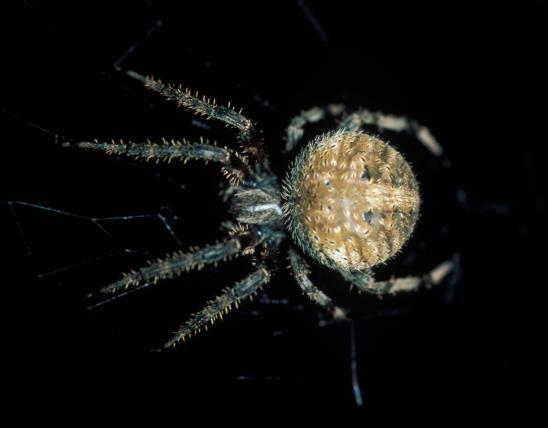

The webs of trashline orbweavers are more conspicuous than the spiders themselves. The webs are small, circular orbs that the spider “decorates” with a line of debris: the dry husks of insects it has eaten plus other bits of detritus, wrapped loosely with silk into usually a straight line. The tiny, well-camouflaged spider typically rests in the center of her “trash line,” almost always at the hub of the web. With her legs tucked in, her upward-pointed abdomen blends in with the debris. The egg sacs are also positioned among the trash. Color and patterning of this species are cryptic: tans, grays, or browns, with some individuals with white, black, yellow, or rusty red.

Five species of Cyclosa occur in North America north of Mexico, but only Cyclosa conica and C. turbinata are found in Missouri. They can be separated by the latter’s being smaller and having two humps on the fore part of the top of the abdomen (the humps are sometimes described as looking like “shoulders”). These diagnostic humps can sometimes be indistinct.

Similar species: Featherlegged orbweavers (Uloborus glomosus) also make blobby lines in their orb webs, but in their case, the blobs are all egg cases, while the trashline orbweaver’s blobs are mostly insect carcasses. Looking at the spiders more closely, the abdomen of trashline orbweavers points upward at the hind end, while those of featherlegged spiders points downward. Also, the first pair of legs of featherlegged spiders are remarkably long.

Length (not counting legs): females can be ⅛ to about ¼ inch; males about ⅛ inch.

Statewide.

Habitat and Conservation

Trashline orbweavers live in a variety of wooded habitats, including parks and yards, usually in low vegetation up to about 6 feet in height. At a glance, the trashlines of these spiders look like a bird dropping that hit then ran down the spider web, making it look derelict and old. Some species of trashline orbweavers will vibrate or jiggle their body when disturbed, becoming a blur and difficult to see.

Food

These small spiders eat a variety of small flying insects, such as mosquitoes, midges, moths, small beetles and bugs, and houseflies.

Status

Missouri’s two species of trashline orbweavers are widespread and common throughout much of the United States, yet neither has its own common name. By simply translating the Latin species names, C. conica could easily be called the cone-shaped (or conical) trashline orbweaver, and C. turbinata the top-shaped trashline orbweaver.

Life Cycle

The egg cases of trashline orbweavers are positioned in the string of detritus and are therefore hidden just like the mother. Like many other spiders in our temperate climate, the adults usually all die in the first freezes of late fall, and young spiderlings hatch from their eggs in spring. To disperse, these and many other types of young spiders climb to the top of some object, wait for a breeze, let out a loop of silk, and jump — the breeze carries them away from their siblings. This is called “ballooning.”

Human Connections

Humans have a tendency to see ourselves in animals — to attribute to them human personalities, motivations, or other characteristics. Biologists caution against this tendency, and in their studies they carefully avoid projecting human traits on animals. But in folklore, literature, and even religion, animals are often portrayed as little people (think of Aesop's fables). In a fanciful view, trashline orbweavers might be imagined as habitual “hoarders” who preserve old fast-food containers, chicken bones, and other remnants of former meals around the home.

Ecosystem Connections

The trashlines of these orbweavers almost certainly function as a form of camouflage, allowing the spider to evade its predators. It reminds us that spiders usually have a dual role in ecosystems: predators to small insects, but prey themselves to other animals.

At first glance, the trashlines of these spiders look bird droppings that have run down the web and then dried, making it look derelict and old. This would put these spiders into the same category as several types of butterflies and moths, whose caterpillars also resemble bird droppings. In each case, this camouflage tells potential predators: “Move along; nothing to see here.”