Enterprising investigators launched their voyage of snake exploration with a copperhead named Captain Kirk. Now they’re searching for mysterious reptilian life forms on the grounds of MDC’s Powder Valley Conservation Nature Center (CNC).

Ben Jellen holds an unusual, spindly metal apparatus in the air, then parallel to the ground, then dipping downward. An electronic device at his side spits radio static from electronic blips that grow louder or softer as he slowly moves about. When the blips reach their highest volume, Jellen stops and scrutinizes the ground carefully, using his hand-held antenna as a divining rod.

This scientist is not divining for water — he’s seeking out snakes. The radio tracking device tells him that his quarry is right there, but his eyes can’t see it. The snake has retreated underground, choosing to avoid confrontation and seek safety in the subterranean world.

Voyage of the Copperhead Scientists

Jellen is on a multi-year mission to seek out new information about the life of the eastern copperhead. His objective is to study Agkistrodon contortrix, one of Missouri’s five venomous snakes — and the state’s most commonly encountered venomous snake species.

The purpose of the journey is to gain insight into how these snakes live near a heavily populated and urbanized area like the one that surrounds Powder Valley CNC. The nature center’s 112-acre oak-hickory forest straddles the St. Louis suburban communities of Kirkwood and Sunset Hills and is bracketed by the intersection of I-270 and I-44. Powder Valley CNC offers a small world of natural habitat in a galaxy of residential and commercial development.

An associate professor of biology at the University of Health Sciences & Pharmacy in St. Louis, Jellen completed his master’s degree in natural resources and environmental sciences. As a passionate reptile and amphibian researcher, he’s been tracking snakes for over 20 years. In 2018, he was approached by MDC State Herpetologist Jeff Briggler to undertake the study.

Jellen’s second in command on this enterprise is Brittany Neier, an educator with the Saint Louis Zoo and recent graduate of Miami University’s Project Dragonfly program. Neier is making a point of studying the connections between copperheads and people.

The main questions posed by the project: Why, where, and how much do copperheads move? What do they eat and how long do they survive? What habitat do they use, and does it shift throughout the year? Where do they overwinter? And what do both people and snakes think when they encounter one another?

“Powder Valley is an ideal place to try to learn more about copperheads. This study can help with planning where trails should be in the future, to benefit both people and snakes,” said Briggler.

Detecting Alien Life Forms

Copperheads are secretive by nature. Evolution has gifted them with special coloring and scale patterns, a natural “cloaking device,” that allows them to blend in discretely with their surroundings. Just finding the snakes is a considerable challenge.

“It’s really about impossible to do without a little bit of help,” Jellen said. “That help comes in the form of technology, and the technology is radio transmitters.”

Jellen stressed that to obtain meaningful data about the creatures, scientists must find a snake, be able to follow its movements, and find it again consistently. Radio signals provide a beacon to help zero in on what would otherwise be an almost invisible snake. Since copperheads don’t readily transmit radio signals on their own, all the snakes that Jellen has “on the air” have been fitted with miniature radio transmitters. MDC purchased the initial transmitters and the Saint Louis Zoo performed the surgical transmitter implantations.

“The Saint Louis Zoo has been an amazing partner,” Jellen said, acknowledging it has provided all surgical implantation to support the study.

The delicate procedure involves anesthetizing the snakes, then making an incision two thirds down the length of the body on the lateral side. The veterinarian inserts the transmitter into the abdominal/pelvic cavity, running the antenna wire up just beneath the skin, then carefully stitches up the animal. After a 24-to-48-hour recuperation period, Jellen releases the snakes back to the exact location of their capture. No snakes are ever moved from one location to another in this study.

Transmissions From Captain Kirk

The key to the whole process was finding that first snake to get the study rolling. That’s when Captain Kirk came to the rescue.

The first snake in the study was a male copperhead encountered by World Bird Sanctuary staff while giving a demonstration at Powder Valley CNC. Once “on the air,” he proved especially adventurous. Jellen and Neier named this first copperhead Captain Kirk, both as a nod to the Kirkwood area and to the iconic character of the Star Trek TV show and movies. After all, the space-traveling Captain Kirk was known as a brave adventurer with an eye for the ladies.

“Getting a male is what you want because they’ll look for females. The males are the roamers, they’re the travelers,” said Briggler.

And roam he did. Captain Kirk boldly went, exploring the strange new worlds of Powder Valley CNC’s oak-hickory universe. His travels propelled him, at what must have been warp speed by snake standards, throughout most of the 112-acre property and beyond, leading the research team to three additional copperheads. Following Captain Kirk’s radio trail gave the study a jumpstart, and enabled the researchers to capture, implant, and track those snakes, too. Through a similar process, Jellen and Neier have succeeded in fitting 15 other copperheads with transmitters in the last three years.

Alternating tracking duties, Jellen and Neier have been following the copperheads each day from March to November since August 2018. Jellen has even gotten assistance from his 8-year-old daughter, Eve, who has accompanied him on his tracking runs. The research team has gathered about 1,400 radio locations since starting the study.

Where No Research Has Gone Before

One of the snakes captured in 2020 was a gravid female, which meant that the team had the chance to tag and track six newborn copperheads. Jellen estimates that fewer than 20 studies have been done on neonate snakes worldwide. This project is the first in history to specifically study copperhead newborns, placing it on the frontier of such research.

“This is definitely a rare opportunity,” said Briggler.

Female copperheads bear live young in the fall, and the neonates in this study were released in late September, complete with tiny transmitters attached to their bodies. Since they are the size of a pencil, newborn copperheads do not have room inside their bodies for implanting the devices.

A copperhead mother is not the doting type — she simply drops her babies and goes off to replenish her own depleted resources. The newborns receive absolutely no parental care. They must survive by instinct alone.

“So, here’s this little thing that’s just been born, and it’s just there. It has no instructions on how to live, no instructions on anything,” said Jellen. “And of course, the most important things for it are finding food and finding shelter. Nobody really knows how they do either.”

Jellen’s preliminary observations show that young copperheads are not at all bound to their mothers. The neonates in the study were content to go their independent ways.

“Not a single one of them wound up in the same place as their mom or followed her scent trail,” he observed. “The mom moved the least of all, only about 1.5 meters (4 to 5 feet) from where she gave birth to where she overwintered. Some of the babies moved as far as 150 meters (about 500 feet) total from their birth spot.”

In a 24-hour period, one infant travelled 106.5 meters (almost 350 feet) seeking an overwintering spot.

“For something that small to move that far, I was really struck by their mobility,” Jellen said.

The researchers consider it too early to draw definitive conclusions due to the small sample size, yet the neonate behavior is consistent with what we understand about the species in general.

“Copperheads are known to be more solitary, so they do spread out more. Their nature is not to cluster in large groups,” Briggler pointed out.

Since copperheads occur in a wider variety of habitats than other venomous snakes in Missouri, Briggler speculated that characteristic might explain their innate drive to explore, move, and disperse.

Mission Analysis

The project is still a work in progress, however, Jellen has observed some interesting trends from the data gathered so far.

For one thing, being a copperhead is dangerous business — for the snake that is. Jellen has been surprised by the high mortality rate for the snakes they’ve been tracking, which has been about 50 percent.

“On no study I’ve done have I had nearly as high a mortality rate. I’ve maybe lost one or two snakes to predation after three years in other studies. And right now, in the same three years, I’ve lost 10,” Jellen said.

Three snakes were struck by cars, one was swept away and drowned in a creek during a heavy rain event, and another asphyxiated from being trapped in a burrow. The most common death however, has been predation from birds of prey like owls and hawks. Mammals such as foxes, raccoons, coyotes, or skunks also take a toll. The average life span of a snake in the study? About one year.

“You’ve got heavily fragmented habitat, and a high level of traffic on multiple sides. I would probably expect a higher mortality rate because your predators are going to learn this is a better place to find prey,” suggested Briggler.

In such a setting, predators learn to focus in on the nature center’s area of good natural habitat amid the surrounding urban sprawl.

Jellen has seen some interesting trends regarding overwintering, too.

“Snakes use Powder Valley like people do. They come there when the weather is nice and then go back to their ‘homes’ to overwinter,” he pointed out.

Half the snakes in the study overwintered off the nature center property. Three chose to spend winter under nearby Cragwold Road, and another under the rocks building up the shoulder of I-270.

Briggler is not surprised, noting that finding a site with the right sun exposure is critical for surviving the cold months. This behavior is similar to snakes in the wild seeking open, rocky areas.

“The road cuts where rock has been disturbed, especially south facing ones, could provide the right sun angles and provide more warmth in winter,” he deduced.

How cold do the snakes get? The transmitters allow the research team to determine the snakes’ temperatures when they’re overwintering.

“They stay just above freezing” Jellen said. “The lowest temperature is about at 4 degrees Celsius, or about 40 degrees Fahrenheit.”

Finally, Jellen’s data indicated that the copperheads seem to make good use of Powder Valley CNC’s native grass plantings, like big bluestem, compass plant, and other perennial prairie plants. Briggler said this rang true with research he’s done, too. Rodents are more abundant on forest edges and big grassy fields, which draws the snakes.

“I think these grassy strips are really important for the snakes,” Jellen said, adding that it’s one aspect he’d like to explore further, and he’s begun a small mammal trapping study.

Close Encounters

In addition to tracking copperheads, Neier is also hoping to learn more about how people interface with snakes as part of her graduate work. With nearly 100,000 visitors annually, Powder Valley CNC is fertile grounds for exploring the relationship between snakes and humans, she said.

A lot of people are uncomfortable around snakes, and Neier has encountered a wide range of reactions from the public while out doing her copperhead research; everything from, “Why the heck are you doing that?” to “That’s awesome!”

“No matter where they landed on the spectrum, they all just wanted to know more, and as an educator, I found that to be an area to focus on,” said Neier.

She appreciates the curiosity from visitors, and always takes extra time to explain what she’s doing and what the study is all about.

As part of her exploration, Neier conducted a public outreach program in cooperation with the nature center staff that included displaying a live snake.

“There was a family with a mom who didn’t really like snakes, but she could see her kids were really interested,” she recalled.

Neier was impressed that the mother was willing to put her own discomfort aside to encourage her kids to see and learn about the snake. She hopes that education and understanding can minimize potential snake-human conflicts. She encourages visitors to ask questions of her and Jellen when they notice them at work.

“It’s such a great opportunity to see science in action,” she said.

Kirk Out

The starship Captain Kirk faced down a battalion of Klingons, a solar system-eating amoeba, and a man-sized lizard. The copperhead Kirk, however, became another one of the casualties; he was eaten by a hawk. Copperhead Captain Kirk beat the odds by surviving three years, an incredible accomplishment considering the hostile universe snakes face in the wild. And Jellen is confident he didn’t go without a fight.

While he lived, the intrepid copperhead kickstarted a pioneering research project. Captain Kirk performed above and beyond the call of duty and represented his species with distinction.

“Snakes are highly persecuted, and venomous snakes even more,” Jellen said. “To give them a voice is important.”

“People might be less scared of them if they know more,” added his daughter, Eve.

And the mission carries on. Thanks to a trailblazing copperhead named Captain Kirk and a “crew” of radio-tagged snakes, these enterprising researchers will continue to go where no scientists have gone before.

The Prime Directive: Non-Interference

One thing the copperhead study at Powder Valley CNC has revealed is that these snakes do cross the trails. They can often hang out unseen mere feet from the footpaths. But copperheads are highly reclusive and non-aggressive creatures that want little to do with humans. MDC State Herpetologist Jeff Briggler says he rarely gets a venomous snake report from the public on MDC areas.

“They prefer to get away from you and that’s why we have so few encounters. They really want to be left alone,” he said.

If you do see a copperhead on a trail, the logical course of action is to follow the prime directive: non-interference. Leave them alone, and they’ll likely return the favor. Don’t attempt to pick up the snake or harass it in any way. Most snake bites occur on the hands and arms from people trying to pick them up. Walk around the snake carefully, preferably from behind it, leaving plenty of space and giving it an escape route. Avoid making the snake feel cornered. And appreciate the fact that it might eat something you like even less.

To learn more about copperheads and other snakes in the Show-Me State, consult A Guide to Missouri’s Snakes, available online at short.mdc.mo.gov/ZhD.

There’s a place for all life forms, people and snakes included.

Join host Jill Pritchard as she talks with Ben Jellen and Brittany Neier about their copperhead research and goes with them on a snake tracking run in the latest episode of MDC’s Nature Boost podcast. You can find it at mdc.mo.gov/natureboost.

Also In This Issue

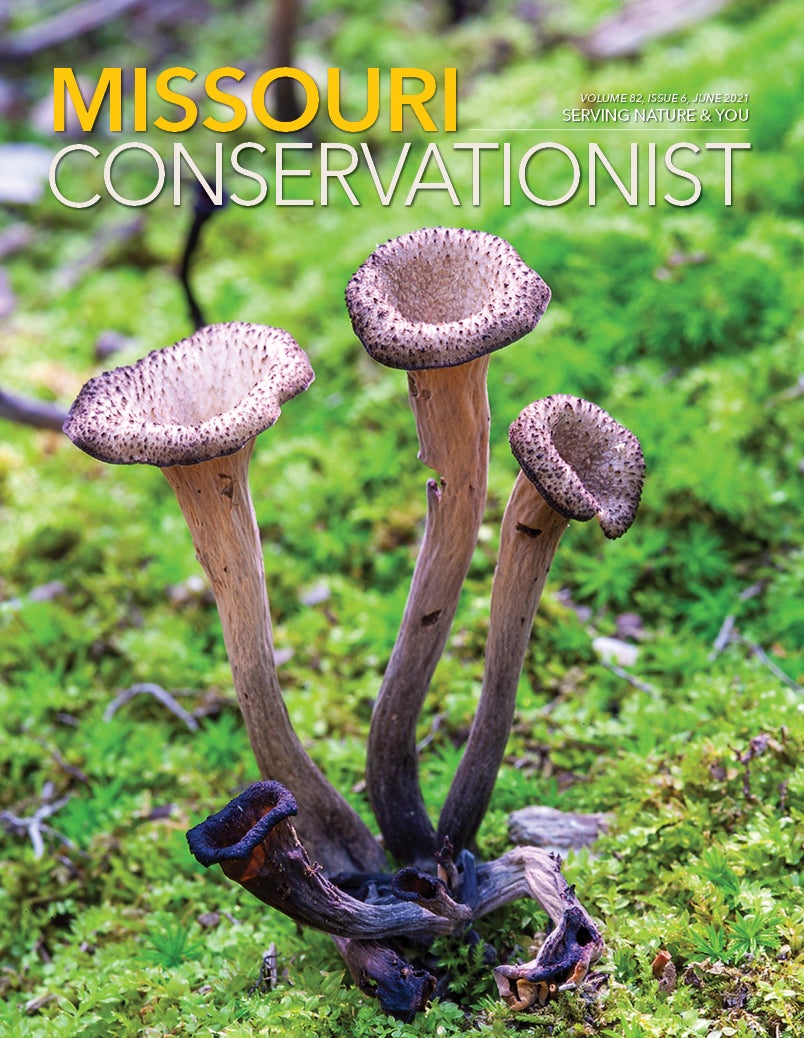

A buffet beyond morels.

Hard-fighting common carp make for challenging fishing, tasty fare

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Editor - Angie Daly Morfeld

Associate Editor - Larry Archer

Photography Editor - Cliff White

Staff Writer - Bonnie Chasteen

Staff Writer - Kristie Hilgedick

Staff Writer - Joe Jerek

Designer - Shawn Carey

Designer - Marci Porter

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Circulation - Laura Scheuler