Northern map turtles are medium-sized aquatic turtles that have a low ridge or dorsal keel along the center of the upper shell (carapace). The hind edge of the upper shell is strongly serrated (saw-toothed). The upper shell may be brown or olive brown with a netlike pattern of fine, squiggly, yellow lines that give the shell the appearance of a road map. The lower shell (plastron) is light yellow; the seams between the scutes (shell scales) are dark brown. The head, limbs, and tail are dark brown to nearly black, with many narrow, greenish-yellow lines. A distinct, small, yellow marking is located behind each eye that usually has a slight projection that is oriented toward the neck.

Northern map turtles are strong swimmers; their limbs are fully webbed. Basking northern map turtles are easily disturbed and will quickly scramble into the water.

Similar species: To identify our three map turtle species, look at the yellow markings near the eye. Ouachita map turtles have a large, wide yellow mark behind each eye that is widest just behind the eye and becomes narrow on top of the head. False map turtles have a thick yellow line behind each eye that extends upward, then backward, forming a backward L shape (these markings are variable, however).

Adult females are larger in size and have much larger heads than males. Adult upper shell length: 6¾ to 11½ inches (females); and 4 to 6½ inches (males).

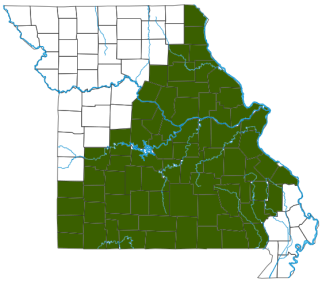

Statewide except for northwestern third and southeastern Missouri. Occurs principally in the Ozark Highlands, with the range extending northward through the eastern half of central Missouri to along the Mississippi River in northeastern Missouri.

Habitat and Conservation

Northern map turtles are active from late March to October. In Missouri, they occur primarily in small- to medium-sized rivers, reservoirs, sloughs, and oxbow lakes. They require many basking sites, a gravel or rocky bottom, and some aquatic plants.

They are often seen basking on logs and rocks sticking out of the water during the active season but will take advantage of unusually warm, sunny days in winter to bask. Hatchlings and young adult northern map turtles will often bask away from adults on floating algae mats, small logs, and rocks. Adults may bask up to eight hours per day and can be seen basking in a group of 10 or more on logs or large rocks. They will share prime basking sites with other turtle species.

In winter, northern map turtles generally stay on or near the bottom, in deep pools (10 to 20 feet). In a river in Virginia, they have been reported to congregate in groups of up to 100 individuals. They do not eat any prey during this time. The northern map turtle has been observed overwintering individually or in small groups (five or fewer) in rock crevices, between large rocks, inside large root wads, and under large, submerged logs along the bottom of several Ozark streams. Several authors have reported that this species remains active in winter and has been seen swimming under the ice, with males being more active than females.

Food

Foraging takes place in early morning and late evening. Males apparently utilize sections of rivers with more aquatic plants than do females. The diet of northern map turtles varies between the sexes; adult males eat snails, small mussels, and a variety of aquatic insects, especially caddisfly and mayfly larvae. The much larger adult females eat crayfish, snails, a variety of other freshwater mollusks, and some insect larvae. The females' larger head allows them to crush these prey, discard their exoskeletons or shells, and swallow the bodies.

A study of northern map turtles in the Niangua River in Missouri showed that small snails were the most common prey, followed by crayfish and then aquatic insects. A Pennsylvania population of this species living in Lake Erie was reported to feed heavily on zebra mussels, which are an aquatic invasive species in North America.

Status

This is the most widespread map turtle species in the United States, and it is the most common turtle species observed when floating or snorkeling on Ozark streams.

This species used to be called the “common map turtle,” but biologists are avoiding the word “common” in names, since it might mislead people into thinking these animals are abundant, when in fact they simply have a widespread geographical distribution. Broadly speaking, population numbers of amphibians and reptiles have been declining due to habitat destruction and degradation, indiscriminate use of pesticides, and pollution.

Life Cycle

Courtship and mating usually occur from late March through May, although in several other states this species has been observed breeding in autumn. From late May into early July, females travel on land to find a suitable nest site, along the edges of plowed fields, in patches of sand, or in clay banks. There may be 1–3 clutches of 6–15 eggs per season. These usually hatch from August through September. Eggs that were laid late in the season can overwinter in the nest, and the hatchlings emerge the following spring.

Males usually become sexually mature at around 4 years of age, and females at around age 10.

Human Connections

Basking northern map turtles are easily disturbed by a passing canoe or boat and will quickly scramble into the water. The availability of prime basking sites may be as important to the survival of map turtles as the availability of prey. The heavy use of many Ozark streams and rivers by canoes and inflated rubber tubes can negatively affect Missouri’s northern map turtle population. Simply put, this traffic prevents turtles from basking and may, in turn, reduce survivorship.

The netlike pattern of fine yellow lines on the carapace of map turtles can look a lot like a road map, hence their name. The species name, geographica, also refers to the maplike pattern. This species is declining in much of its range and is listed as endangered in Kansas, Kentucky, and Maryland.

In Europe, a nonnative population of northern map turtles occurs in the Czech Republic. These turtles became established when pet turtles were released or escaped from captivity. However, they and the native turtle species in that region are threatened by nonnative, invasive populations of red-eared sliders (also from North America).

Ecosystem Connections

Although mussels, snails, and crayfish have evolved shells to protect themselves from predation, the predatory female map turtle has evolved strong jaws to crack those shells. Northern map turtles may turn out to be a blessing in places where the invasive zebra mussel has been introduced. They are also reported to eat Asian clams, another invasive species.

Natural predators of northern map turtles include raccoons, striped skunks, and red foxes that dig up and eat freshly laid turtle eggs. Newly hatched turtles may be eaten by crows, otters, and coyotes.

Basking in the sun is common not only in map turtles but also in a wide variety of turtle species. Basking benefits turtles in a number of ways. It helps them to raise their core body temperature to optimum levels (thermoregulation). It also helps reduce the number of external parasites (such as leeches) and can reduce the amount of algae growing on their upper shells. In addition, warming in the sun increases their ability to digest and assimilate food, and direct sunlight allows their skin to produce vitamin D. Females will bask longer than males as this increases the speed of egg development.

The northern map turtle is a member of family Emydidae (the pond and box turtle family). This is one of the largest families of living turtles in the world. It comprises 12 genera, containing 52 species. In general, turtles in this family are small to medium sized and are adapted to a variety of habitats. This family includes several colorful species. Although the majority of species are aquatic (such as the eastern river cooter), several kinds are either semiaquatic or have taken to life on land (for example, the box turtles). In Missouri, this family is represented by 7 genera with a total of 11 species and 1 additional subspecies.