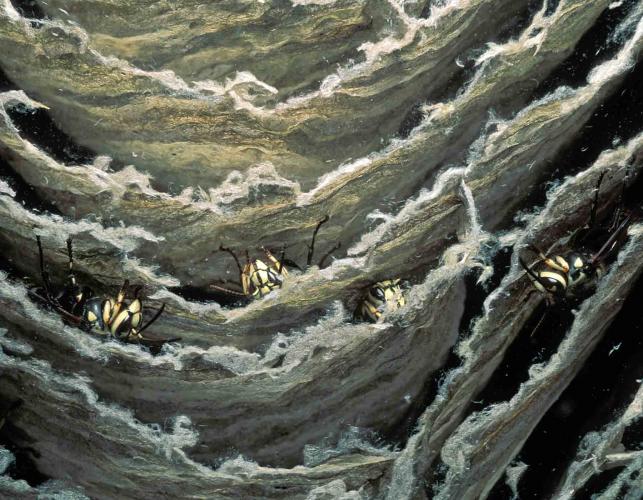

The bald-faced hornet is a fairly large wasp that is mostly black, with white or ivory markings on the face, thorax, and toward the tip of the abdomen. The wings are translucent dark brown.

In winter after leaf-fall, look up into trees for old nests, which are large, rounded, papery, and gray. You have probably seen one of these nests in a natural history display. Unlike the wasps we usually call yellowjackets, this species is not yellow. Its larger size and black and ivory coloration make it easy to distinguish as a distinct type of social wasp.

Length (excluding appendages): ½ to ¾ inch (workers); ¾ inch (queen)

Statewide.

Habitat and Conservation

Bald-faced hornets build their nests in trees and shrubs and construct them out of wood pulp (literally paper). These wasps chew wood, mixing it with starches in their saliva, and use this substance to make the nest. Nests eventually have several layers of horizontal comb enclosed by an outer envelope, just as yellowjacket nests do. Each nest is begun in spring by a single overwintered queen. Late-summer nests may contain several hundred workers, as well as males and new queens. Bald-faced hornet nests are often so high off the ground they pose little problem for people.

Food

Adults generally eat nectar from flowers, but they collect insects and other arthropods to chew up and feed to their growing larvae.

Status

Unlike solitary wasps, social wasps are likely to sting intruders to defend their nest, if they sense that their nest is endangered. For this reason, when they build nests near people, they may become a nuisance. Certain persons may be allergic to wasp stings, and their health may be endangered if stung. If you wish to remove a wasp colony, consult licensed professionals and follow pesticide instructions carefully. When the nests of these wasps are away from buildings and sidewalks, however, these insects present little danger to people and should be tolerated and appreciated for their role in nature.

Life Cycle

In spring the overwintering queen starts building the nest and lays her first eggs. She feeds these larvae, which become infertile female workers. Workers are the most commonly encountered by people, as they do most of the work outside the nest, while the queen specializes in egg-laying and stays at the nest. As winter begins, the queen lays eggs that become new queens and male drones. Once these mature and mate, and temperatures drop, all die except the fertilized young queens.

These and other “eusocial” (highly social) wasps represent a peak of insect social development. Each colony is a family, all descended from a single queen. The queen hibernates over winter in a protected place, emerges in spring, and lays the eggs for the whole colony. Scientists call the colonies of eusocial insects “superorganisms” because the division of labor is greatly specialized, individuals cannot survive on their own, and it takes the efforts of the entire colony in order to reproduce itself.

Human Connections

Aggressive nest defense makes these wasps a stinging threat, but their foragers do not collect sweets or food scraps and are not aggressive away from the nest. Like all wasps, bald-faced hornets do much that benefits human interests and should not be destroyed indiscriminately.

Ozark folklorist Vance Randoph, writing in the 1940s, reported that "nearly every old-time mountain cabin" had an empty hornets' nest hung up in the loft, and that people even tied them up in newly built homes that were not yet occupied. The nest was supposed to bring good luck to everyone in the household, especially regarding childbirth and other reproductive matters.

Ecosystem Connections

As predators, these wasps spend their days hunting many types of insects and spiders. As nectar eaters, they play a role in pollinating plants. And despite their formidable defensive capabilities, these wasps certainly can become food for numerous larger predators.