Pawpaw is a large shrub to small tree with a slender trunk and broad crown; grows in colonies.

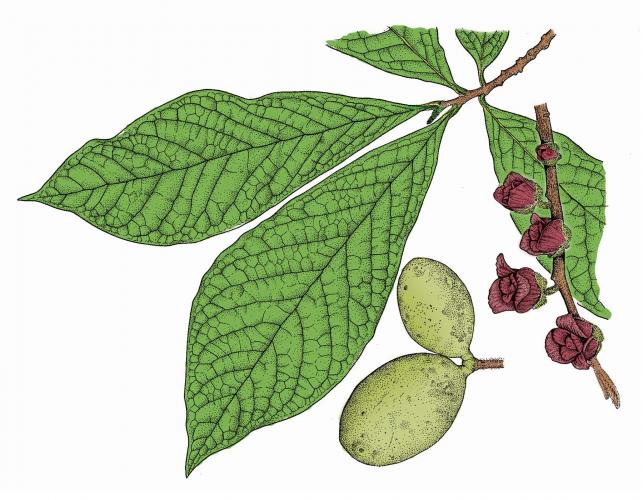

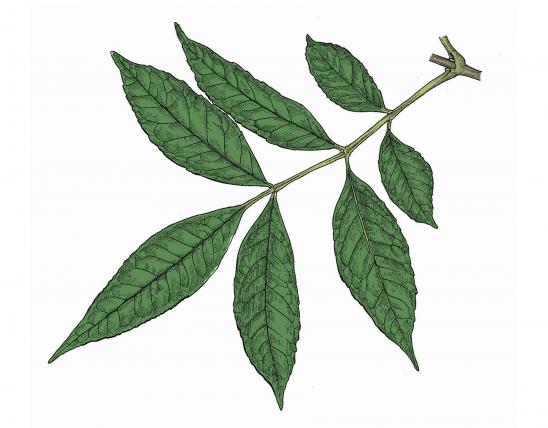

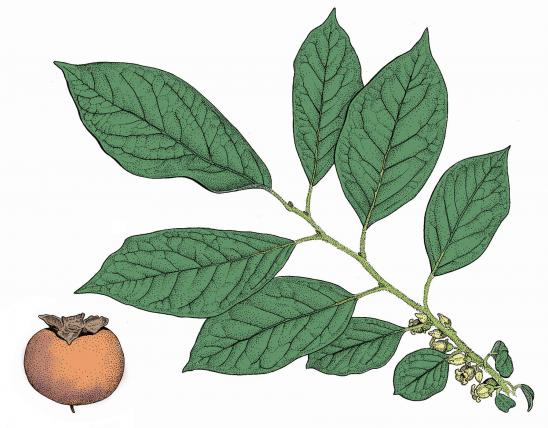

Leaves are alternate, simple, 6–12 inches long, 3–5 inches wide, broadest above the middle; margin lacking teeth; upper surface green; lower surface pale; emitting an odor when bruised.

Bark is light ash to dark brown, thin, smooth, later becoming warty with blotches.

Twigs are slender, olive-brown, often blotched, smooth, becoming rougher when older, often with a warty surface. Emits a disagreeable odor when crushed; terminal bud velvet brown, lacking scales; flower bud rounded, overwinters on previous year’s twig.

Flowers March–May; perfect (with male and female parts in same flower), dark reddish purple, solitary, drooping, about 1 inch across, appearing before the leaves and with an odor of fermenting purple grapes.

Fruits September–October. Banana-shaped, cylindrical, 3–5 inches long, green at first and yellow when ripe; pulp sweet, edible, with custardy texture.

Height: to 30 feet; grows in colonies.

Statewide, except for some of the far northern counties. May be cultivated statewide.

Habitat and Conservation

Grows in dense shade on moist lower slopes, ravines, valleys, along streams, and at the base of wooded bluffs. Produces suckers from the roots, forming groves or thickets. The leaves turn yellow in autumn and remain on the tree late into the season. Pawpaw is a member of a tropical family and has no close relatives in Missouri. In nature, it is associated with sweet gum, river birch, sycamore, and roughleaf dogwood.

Status

This species is becoming increasingly popular as a landscaping tree and fruit-bearing ornamental.

Human Connections

In 2019, after lobbying and testifying by a group of St. Louis students, the pawpaw was named Missouri's official state fruit tree.

“Way down yonder in the pawpaw patch” is an old song you might be familiar with — but today, surprisingly few Missourians know a pawpaw tree when they see one.

Pawpaw is increasingly popular as a native landscaping and fruit tree and has become one of the top choices as an edible native tree. New cultivated varieties are becoming available. If you want fruit, plant two unrelated trees so they can cross-pollinate.

The sweet fruit is eaten raw or baked. There are many recipes for it. It has even been used for flavoring beer! Some towns in the eastern United States have begun having annual pawpaw festivals.

The wood has no commercial use, but the inner bark was woven into a fiber cloth by Native Americans, and pioneers used it for stringing fish.

Pawpaw extract is being studied as a possible cancer-fighting drug. There are many historical medicinal uses.

There’s a Paw Paw village and a Paw Paw Creek in Sullivan County, in northern Missouri.

If you love tropical fruits, you might be familiar with some other species that are in the same family: the cherimoya, custard apple, sweetsop, and soursop (or guanábana). All have a sweet banana/pineapple flavor, a creamy texture, and the same basic green-skinned, multiseeded fruit structure. If you’re hankering for pawpaws and they’re out of season, try looking for their relatives in the produce sections of groceries, especially international groceries that sell Asian or Latin American fruits.

The name “pawpaw” apparently is derived from the Spanish word papaya, which is the name of an unrelated fruit that nevertheless also has big leaves and big, juicy, green-skinned fruits. Papayas were often called pawpaws by English speakers in the Caribbean in the 1500s and 1600s. When English speakers later encountered Asimina triloba, they applied the name to that species.

Pawpaws in Missouri history: In the middle of September 1806, the famous Lewis and Clark expedition up the Missouri River was nearly over. The men were in today’s state of Missouri, hurrying back downstream to St. Louis. The explorers ate their fill of juicy pawpaw fruits, which grow abundantly in river bottoms and are perfectly ripe that time of year. It sure beat dry, hardtack biscuits! But a number of the men soon complained of irritated, swollen eyes. There are several theories explaining their ailment. One possible explanation is that the men were suffering from an allergic reaction to pawpaw sap; perhaps they had rubbed their sensitive eyes after picking and handling the fruits. It all ended well, and the expedition arrived in St. Louis on September 23.

More pawpaws in history: There is so much to tell about this fascinating native fruit! The Native Americans whose homelands include the range of pawpaws have, of course, enjoyed them as far back as anyone can remember. They cultivated it, and they have names for it in their languages. The Kansa call it tózhaⁿ hu. The Choctaw call it umbi. The Pawnee call it riwahárikstikuc.

George Washington is said to have enjoyed chilled pawpaw as a dessert; some say it was his favorite.

Ecosystem Connections

The fruit is relished by numerous bird species and by squirrels, opossums, and raccoons. Often these creatures find the pawpaws before human pawpaw hunters do, which is one reason many people are planting their own pawpaw trees!

The lovely black-and-white striped zebra swallowtail butterfly requires pawpaw leaves as its larval food plant, so if you want to see zebra swallowtails, go where the pawpaw trees live. Zebra swallowtails cannot live on any other plant: pawpaw foliage is where they develop as caterpillars, and that's where the females must lay eggs. So planting pawpaw trees helps our native zebra swallowtails, too!

Pawpaws produce toxic chemicals called acetogenins in their sap, which function to prevent insects and other herbivores from chewing their leaves. The zebra swallowtail is immune, however. Similar to the way monarch caterpillars ingest and store toxins from milkweed plants and gain protection from predators, zebra swallowtails are also protected by the distasteful or sickening chemicals gleaned from their larval food plant.

The pawpaw sphinx moth (Dolba hyloeus) is another handsome insect whose caterpillars eat pawpaw leaves. Look for this moth in the bottomland forests where pawpaw grows.

Pawpaw’s unusual flowers, which are the color of drying blood and emit a faint odor of rotting meat or rotting, fermenting fruits, are pollinated by blow flies, carrion beetles, and other insects that scavenge from decomposing fruits or dead animals. Pawpaws are not alone in this strategy; several other plant groups also produce “carrion flowers” pollinated by similar insects, such as the unusual succulent houseplant Stapelia, whose flowers look like gigantic puncture wounds.

Native trees like pawpaw play an important and irreplaceable role in our Missouri ecosystems, feeding insects and larger animals that are adapted to eating them. When you plant native trees and other plants, you are strengthening the fabric of nature and helping to offset habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation.