The adult central newt is a small, slender aquatic salamander without external gills or costal grooves (vertical grooves along the sides). The back is olive brown and the belly bright orange yellow. The dark color of the back and the yellow of the belly are distinctly separated along the sides of the body. Some very small red spots ringed with black may be along the back on both sides of the spine. Numerous small black spots usually cover the body; the black spots may be somewhat larger on the belly than on the back. A dark line runs from the nostril through the eye to the forelimbs. The eyes are often orange yellow.

For a couple of years in the middle (“eft”) stage of their life cycle, central newts live on land. Efts are dull brown to reddish brown or cream-colored, with a rounded tail and rough, almost bumpy skin. The youngest, larval individuals are aquatic and have gills. Upon hatching, they are about ¼ inch long.

Similar species: The central newt is Missouri's only newt. It is the only subspecies of eastern newt that occurs in Missouri, but elsewhere in the species' range, there are three other subspecies: the red-spotted newt (N. v. viridescens), broken-striped newt (N. v. dorsalis), and peninsula newt (N. v. piaropicola).

Adult length: 2¼–4¾ inches, occasionally to 5½ inches; efts 1½–3½ inches.

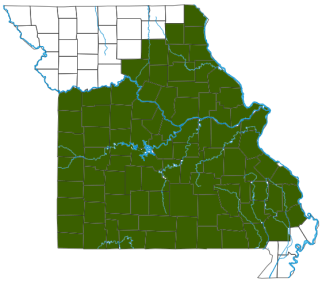

Throughout the southern two-thirds of the state, except for extreme southeastern Missouri; absent from the prairie regions of northwestern Missouri.

Habitat and Conservation

Adults live in woodland ponds, swamps, and occasionally water-filled ditches. They are seldom numerous in ponds that harbor fish or that lack aquatic plants. But a small, fishless, undisturbed pond may contain a surprisingly high number of adult newts.

Newts are active day or night and may be seen from shore as they swim near the surface, come up for air, or hover in midwater. Newts remain active throughout the year and have been seen in winter swimming under ice.

If their pond is drying and adult newts are forced to leave it, they probably travel to a deeper pond in the area or remain on land near their original pond, awaiting rainfall.

Newts are mainly found in forested regions, especially the Ozarks.

The efts take shelter under logs, rocks, or piles of dead leaves in wooded areas and may travel far from the ponds they hatched in.

Food

Adult newts eat mainly worms, small mollusks, crustaceans, insects, leeches, amphibian eggs, salamander larvae, and small tadpoles.

The terrestrial efts eat small insects and tiny snails they find under logs and rocks.

The aquatic larvae eat smaller aquatic invertebrates.

Life Cycle

Newts have a complex life cycle, generally having four stages: egg, aquatic larva, terrestrial juvenile (the land-dwelling eft), and aquatic adult. Breeding occurs in late March through early May. Fertilization is internal. Over a period of weeks in April through June, a female can lay 200–375 eggs, singly, on aquatic plants. These hatch after 3–5 weeks. The gilled larvae live in water until mid-July or early September, but some do not leave the pond until October. At this point, they transform into rough-skinned, land-dwelling efts without gills. As efts, they live 2–4 years on land, hiding in leaf litter, under logs and rocks, or in rotten stumps. Then, they return to a pond or swamp, change into aquatic adults, and spend the rest of their lives mostly in water.

Most adult newts are generally between 3 and 8 years of age, but some individuals may live as long as 13 years.

Human Connections

Humans can play a role in protecting our newt populations. The presence of fishless woodland ponds, swamps, and small sloughs is vital to the existence of this species. Efts require downed logs, brush piles, and other forest floor debris to survive their sojourn on land. If you own land, provide or protect these habitat elements.

Central newts in Missouri are often infected with amphibian chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd). This fungus infects the skin of salamanders and frogs, and it has caused massive die-offs of many amphibians around the world. The spread of the disease appears to have been accelerated by human activities, such as the pet trade and other movements of amphibians from one region to another. However, newt populations in Missouri appear stable despite carrying the fungus. Herpetologists must continue to monitor Missouri newt populations in Missouri for this fungus and other introduced pathogens.

Experienced crossword-puzzle solvers know the curious words eft and newt, and the corresponding clues such as "young newt" and "adult eft," because the words are frequently used as connectors, thanks to their commonly used letters.

William Shakespeare is the one who gave us the phrase "Eye of newt, and toe of frog." It's from act 4, scene 1, of his play Macbeth, where a trio of witches stir their boiling potion and recite their famous incantation, which continues with "Double, double toil and trouble / Fire burn, and cauldron bubble" and "something wicked this way comes." It's a horrifying scene, especially for people today who appreciate amphibians, their role in nature, and the fact that many species are declining or endangered. Some people have suggested that "eye of newt" might actually refer to mustard seeds, which are small, beady, and dark, and often used by herbalists. Three species of newts occur in the British Isles, and none of them occur in North America.

Ecosystem Connections

Adult newts and efts have few natural predators because they produce toxic skin secretions that make them taste bad. Interestingly, one study showed the skin of efts to be up to 10 times more toxic than that of the aquatic adults.

This species is the only representative of its family in Missouri. It is Missouri's only newt.

Scientists have suggested several explanations for the remarkable life cycle of newts. The terrestrial eft stage is apparently an adaptive boon when natal ponds are small, likely to dry up, crowded with newt larvae or other animals competing for food, and/or likely to hold predators, and when nearby terrestrial habitats offer plenty of food compared to the natal pond. Also, moving onto land encourages dispersal of individuals, which then can discover new ponds and unrelated newts to mate with.