The small-mouthed salamander is medium-sized, with a small head and mouth. It is usually dark gray to black or dark brown. the body, limbs, and tail may be mottled with small, irregular flecks of tan, grayish blue, or gray. The belly is usually dark gray to black, but small flecks may be present. There are 13–15 costal grooves (vertical grooves on the sides of the body).

Similar species: This is one of six Missouri species of mole salamanders (family Ambystomatidae); all six are in genus Ambystoma. This one is distinguished by its relatively small head, overall dark coloration with small tan or grayish flecks, and range within the state. The species most likely to be confused with it is the mole salamander (A. talpoideum), which has a proportionately larger head, grayish flecks (but not tan), and the fact that in our state it occurs only in the southeastern corner.

Adult length: usually 4–5½ inches; occasionally to 7½ inches.

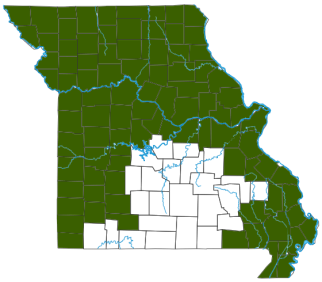

Found throughout much of Missouri except for most of the Ozark Highlands.

Habitat and Conservation

Small-mouthed salamanders live under rocks, rotten logs, and piles of dead leaves, or in burrows in the soil. They typically live in bottomland and floodplain forests, but they also occur on rocky hillsides, woodlands, prairies, and even farmland. They sometimes live in mole burrows and crayfish burrows.

The small-mouthed salamander is likely common throughout much of its range but is rarely seen. Keeping this species common in Missouri depends on protection and construction of temporary, fishless wetlands within the overall natural habitat.

Food

Earthworms, slugs, moths, centipedes, beetles, and insects.

Status

Apparently common in much of its range, but it is hard to study because it is so secretive. Habitat destruction has no doubt caused this species to disappear locally.

Life Cycle

Breeding occurs from late February to early April. Small-mouthed salamanders emerge from underground wintering locations on rainy nights and migrate in large numbers to fishless wetlands.

Breeding locations may include both woodlands and grasslands, but the preferred breeding habitats are shallow, temporary wetlands such as pools, roadside ditches, and flooded fields. They may also breed in more permanent wetlands, such as farm ponds, borrow pits, and swamps. They may even deposit eggs on twigs or at the bottom of sluggish headwater streams.

Females lay eggs singly, in small, loose clusters, or in sausage-shaped masses of 6–30 eggs. These are attached to submerged twigs or plant material. Eggs take 2–8 weeks to hatch into gilled, pond-type larvae. The larvae remain in the wetland for 2–4 months. They typically move onto land from late May through July.

Human Connections

For most of us, finding a salamander is not an everyday occurrence. When we see an unusual animal, we tend to take pictures of it, post them on our social media pages, and try to learn its name and other facts about it. There is an inherent pleasure in learning about the natural world.

Ecosystem Connections

As predators, small-mouthed salamanders help to limit populations of worms, slugs, and insects.

As prey, they and their eggs and young feed a variety of snakes, mammals, and other creatures. When threatened by a predator, a small-mouthed salamander may exhibit defensive posturing, curling its body, raising and waving its tail, and exuding a sticky, white, noxious secretion.

These and other mole salamanders benefit from moles, crayfish, and other animals that dig burrows the salamanders later occupy.