Winter is tough for wild critters. Keeping warm in freezing weather uses lots of energy. And food gets hard to find when snow starts to blow. So how do animals survive these cold, dark months?

Some say, “See ya!” and skedaddle south where it’s warmer. Others tough it out and prowl the frozen countryside looking for meals. And some critters — the ones this story is about — simply use less energy.

Super Snoozers

Eastern Chipmunk

In the fall, an eastern chipmunk has just one thought in its furry little head: storing enough food for winter. It gathers nuts and acorns and stuffs them in its cheeks like you might fill a supermarket sack. Then it scurries to its underground den to unpack its “groceries.”

A single chipmunk can pack its underground pantry with enough seeds to fill nine 2-liter soda bottles.

When winter arrives, the sleepy squirrel builds a bed atop the pile of food and dozes on and off until spring.

At first, its bed is near the roof of its den.

But as time goes on, the hungry ’munk eats more and more of its seed stash, and its bed sinks to the floor.

American Black Bear

To pack on a thick layer of fat for winter, bears gobble acorns, insects, and other food. At the peak of their feast-fest, they can gain 40 pounds a week!

In November or early December, they search for cozy spots to take a looong winter nap. Some rake leaves into a cave or crevice. Others take shelter in a hollow tree or under a fallen log. While they’re snoozing, they don’t eat or drink. Instead, they rely on their fat for energy.

In January, mama bears give birth to two or three itty-bitty cubs. While mom continues to snooze, the cubs drink her milk to grow bigger and snuggle against her to keep cozy.

During winter, black bears go nearly 100 days without peeing or pooping.

Western Painted Turtle

Western painted turtles spend winter underwater. When temperatures drop, their body functions slow down. They need only a tiny bit of oxygen to stay alive, and they get it by moving water over a part of their bodies that biologists call the cloaca (cloe-ay-kuh). Most people call it something else: rear end.

Surviving with little oxygen for dozens of days has a downside: Turtles wake up with terrible muscle cramps! To get rid of them, they find a warm spot where they can soak up some sun. This helps them produce vitamin D, which combats the cramps.

Going without oxygen causes acid to build up in a turtle’s muscles. To neutralize the acid, turtles steal calcium from their shells.

Snakes

Before the weather turns shivery, snakes get slithery. They wriggle into abandoned woodchuck burrows, caves, and cliff crevices — any place the temperature stays above freezing.

As they slither, they leave a trail of scent that other snakes can follow. That’s how dozens — sometimes hundreds — of snakes end up tangled together in winter dens.

During summer, a kingsnake would happily gobble a gartersnake. But during winter, snakes lose the desire to eat.

Every winter, a cave in Canada that’s no bigger than your living room becomes home to tens of thousands of eastern gartersnakes.

Hardcore Hibernators

Woodchuck

Every October, in fields and forests across Missouri, woodchucks waddle into their burrows, curl up in leaf-lined beds, and switch their bodies to “standby.”

Their lungs and hearts grind nearly to a halt. Blood that once gushed in their veins creeps to a trickle. Electricity zipping around their brains fizzles out. And their body temperatures plummet to a few degrees above freezing.

This slowed-down state is called hibernation (high-bur-nay-shun). It helps animals conserve energy during hard times so they don’t need to eat or drink.

If you dug up a woodchuck in winter — we don’t advise it! — you could toss it around like a furry football for hours before it would “wake up.”

13-Lined Ground Squirrel

Woodchucks hibernate for about three months, but that’s merely a nap compared to the super-sized siestas taken by its striped cousins.

Thirteen-lined ground squirrels plow through prairies in northern and western Missouri. As their name suggests, they live underground.

When they aren’t digging tunnels, they spend time stuffing their pie-holes with anything they can get their furry paws on. Seeds, fruits, grass, insects, worms, eggs, lizards, mice — they all go gulp. In no time, the once-skinny squirrels have nearly doubled their weight.

At the end of summer, ground squirrels crawl into their burrows, drift deeply into hibernation, and don’t wake up until … yawn … seven months later!

During hibernation, a ground squirrel’s heart rate drops from 250 beats a minute to five, and it goes from taking 50 breaths a minute to four.

Indiana Bat

Indiana bats are picky about where they hibernate. The furry flyers need just the right mix of temperature and humidity to survive, and only a few caves meet those conditions.

Luckily, several spots in Missouri fit the bill, and over a third of the world’s Indiana bats spend winter beneath the Show-Me State. They hang upside-down from the damp walls, crowded together in clusters of hundreds or thousands of bats. Sometimes close cousins, like gray bats and little brown bats, join the sleepover.

You can pack a boatload of bats in a small space. A single square foot of cave wall can contain up to 500 hibernating bug-munchers.

Meadow Jumping Mouse

Meadow jumping mice fall asleep in the fall not knowing if they will wake up in the spring.

In September, this bouncy mouse tunnels into a grassy slope and builds a nest. When its bed is ready, the mouse tucks its head between its hind legs and wraps its tail around its body.

Curled up in a golf-ball-sized lump, the little mouse hibernates for up to seven months. Unfortunately, nearly two-thirds of all jumping mice don’t wake up from their dirt naps.

Sproing! When frightened, a meadow jumping mouse can leap up to 12 feet in a single bound.

Frozen Alive

Boreal Chorus Frog

A boreal chorus frog spends winter chilling out — literally. When icy weather hits, the thumb-sized frog quits breathing, its heart stops, and its body freezes nearly solid.

There’s only one problem. When water freezes, it expands. If water in the frog’s cells expanded, the cells would burst like overfilled balloons, and the little frog would … well … croak. But chemicals in the frog’s body cause ice to form around the cells, not inside them. And chemicals inside the cells keep them from freezing.

Male chorus frogs sing in the spring. Their calls are a raspy preeeep that sounds similar to running your fingernail over a comb.

Mourning Cloak Butterfly

Mourning cloak butterflies spend winter huddled in tree cavities or under loose bark. Though the upper sides of their wings are brightly colored, the undersides are well-camouflaged. To hide from hungry birds and other insect-eaters, a mourning cloak simply folds its wings and disappears.

Antifreeze inside the butterfly’s body stops its cells from freezing. And extra fuzz on the outside of its body helps it trap heat.

On warm winter days — even when there’s still snow on the ground — keep an eye out for hungry mourning cloaks seeking tree sap to slurp. Their fluttery flight is a sign spring will soon be here.

To warm up its wing muscles for flight, a mourning cloak shivers. This raises its temperature 5 degrees or more.

In winter, some animals power down to stay around.

Also In This Issue

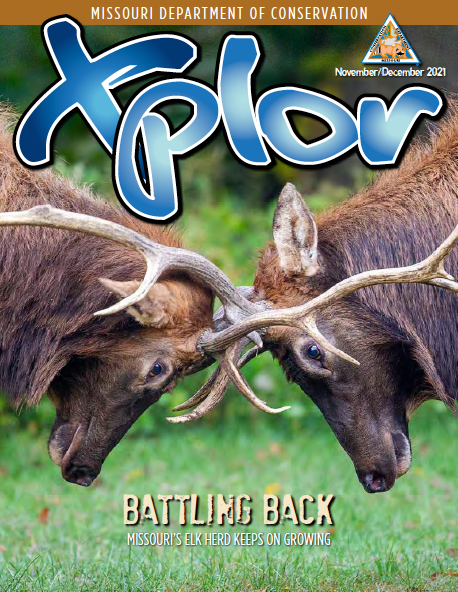

Missouri’s mightiest mammal makes a comeback

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Alexis (AJ) Joyce

Angie Daly Morfeld

Noppadol Paothong

Marci Porter

Laura Scheuler

Matt Seek

David Stonner

Stephanie Thurber

Cliff White