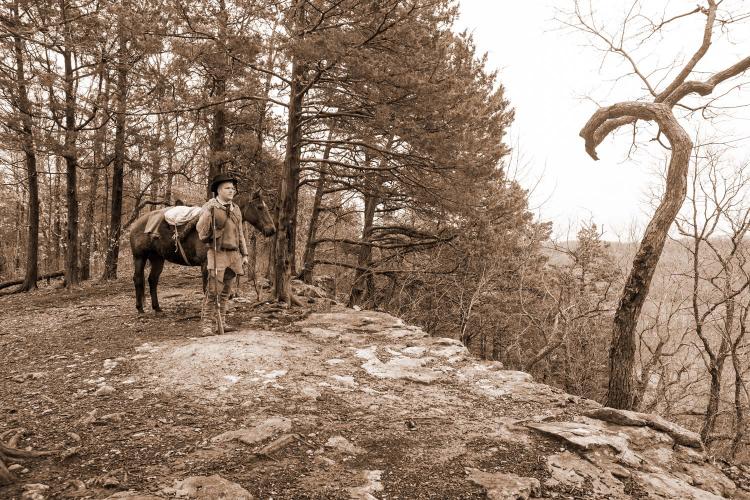

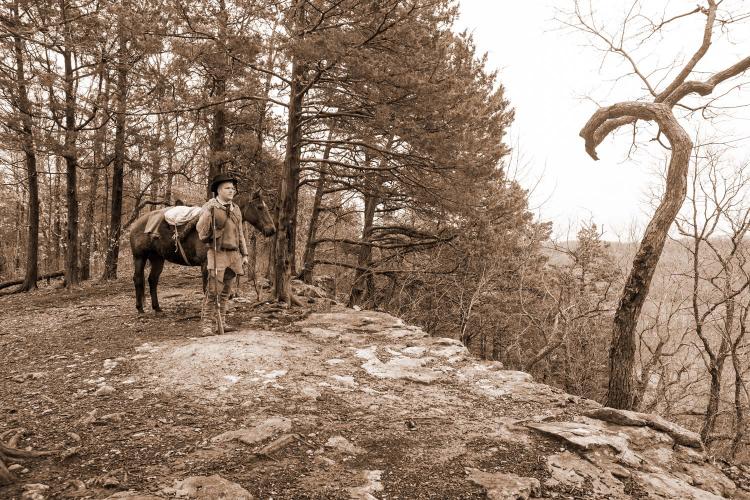

“I begin my tour where other travelers have ended theirs, on the confines of the wilderness.”

Two centuries after they were written, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s words still beckon outdoor enthusiasts to southern Missouri.

On Nov. 6, 1818, Schoolcraft, his friend Levi Pettibone, and one pack horse left Mine á Breton (present-day Potosi) in the Missouri Territory. They were on a quest to learn more about the mining potential of lead deposits on the James River in the southwest part of the territory.

What followed was a 900-mile, three-month odyssey into what is now southern Missouri and northern Arkansas. Schoolcraft found lead near present-day Springfield, but a more valuable resource he provided was the detailed journal he kept of his travels. Published in 1821 under the nondescript title Journal of a Tour into the Interior of Missouri and Arkansas in 1818 and 1819, this was the earliest description of the interior Ozarks by a skilled observer. Schoolcraft’s notes on wildlife, vegetation, and landforms provide baseline knowledge about what this part of Missouri looked like two centuries ago.

Today, Schoolcraft’s entries entice hikers, hunters, floaters, and anglers who want to envision what the pre-settlement Ozarks were like.

Potosi to the Huzzah

Your journey, just like Schoolcraft’s, begins in Washington County at Potosi — although you’ll likely travel by motorized vehicle instead of by foot with a packhorse in tow. Head west on Missouri Highway 8, cross Courtois and Huzzah creeks. One of Schoolcraft’s early campsites (Nov. 8, 1818) was near MDC’s Huzzah Conservation Area in Crawford County. This 6,225-acre area is known for floating, fishing, hunting, and hiking opportunities, both on MDC-managed trails and on a stretch of the Ozark Trail, managed by the Ozark Trail Association, that crosses the site.

Schoolcraft’s general route goes through Steelville, south on Missouri Highway 19 into Dent County and near a unique natural feature — glades. Glades are hot, dry openings within woodlands that are noted for shallow and/ or poor soils and exposed bedrock.

“Glades are beautiful communities that support a diversity of sun-loving plants and animals,” said John George, MDC’s wildlife supervisor for the central region. “Despite their beauty they can be best described as hard rocky deserts to those who were working to carve out a living in the Ozarks.”

Big Glade Natural Area, which lies within MDC’s 13,310-acre Indian Trail Conservation Area in Dent County, is one place to visit these unique habitats. Visitors in summer may see colorful wildflowers such as white and purple prairie clover and pale purple coneflower.

Meramec to the Current

Schoolcraft’s route heads south on Highway 19 and across the Meramec River. He made frequent mentions of elk between the Meramec and Current Rivers. Today, elk are found in the MDC Elk Restoration Zone in Shannon, Reynolds, and Carter counties. Good places to see elk are the 23,049-acre Peck Ranch Conservation Area and the 29,331-acre Current River Conservation Area. Both MDC areas are near Ellington and stretch into Shannon, Reynolds, and Carter counties. Take the self-guided elk driving tour at Peck Ranch or hike the Ozark Trail near Peck Ranch’s headquarters in early October and listen for a bull elk’s bugling. In winter, look for elk feeding in food plots along Peck Ranch’s main valley road.

Schoolcraft left the Salem Plateau’s prairies and open woodlands and entered the Current River valley, noting “the waters of this stream are very clear and pure, and ducks are common upon it. The wild turkey and squirrel are also seen on its banks.” (Nov. 11, 1818) People can still find many outdoor activities in Current River country. Hunting, fishing, camping, and hiking are popular. Seeing the river from a canoe or kayak is preferred by many. Several agencies manage parts of this area for public recreation. The National Park Service manages the Ozark National Scenic Riverways, which covers 134 miles of the Current and Jacks Fork rivers. The Missouri Department of Natural Resources manages Montauk State Park at the headwaters of the Current River and near where Schoolcraft crossed the Current.

From Current River to the North Fork of the White

Schoolcraft’s general route continues south from Salem on Missouri Highway 32 toward Licking, then south on Missouri Highway 137. At Raymondville, turn west on Texas County Highway B toward Houston. West of U.S.Highway 63, this route passes by a gem of Missouri’s natural area system — the Piney River Narrows Natural Area in Texas County. This 50-acre area is highlighted by large dolomite outcroppings.

Schoolcraft saw black bears several times on his journey. By the end of the century, bears were almost extirpated from the state. Fast forward to 2018 and Missouri’s black bear population is recovering. MDC biologists attribute this increase primarily to a resurgence of large forested habitats in the Missouri Ozarks. On Nov. 17, 1818, a few miles north of present-day Cabool, Schoolcraft and Pettibone had a memorable bear encounter.

“We had not travelled far when we discovered, in a ravine below, four bears upon trees. We have not heretofore sought to go out of our way for the purpose of hunting, but this was directly in our course, and too fine an opportunity to exercise our skill in hunter sport to be neglected. We determined to give them battle.” (Schoolcraft, Nov. 17, 1818)

Schoolcraft and Pettibone approached cautiously, but the bears saw them and began to descend the trees and flee. Schoolcraft fired his gun when the last bear reached the ground, but this had no effect on the animal, which scampered away. The lost opportunity of much-needed meat was compounded by a badly sprained ankle that Pettibone suffered. However, the two traveled 18 miles the next day, with Pettibone riding atop the packhorse and supplies.

Down the North Fork of the White

Schoolcraft and Pettibone spent 13 days winding down the North Fork of the White. While visiting one of the river’s many springs, Schoolcraft wrote, “the waters possessing the purity of crystal. I set my gun against a tree, and unbuckled my belt, preparatory to a drink, and in taking a few steps toward the brink of the spring, discovered an elk’s horn of most astonishing size, which I afterwards hung upon a limb of a contiguous oak, to advertise (to) the future traveler that he had been preceded by human footsteps in his visit to the Elkhorn spring.” (Nov. 20, 1818)

The North Fork flows through some of the most scenic and rugged country in Missouri, as well as 22,000 acres of Norfork Lake known for its walleye and bass fishing. Cold, clear spring water that emerges along the river’s course makes the North Fork one of the nation’s premier trout streams. Today, Schoolcraft would want to pack fishing gear to use at MDC’s designated Blue Ribbon and Red Ribbon trout fishing zones of the river. The Blue Ribbon Zone begins at the upper outlet of Rainbow Springs and extends downstream 8.6 miles to Patrick Bridge. For fishing regulations, visit huntfish.mdc.mo.gov/fishing.

Schoolcraft’s route narrowly missed a spot popular with today’s hikers and campers — the Devil’s Backbone Wilderness Area. This 6,687-acre U.S. Forest Service area in Ozark County is named for a long narrow ridge bordering the North Fork River and contains 13 miles of moderate hiking trails. Learn more about this area at fs.fed.us.

Finding Lead, Heading Home

Southern Missouri wasn’t totally devoid of white settlement, a fact evidenced by Schoolcraft and Pettibone. Local settlers William Holt and James Fisher guided them on the western part of their journey to what today is the commercially operated Smallin Civil War Cave in Christian County near Ozark. It’s easy to see Schoolcraft’s mouth agape as he tried to describe the cave’s 55-foot tall, 100-foot wide entrance.

“The first appearance of this stupendous cavern struck us with astonishment, succeeded by curiosity to explore its hidden recesses … the number and variety of curious and interesting objects it presents is well worth a day’s attention. To explore it, a boat would be necessary… ” (Jan. 1, 1819)

Two centuries have not changed the awe Smallin Cave creates amongst its visitors.

“It is truly an amazing sight,” said Jackie Hawks, one of Smallin Cave’s guides. “When I take visitors to the cave, several of Schoolcraft’s quotes come to mind. People today are just as amazed as Schoolcraft was 200 years ago.”

Smallin owners Kevin and Wanetta Bright have embraced the site’s connection to Schoolcraft through signage and interpretive tours given at the cave. Special events are planned throughout the site in 2018–2019 to commemorate the bicentennial of Schoolcraft’s visit.

“Schoolcraft’s journey through the Ozarks is important for several reasons,” said Kevin Bright. “He walked on this property, through this valley, and into this cave. Schoolcraft shared the beauty of the Ozarks, the geology, the geography and the people — including the Osage — with the rest of the United States. With Schoolcraft’s account, when our guests and school groups visit the site, we can describe and interpret the land as he saw it and compare it to what is here today.”

A must-read for those interested in retracing Schoolcraft’s trek is Rude Pursuits and Rugged Peaks: Schoolcraft’s Ozark Journal 1818-1819 (University of Arkansas Press, 1996) by deceased Missouri State University history professor Milton D. Rafferty. This book matches 19th century journal entries with 21st century locations and creates a route that beckons the outdoor adventurer. To explore an interactive map of Schoolcraft’s route, visit https://gis.bransonmo.gov/schoolcraft_3 prepared by Curtis Copeland, Geographic Information Systems Coordinator for the City of Branson, Missouri.

Smallin Cave

With Holt and Fisher’s guidance, Schoolcraft reached his objective Jan. 2–4, 1819, when the party found lead ore at the juncture of Pearson Creek and the James River, a site just outside of modern Springfield’s eastern city limits in Greene County. The value of his journal is again driven home in his description of the area that is today south Springfield.

“The prairies, which commence at the distance of a mile west of this river, are the most extensive, rich and beautiful of any which I have ever seen west of the Mississippi River. They are covered by a coarse wild grass which attains so great a height that it completely hides a man on horseback in riding through it. The deer and elk abound in this quarter and the buffalo is occasionally seen in droves upon the prairie …” (Jan. 4, 1819)

Today, this landscape is filled with businesses, schools, and urban residences. Therein lies the value of Schoolcraft’s journal.

“Habitat management requires some type of baseline management,” said Rudy Martinez, Springfield Conservation Nature Center manager. “Having historic records of the native habitat that includes descriptions of plant and wildlife diversity helps land managers identify the historic range of natural viability. Information from Schoolcraft’s journal was — and still is — used to identify the historic range of natural communities found in the Ozarks.”

From this point, Schoolcraft returned along an easterly route that took him through northern Arkansas, back up into southeast Missouri and eventually home to Mine á Breton in eastern Missouri.

The publication of his journal two years later led to federal government work for Schoolcraft, but in historical hindsight, the publication’s true worth is how it benefited the subject, not the author.

“Schoolcraft’s journal is a marker in time, a milepost in not only our state’s historical journey, but in the historical timeline of the United States,” Kevin Bright said. “When the Louisiana Purchase was added in 1803, the Ozarks was unexplored and unknown. Schoolcraft’s journal began the story for this part of Missouri.”

Also In This Issue

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Associate Editor - Bonnie Chasteen

Staff Writer - Larry Archer

Staff Writer - Heather Feeler

Staff Writer - Kristie Hilgedick

Staff Writer - Joe Jerek

Creative Director - Stephanie Thurber

Art Director - Cliff White

Designer - Les Fortenberry

Designer - Marci Porter

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Circulation - Laura Scheuler