The red-bellied snake is a small woodland species. It is gray or reddish brown, normally with 4 narrow, dark stripes, a faint light stripe along the middle of the back, or some combination of this striping. Some individuals may have a distinct, even bold, red or orange stripe running along the back; this stripe may be rather wide. The head is usually darker than the body, and the nape of the neck has 3 light spots, which occasionally fuse to form a tan collar mark behind the head. The belly is orange, red, pink or occasionally yellow.

Similar species:

- The red-bellied snake is a close relative of Dekay's brownsnake.

- The red-bellied snake used to be divided into several subspecies, including the northern red-bellied snake (Storeria occipitomaculata occipitomaculata). Subspecies are no longer recognized within this species.

- The red-bellied snake is sometimes mistaken for a young copperhead and killed because of unwarranted fear. Copperheads, however, are stout-bodied and have hourglass-shaped markings on the back, vertical pupils in the eyes, a sensory pit between each nostril and eye, and, sometimes, especially in young copperheads, a yellow tail tip.

Adult length: 8 to 10 inches; occasionally to 16 inches.

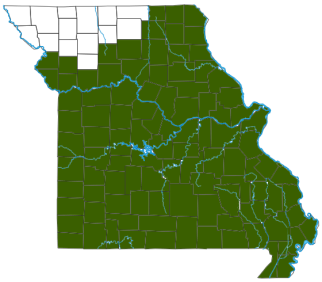

Nearly statewide, but apparently absent from the northwestern and southeastern corners.

Habitat and Conservation

Active from late March through early November, the red-bellied snake is secretive and spends most of its time hiding under rocks, boards, scattered tree bark, logs, and other objects. Sometimes it basks in the sun.

The preferred habitat is moist forests with plenty of shelter, such as rocks, logs, pieces of tree bark, and leaf litter. In Missouri, red-bellied snakes are commonly encountered on rocky, north-facing, wooded hillsides.

This species overwinters beneath large rocks, in ant mounds and mammal burrows, in rock crevices, and possibly in rotting logs.

Food

Food includes slugs, land snails, earthworms, and occasionally soft-bodied insects.

Biologists suspect that the blunt head and elongated teeth of this snake and the closely related Dekay's brownsnake helps them to grip and tug persistently on a snail's body until the snail fatigues and can be pulled out of its shell. An odd lip-flaring behavior in this species might be an adaptation for feeding on slippery, slimy slugs, snails, and worms.

Status

Harmless nonvenomous snake.

Because of its diet including slugs and snails, which are considered by many to be injurious to cultivated plants, this snake is generally considered beneficial to human interests.

Life Cycle

Courtship and mating take place in the spring, summer, or autumn. Females give birth to live young between late July and early September. A litter can contain 1–21 young. Individuals attain sexual maturity after about two years of life. Lifespan is at least 4 or 5 years.

Human Connections

This species is not known to bite and is docile and gentle when handled. Freshly captured, it will secrete a musky odor from glands at the base of the tail. Sometimes it plays dead.

People out enjoying Missouri's Katy Trail on warm, sunny October days often see red-bellied snakes crossing the gravel path as they migrate from the floodplains up to their overwintering habitat in the rocky, wooded hillsides.

Many snake species are burdened with unfair, undying myths that paint them to be much more dangerous and harmful than they are. But persecuting this small, harmless species is especially unjust, for it results from ignorance and fear.

Ecosystem Connections

As predators, these snakes control populations of the invertebrates they consume. But snakes are preyed upon themselves. Their defenseless newborns are gobbled by numerous animals. The adults, being small and defenseless except for playing dead or smearing stinky stuff on their captors, are eaten by many animals.

Many other animals feign death to escape predation, including opossums, hog-nosed snakes, wood ducks, mallards, several types of beetles and spiders, and more. In many cases, this behavior isn’t an “act” so much as it is a kind of unconsciousness caused by sheer fright. “Playing dead” may persuade the attacker to give up, or it may cause the attacker to hesitate long enough for the prey species to escape.