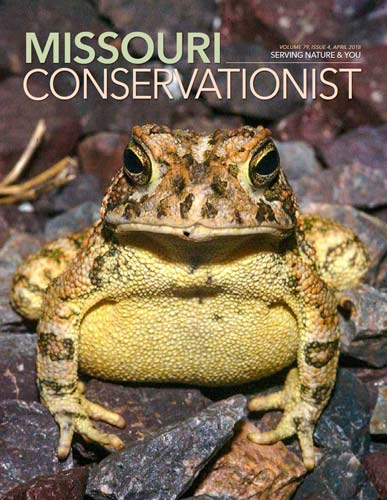

There’s a lot more to these shy, fabled creatures than meets the eye.

While you might be excited to encounter a toad in your yard or the Missouri wilds, some people find the small, warty creatures to be a little creepy. In a number of primitive cultures, toads were considered magical. The mildmannered amphibians featured

prominently in South, North, and Meso-American Natives’ creation myths as a beast that succeeded where others failed — in some cases as a frightening, formidable force. In Asian mythology, toads held the secret to immortality, and Europeans in the Middle Ages associated the golden-eyed hoppers with witches and witchcraft.

The truth about toads

According to the National Wildlife Federation, 580 species of toads inhabit every continent but Antarctica, and of the 22 species native to the United States, four make themselves at home in Missouri. Before 2006, when scientists reordered their classification, the state’s four toad species were included in the genus Bufo, but now scientists classify them in the genus Anaxyrus, though this remains controversial with some herpetologists, or scientists who specialize in the study of reptiles and amphibians.

MDC’s Jeff Briggler is Missouri’s herpetologist. As such, he administers and coordinates surveys, research, and regulations as they apply to the state’s amphibians and reptiles. This includes monitoring the health and well-being of the state’s toad populations: the eastern American toad (A. americanus americanus), Fowler’s toad (A. fowleri), the rare Great Plains toad (A. cognatus), and Woodhouse’s toad (A. woodhousii). “Unlike frogs, toads are more adapted for land,” Briggler said. “They have long, slender toes that lack extensive webbing, and their warty skin helps them retain moisture.”

Toads, like other amphibians, do not drink with their mouths. Instead, they absorb moisture from the ground through a pelvic patch and store it in a lymph sac or bladder. The stored fluids are released when the toad becomes frightened, as most anyone who has picked up a toad can attest.

Harmless to humans, toxic to predators

During the day, toads are inactive andburrow underground in sand or soil, also hiding under organic litter, bark, partially buried logs, and rocks. They become active in the evening and during rains. This lack of daytime activity and their color camouflage are two of the toad’s defense mechanisms, along with their ability to puff themselves up to look more fearsome in the eyes of a predator. Toads also have a secret weapon that protects these otherwise harmless creatures from becoming another animal’s meal.

Kidney-shaped paratoid glands located behind toads’ eyes secrete a moderately potent toxin known as bufotoxin. The milky substance irritates the mucous membranes in predators’ mouths and can even cause death if an animal chooses to ignore the irritation and swallows the toad.

Contrary to popular folklore, toads do not cause warts, but because of bufotoxins, it’s a good idea to wash your hands after touching or holding a toad. “Many mammals won’t eat them,” Briggler said. “But raccoons can devastate toad populations when the toads are out calling at night. A raccoon will eat everything but the head, avoiding the bad-tasting paratoid glands, and can consume up to 20 or 30 toads in a night.” Briggler said toads also are a favorite food of hog-nosed snakes. A few other snake species, herons, and hawks also are known to prey on toads.

Friends of farmers and gardeners

Toads’ meal preferences include mosquitoes, ants, spiders, beetles, crickets, and locusts, as well as snails, cutworms, and earthworms — 10,000 or more in one season — making them great allies of farmers and gardeners.

Toads do not have teeth and must swallow prey whole. But toads’ tongues are attached in the front of their mouths where they are of no use in swallowing. This problem is solved by toads blinking their eyes when they snag a meal, which causes their eyeballs to roll into the roof of their mouth, pushing their prey into their throat, a characteristic shared with frogs.

Male toads woo potential mates with a long musical trill generated from an inflated vocal sac. They can sing alone, but in most cases large choruses can be heard at night. On occasion, they have been known to romance toads of other species. Although males are the most vocal, Briggler said even some female toads make chirping sounds when handled.

“Each of the species has a different calling time frame,” he said. “We train volunteers to record calling activities throughout the state. Some toads are restricted to specific parts of the state while others are statewide, and we collect information on population and distribution trends of these species along defined routes.”

They need wetland habitat to breed

The American toad can be found statewide, with one subspecies, A. a. americanus, inhabiting northern Missouri, and a second dwarf species living predominately in the southern half of the state. Both Fowler’s and Woodhouse’s toads typically prefer floodplain areas. Their habitats overlap to some extent, and it can often be difficult to distinguish between these two species. However, Briggler said Fowler’s toads prefer more upland habitat, especially in the Ozark Highlands.

“In Missouri, the Great Plains toad is found only in the Missouri River floodplain from Jefferson City to extreme northwestern corner and is a fairly rare species. We spend more time surveying for them to determine population status and distribution in the state. They are a species of conservation concern, due to limited distribution and habitat loss, but appear to be doing well in Missouri at this time,” Briggler said. “The biggest threat to Missouri toads is loss of habitat, especially temporary wetlands necessary for breeding.

“Toads breed and lay their eggs in wetlands, places like farm ponds, temporary pools, ditches, sewage lagoons, rain gardens, little creeks, and garden ponds,” he said. “They reach sexual maturity in two to three years with males reaching reproductive age before females.”

A female toad lays between 2,000 and 20,000 eggs. And unlike many frogs, which deposit their eggs singly or in masses, toads lay eggs in long strings. Most eggs hatch within a week, and the tiny, black tadpoles develop into toads that are ready to hop onto dry land in six to eight weeks.

“As with many species, there are good reproductive years and bad reproductive years for toads, dictated by weather conditions,” Briggler said. “When a ditch where eggs are laid dries up too quickly, the tadpoles die, but in wet years, many tadpoles survive to move onto land as tiny toads. Even though toads are known to lay thousands of eggs, typically less than 1 percent reach adulthood.”

Fun to observe, important to conserve

In addition to answering questions and tracking amphibian populations, one of the state herpetologist’s duties is to inform people of Missouri’s regulations as they pertain to the collection and possession of amphibians and their eggs. “If you are a Missouri resident, you can have up to five toads in your possession. We want people to be able to possess a few individuals in order to learn about their interesting behaviors, but at the same time to conserve natural populations in the wild,” Briggler said.

For those who want to watch tadpoles develop into toads, Briggler suggests feeding them a diet of cooked lettuce and spinach to keep them healthy as they develop.

“Personally, I encourage kids to keep a toad or two that they catch for a few days and then let them go where they captured them,” Briggler said. “Also,remember that toads, like many other small animals, are fragile and can often be squeezed too hard.

“Toads are popular as pets. They aresmall and relatively easy to maintain.But if you decide to have a toad as a pet,you should not feed it a one-item diet, like purchased worms or crickets. Feed items like grasshoppers, crickets, worms, and other bugs in the yard to build up the nutritional value of their diets,” Briggler said.

Toad lifespans range from five to 12 years in the wild, but there are instances of toads living much longer in captivity. “There’s a great fascination with toads,” Briggler said, acknowledging that part of their popularity is in response to the fact that they are easy to observe. “They were made for land and don’t move too quickly. Some people grow accustomed to seeing that little toad sitting there in the same spot every day.”

A guide to Missouri’s Toads

American toad (Anaxyrus americanus americanus)

Missouri range: Exists throughout the state; prefers rocky, wooded areas at forest edges

Size: 2 to 3 inches; females typically larger than males

Identifying characteristics

- Gray, light brown, or reddish-brown

- Dark spots on back may encircle from one to three warts

- Belly is cream-colored and mottled with dark gray

Sound: High-pitched musical trill lasting six to 30 seconds

Breeding: Late March, April, and early May

Fowler’s toad (Anaxyrus fowleri)

Missouri range: Found along many Ozark streams in most eastern and southern parts of the state on gravel bars and in sandy soil

Size: 2.5 to 4 inches

Identifying characteristics

- Gray, tan, brown, or greenish-gray color with paired dark markings, each with three or more warts

- Often a thin, white stripe down the back

- Belly is cream-colored

- May be a dark gray spot on the chest

Sound: Short nasal ”w-a-a-a-h” lasting from one to 2.5 seconds

Breeding: Late April to early June

Great Plains toad (Anaxyrus cognatus)

Missouri range: Floodplain of the Missouri River from central Missouri to the northwestern corner of the state; rare

Size: 2 to 3 inches; females larger than males

Identifying characteristics

- Skin covered with many small warts

- Large, dark brown, or green, paired blotches encircled by contrasting white or tan lines

- Cream-colored belly

- Exhibits a raised hump (known as a boss) between its eyes

Sound: Loud, rapid piercing, metallic, chugging “chee-ga, chee-ga, chee-ga” that lasts 20–50 seconds

Breeding: Mid-March to early June

Woodhouse’s toad (Anaxyrus woodhousii)

Missouri range: Mainly along the Missouri River floodplain and along streams in the western part of the state

Size: 2.5 to 4 inches, occasionally larger

Identifying characteristics

- Extremely variable — gray, greenish-gray, and tannishgray to brown

- Irregular dark markings with the number of warts in each varying from one to six

- White stripe often present down back

- White belly

Sound: Short, nasal “w-a-a-ah” lasting from one to 2.5 seconds

Breeding: April to June

Also In This Issue

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Associate Editor - Bonnie Chasteen

Staff Writer - Larry Archer

Staff Writer - Heather Feeler

Staff Writer - Kristie Hilgedick

Staff Writer - Joe Jerek

Creative Director - Stephanie Thurber

Art Director - Cliff White

Designer - Les Fortenberry

Designer - Marci Porter

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Circulation - Laura Scheuler