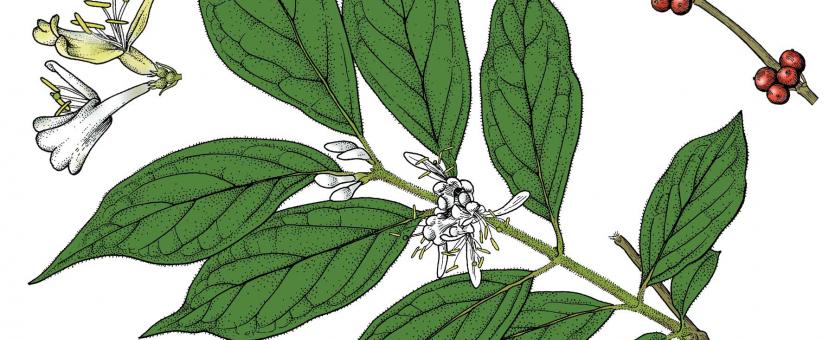

Bush honeysuckles are large, upright, spreading shrubs reaching up to 15–20 feet in height, with flowers that change from white to yellow; juicy red berries; and opposite, simple leaves that green up much earlier than surrounding native vegetation.

Leaves are deciduous, opposite, simple, 1–3 inches long, narrowly oval with a rounded or pointed tip, the margin entire (not toothed or lobed); upper surface green, lower surface pale green and slightly fuzzy. In late autumn, leaves typically remain green and attached well after the leaves of our native trees and shrubs have fallen.

Bark is grayish brown, tight, with broad ridges and grooves.

Twigs are grayish brown, thornless; the older branches are hollow.

Flowers May–June, fragrant, paired, growing from the leaf axils, tubular, 1 inch long, slender, distinctly 2-lipped, with upper lip having 4 narrow lobes, lower lip with 1 narrow lobe. Petals change from white or pink to yellowish as they age.

Fruits mature in September–October; typically red berries about ¼ inch across, 2–6 seeded, in pairs in the axils of the leaves.

To distinguish between the two invasive bush honeysuckles, note the following technical descriptions:

- Amur (L. maackii): leaf blades are tapered at the tip. The stalk below the paired flowers is 2–5 mm long (sometimes to 8 mm) (less than ¼ inch). The fruits appear sessile (stalkless). It is larger, to 20 feet tall, with leaves 2–3 inches long.

- Bella hybrids: leaf blades are rounded or broadly angled to a bluntly or sharply pointed tip, sometimes tapered abruptly to a minute, sharp point. The stalk below the paired flowers is 5–19 mm long (about ¼–¾ inch). The fruits appear noticeably stalked at maturity. These only reach 6–15 feet tall, with leaves 1–2½ inches long.

Similar species: Other native and nonnative honeysuckles that occur in Missouri are twining woody vines, not bushes.

Height: to 20 feet (Amur honeysuckle); 6–15 feet (bella honeysuckle).

Statewide. Infestations begin primarily near urban areas, where they escape from cultivation, but bush honeysuckles quickly spread to natural habitats and may be found nearly anywhere.

Habitat and Conservation

Understory shrubs in forests and woodlands; also in fencerows, thickets, roadsides, pastures, old fields, and unattended areas. Asian bush honeysuckles invade quickly and outcompete native plants.

In spring, because they leaf out so early, bush honeysuckles steal light from native plants, such as spring wildflowers and a variety of germinating seeds, which need a sunny forest floor in spring in order to flower, fruit, and gather energy for the next year. They also compete for soil moisture and nutrients. they may produce a chemical that inhibits the growth of native plants.

Then, in fall, bush honeysuckles remain green after other woody species have lost their leaves. This gives the bush honeysuckles extra strength and nutrition, which is another competitive advantage.

Birds and small animals eat the berries and deposit the seeds elsewhere, spreading these invasive weeds. When stems or branches are cut off, the plant resprouts with more branches, leaves, flowers, and fruits. Bush honeysuckles also spread from the roots, suckering to create new bushes nearby to further dominate an area.

Learn to identify these aggressive invaders, and then kill them before they spread more seeds elsewhere.

More information about the two types of bush honeysuckles in Missouri:

- The type called "bella" is an artificially derived hybrid between two Eurasian species, L. tatarica and L. morrowii, and represents a variable group of fertile hybrids. The various hybrids included within the "x bella" designation are difficult to distinguish from each other, requiring close examination of flower anatomy. Bella hybrids are more tolerant of moisture, so they may prefer habitats such as bogs, fens, lakeshores, and streamside areas.

- Amur honeysuckle (L. maackii) is a native of eastern Asia introduced widely for erosion control, as a hedge or screen, and for ornamental purposes through the mid-1980s, when its invasive potential was first realized. It had largely replaced other types of bush honeysuckles in the horticultural industry. Now it covers large areas in metropolitan areas, bottomlands, forests and woodlands, land along streams, in fencerows, gardens, railroads, roadsides, and shaded, disturbed areas. It is aggressively invasive in most midwestern states and has become the dominant species in the understory of many remnant wooded areas in and around cities. It has used rivers and highways as dispersal corridors to invade rural parts of the state.

Status

Invasive. Originally from Eurasia; introduced for landscaping, wildlife cover, and erosion control.

Bush honeysuckles are probably the most aggressive exotic plants that have escaped and naturalized in urban areas, where the woodland understory is often a solid layer of green from these shrubs.

Bush honeysuckles tolerate many habitats and can become established nearly anywhere that birds can go.

Prescribed burning, hand pulling of seedlings, cutting and applying herbicide to the stumps, and other herbicide treatments are all employed to try to control this tough, weedy plant. See the link to "Control" below.

Control

Human Connections

Don’t think of planting this species in your yard — instead, use a native alternative such as American beautyberry, American hazelnut, buttonbush, Carolina buckthorn, elderberry, or deciduous holly. Crabapples, plums, and shrub dogwoods are also excellent choices.

The berries of bush honeysuckles are mildly toxic to humans but are strongly bad-tasting.

Learn to identify bush honeysuckles and help in the fight to control their expanding numbers. There are several methods for controlling them.

Ecosystem Connections

Bush honeysuckles shade out native wildflowers and young native trees on the forest floor. They compete with native plants for soil moisture and nutrients.

They compete with native plants for pollinators, resulting in fewer seeds set on native species.

They may also secrete a chemical into the soil that hinders native trees.

By dominating the understory of a woodland, they change the very structure of the natural community.

Birds tempted to nest in the sturdy lower branches of bush honeysuckles suffer higher nest predation, being closer to the ground.

The berries of bush honeysuckles, though abundant, are carbohydrate-rich and do not provide the high fat content required for the long flights of migrating birds.