If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.

That admonition encouraging healthy skepticism churned in the back of Mike Buschjost’s mind. The woman who had just called to congratulate him on winning the lottery seemed authentic. She spoke with the authority and knowledge one would expect of a woman in her position, but still, with all the details swirling around in his head, how could he be certain.

She gave me the information and it wasn’t 45 minutes later that I had to call her back just to double check to make sure I heard her right,” said Buschjost, a 40-year-old construction manager from St. Thomas. “I didn’t have anything in writing, so I thought, ‘Shoot, I need to call her back before I spread the word and get too excited.’”

Further in the back of Mike’s mind were those guys, the guys on Mike’s crew, who would like nothing more than to pull a fast one on the boss.

“We do play a lot of jokes back and forth,” he said. “We’ve got a lot of things going on in construction work, so that’s why I made sure to call her. I was like, I want to make sure no one was jacking with me. We’ve got a long line of practical jokers here on the construction job site.”

So, he called, and once again, he was speaking with MDC Director Sara Parker Pauley, who — once again — confirmed that his name was one of four drawn from more than 19,000 applicants seeking a general public permit to participate in Missouri’s inaugural elk hunt in October and December.

The Perfect Scenario

Pauley’s call to Buschjost in early June came nine years and a month from the date the first elk — six bulls and 28 cows and calves — were reintroduced to Missouri on May 5, 2011, after having been absent from the landscape due to unregulated hunting and habitat loss since 1865. Missouri Conservation Commission Chairman Don Bedell and former Commissioner Chip McGeehan, both of whom had voted in favor of elk reintroduction at a meeting in Kirksville seven months earlier, were among those assisting in the release at Peck Ranch Conservation Area (CA) in Carter County.

“It was one of the thrills of my life to be able to pull that gate open and see these elk,” said Bedell, who’s office lobby is adorned with a large photo of three collared bull elk.

The 23,762-acre Peck Ranch CA is at the core of a 346-square-mile elk restoration zone that includes parts of Shannon, Carter, and Reynolds counties.

The commission’s vote was unanimous, but not without controversy. Opponents to reintroduction — who had successfully blocked a similar attempt a decade earlier — continued to voice concerns about conflicts with agriculture, and the potential for motor vehicle accidents involving elk.

By quarantining the elk before release and establishing the elk restoration zone in an area with little agriculture or major transportation routes, MDC addressed the concerns to the commission’s satisfaction, McGeehan said.

“It was a legitimate concern, but we set up 350,000-plus acres,” he said. “It wasn’t the perfect habitat, but it was the perfect scenario for what we had.”

Since the reintroduction of the first elk, much of the skepticism has turned to enthusiasm, McGeehan said.

“Now we have cities fighting over who is the elk capital of Missouri,” he said.

With the addition of more elk in 2012 and 2013, MDC relocated a total of 108 elk from Kentucky to Peck Ranch CA. In the intervening years, the herd has more than doubled and has become a draw for nature watchers who want to catch a glimpse of the massive cervids and hear the bulls’ distinctive fall mating bugle. This draw has been a boon to the local economy, with a 2017 study estimating a $1.3 million boost to the area economy from visitors taking the elk viewing tours at Peck Ranch and Current River conservation areas in 2016.

“It’s going to have a big economic impact in one of the most depressed economic areas of our state in the rural part of the Ozarks,” Bedell said.

And the addition of an elk hunting season — albeit limited to begin — will increase those economic benefits, especially when it results in keeping Missouri elk hunters, who spend large sums to hunt elk in other states, in Missouri, he said.

“We’re keeping the money at home,” he said. “We’re supporting our local economy, we’re supporting our local Conservation Department, and enabling our department to do things they couldn’t do otherwise.”

Missouri Elk; Missouri Hunters

In addition to the general permits issued to Buschjost and three other Missouri residents, one additional permit was issued to a qualifying landowner with at least 20 acres within the “Landowner Elk Hunting Zone” in a portion of Carter, Reynolds, and Shannon counties. Thirty-three applications were submitted for the landowner permit, which allows the landowner to hunt only on his or her property within the landowner elk hunting zone.

The additional landowner permit was created to acknowledge the 20 percent of the elk restoration zone that is private property and the habitat work many of those landowners have done to make the area more elk friendly, said MDC Elk and Deer Biologist Aaron Hildreth.

“We have probably 85 or so private landowners in that area that are very active in habitat management, in the name of all wildlife, but many of them are certainly happy to see elk,” Hildreth said.

The inaugural elk season will take place in two parts that bookend the majority of the firearms deer hunting season. The first is a nine-day archery portion running Oct. 17–25, followed by a nine-day firearms portion running Dec. 12–20. The five permits will be for bull elk only and will be valid for both portions.

The permit drawings were limited to one application per-person, per-year with a 10-year “sit-out” period for those drawn for a general permit before they may apply again.

A Growing Herd

Before approving an elk season, the commission set three goals for herd health and sustainability: a minimum of 200 head, an annual growth rate of at least 10 percent, and a herd ratio of at least one bull per four cows. As of June 1, which MDC biologists consider the beginning of the elk biological year, the herd was estimated at 207 head, with a three-year average growth rate of 16 percent. Researchers and wildlife managers use radio collars, calf-cow counts, and aerial surveys to track the herd’s size and movement. Although the minimum herd size to sustain the population with a limited harvest was 200, the goal remains for the herd to grow to twice that size, Hildreth said.

“Right now, we have a population goal of around 500 elk,” he said. “Conceivably if everything holds true and the population continues to improve as the model predicts, we’ll be in excess of 400 individuals by 2025.”

As the herd grows, so is the likelihood that the annual harvest will grow as well, Hildreth said.

“Right now, we’re only hunting antlered elk so we’re having minimal impact on the reproductive side of the population,” he said. “But as we approach our population goal we’re going to survey the public to get a more current idea of acceptance trends — how well they like them, where they like them, all that good stuff — but we’re going to move from purely recreational hunting to population management, and a big part of that will be antlerless or cow hunting opportunities.”

A One-on-One Deal

Now that the reality — and the authenticity — of his historic call with the director has set in, Mike Buschjost has begun to think about the hunt ahead.

“I’m going to try to give it all I’ve got those first nine days,” he said. “I feel like that’s more important to me to try to get one killed with a bow. If all else fails, I’ll pull the rifle out, but I’m going to give it full dedication that first nine days of the hunt.

“It means a lot to me to get close to the animals and not shoot them from afar. To me it’s better to get right in their space and make it a one-on-one deal.”

In preparation for October, Buschjost and his sons, ages 13 and 10, headed down to Peck Ranch CA and the surrounding area for a camping and scouting trip. Which of the two boys — both avid bowhunters who have joined their father on elk hunts out west — will accompany their father this year wasn’t immediately determined.

“We’re going to have to rock, paper, scissors to see who gets to tag along,” Buschjost said.

Whichever of the lucky boys it is, he will join his father and the other permit recipients on a close-to-home adventure other Missouri elk hunters can only dream of — for now. And with the adventure, like with all adventures in the outdoors, will come the stories, McGeehan said.

“I can’t imagine the stories that will be told around Christmas of this year when those four citizens and one landowner get to share the experience that they had in harvesting one of the first elk in the state of Missouri.”

About Elk

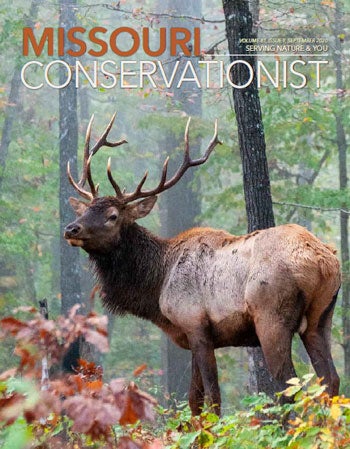

Elk (Cervus elaphus) are the second-largest cervid in North America. Bull elk (males) in Missouri can weigh more than 700 pounds and cows (females) can weigh more than 550 pounds.

The Missouri Elk Partnership

Restoring a sustainable elk population in Missouri is the result of a federal, state, not-for-profit, and landowner partnership. The Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation funded much of the early effort. Nearly half (49 percent) of the elk restoration zone is held in public trust by MDC, the National Park Service, or the U.S. Forest Service. Another 27 percent is private land maintained by the L-A-D Foundation, which works to maintain the property through sustainable forestry and woodland management, while another 3 percent is protected by the Nature Conservancy. The remaining 20 percent is privately owned.

Habitat work done by the elk partners has ensured that the herd has thrived in the elk restoration zone, said MDC Elk and Deer Biologist Aaron Hildreth.

“While an elk can survive perfectly fine in a heavily, almost closed-canopy, timbered environment, the reality is that they want grassy openings,” Hildreth said. “They don’t always get them, but because of a lot of the habitat work that was done prior to elk getting here and most certainly because of the monumental amount of work that has been done by government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and private landowners, that really is what has allowed them to be very happy and stay where they are.”

Driving Tours

For more on elk driving tours, visit short.mdc.mo.gov/ZJJ.

Meet the Hunters

Hunter: Joe Benthall

Age: 37

Location: Mount Vernon

Hunt Experience: 25 years

Hunted Elk Before: No

Hunter: Sam Schultz

Age: 42

Location: Winfield

Hunt Experience: 30 years

Hunted Elk Before: Yes

Hunter: Bill Clark

Age: 78

Location: Van Buren

Hunt Experience: 50+ years

Hunted Elk Before: Yes

Hunter: Michael Buschjost

Age: 40

Location: St. Thomas

Hunt Experience: Most my life

Hunted Elk Before: Yes

Hunter: Gene Guikey

Age: 59

Location: Liberty

Hunt Experience: 50 years

Hunted Elk Before: No

Also In This Issue

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Editor - Angie Daly Morfeld

Associate Editor - Larry Archer

Staff Writer - Bonnie Chasteen

Staff Writer - Heather Feeler

Staff Writer - Kristie Hilgedick

Staff Writer - Joe Jerek

Art Director - Cliff White

Designer - Shawn Carey

Designer - Les Fortenberry

Designer - Marci Porter

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Circulation - Laura Scheuler