If you asked me about monarch butterflies 15 years ago, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you much. It was just several years ago I became more aware of monarch butterflies and milkweeds, the only host plants for monarch caterpillars. My family and I started planting more milkweeds in our backyard and other areas, and my interest in native plants has grown ever since, including native plants for pollinators. Little did I know that I still needed to pay close attention to not only native plants to help attract varieties of pollinators but also other types of host plants that most of us overlook.

The Orange Snake

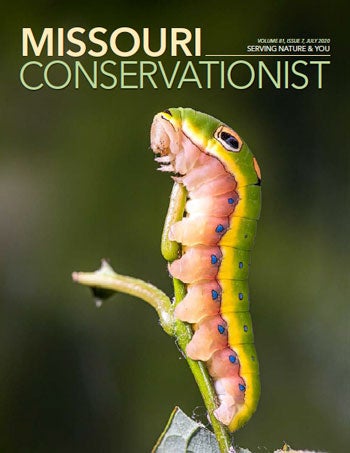

My first encounter with this peculiar caterpillar happened on a late summer evening a couple years ago as I was walking in the woods and was startled by what I thought was an orange snake with large eyes on its bulging head. Upon closer inspection, I discovered that it wasn’t a snake, but was in fact a caterpillar sporting large false eyes on its body.

Even though I was familiar with many different butterfly species, I didn’t know much about this caterpillar. After some quick research, I found that it was a very common species of butterfly in Missouri: a spicebush swallowtail. After my first encounter, it became my new mission to learn more about this mysterious, little-known native butterfly caterpillar of Missouri and the host plant that it needs.

Spicebush and Sassafras

Most people are not aware of this, but butterflies are host plant specific. Just like the monarch butterfly, which depends on milkweeds as a host plant for its caterpillars, the spicebush swallowtail lays eggs exclusively on plants in the Lauraceae family (Magnolia order), which includes spicebush (Lindera bezoin) or sassafras (Sassafras albidum), and depends on these host plants for their survival. Once females lay eggs on a suitable host plant, the caterpillars that hatch from the eggs feed on the plant’s leaves.

The spicebush swallowtail ranges throughout the eastern United States, but is more common in the south. You can find this butterfly in most places in Missouri — except the northwestern part of the state — especially in woodland areas, swamps, stream banks, and residential gardens. In a typical year, two to three broods are produced. Spicebush swallowtails do not migrate south in wintertime. Rather, they overwinter or stay in diapause in the form of a chrysalis and emerge in the following spring season.

Spicebush swallowtails are large black butterflies with iridescent bluish hindwings in females or greenish in males. There are usually light spots near the edge of the forewings and orange spots on the underside of the hindwings. There are three other black swallowtails in Missouri: black swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes), pipevine swallowtail (Battus philenor), and the black form of the female eastern tiger swallowtail (Papilio glaucus).

One-minute Courtship

From April to early September, when there is ample food for the larvae, males stay near nectar plants or host plant sites to find females. When a female appears, the male flies toward her and performs a brief courtship ritual, lasting less than a minute. If the female is receptive to the courtship, mating occurs. After mating, females search out host plants using visual and chemical cues by smelling or tasting them with their forelegs. They then lay eggs on the undersides of the leaves.

Visual Deception, Minimal Detection

- Laying Eggs: Females use both visual and chemical cues when finding host plants on which to oviposit her eggs. After landing on a plant, a female confirms the plant as a host plant by drumming the surface of a leaf with her forelegs.

- The Egg: Eggs are spherical and greenish-white or white in color and transparent. After four to 10 days, larva is visible shortly before hatching. A tiny caterpillar emerges by chewing its way out of the egg. Once emerged, it will consume the shell.

- 1st Instar: First instar caterpillars are small and a brownish/greenish/bronzelike color. The caterpillars typically rest on the center-most vein of a leaf.

- 2nd Instar: Second instar caterpillars start to show other markings and coloration, including the fake eyespots.

- 3rd Instar: Third instar caterpillars look pretty much the same as 2nd, but bigger. The fake eyespots are more visible, though. The color and physical appearance of the caterpillar changes with each molt. The young caterpillar is brown and glossy.

- 4th Instar: As it grows and matures, the caterpillar turns greenish with blue dots. Too big now to pass for a bird dropping, the caterpillar’s green skin allows it to blend in among the plant leaves.

- 5th Instar Green: Spicebush swallowtail caterpillars, bright green with numerous blue spots, have secondary fake eyespots that are yellow. Their bottom half is pinkish. When viewed from a certain angle, they resemble a snake to ward off predators.

The life cycle of the spicebush swallowtail caterpillar is marked by visual deception and hiding from detection. The earlier stages of the caterpillar are camouflaged to look like bird droppings. In later stages caterpillars develop two pairs of false eyespots on their body, which are believed to be a mimicry of either green snakes or tree frogs.

Unlike monarch caterpillars that feed on milkweed incessantly until they reach a chrysalis stage, spicebush caterpillars spend the day in a rolled-up leaf — hiding from predators — and only come out at night to feed on the leaves. They attach threads of silk on either side of the leaf, and as the silk dries, it pulls the leaf around the caterpillar making a perfect shelter. This simple way of rolling a leaf as a shelter is one of the amazing ways that they’ve adapted for survival.

When disturbed, hornlike organs appear behind the caterpillar’s head, and it releases a disagreeable odor, which helps repel some potential predators.

Habitat Help

Even as adapted as spicebush swallowtail caterpillars are, they are still preyed on by many predators, such as spiders, dragonflies, and robber flies. Many birds also eat the adult swallowtail butterfly. However, like many other wildlife, the greatest threats they face come from the loss of habitat, climate change, and lack of host plants.

You can help them by planting their host plants, mainly spicebush, which play a crucial role in their survival. In addition to having the right host plants, plant natives to attract the spicebush swallowtail butterfly, such as milkweed, purple coneflower, and others.

As a nature photographer, I’ve spent many years learning and observing wildlife and nature. But the spicebush caterpillar taught me that nature requires lifetime learning. I also started paying much more attention to host plants and changing the landscape — even on a small scale — to benefit wildlife. I am happy to report that after my first encounter with that spicebush caterpillar, I’ve planted many spicebush plants in my yard and other areas, and I’ve found many caterpillars on those plants.

Even in a small area, we can create a much-needed habitat for pollinators by changing the way we think about our lawn and its usage. A lush green lawn, while giving us an illusion of green space, provides very little use to wildlife, such as butterflies, bees, or other pollinators. We can all make a difference in the natural world. By planting a variety of host and nectar plants for butterflies, you can turn your garden into a much richer habitat that not only satisfies your needs, but also benefits the health of our natural world by attracting many different species of butterflies and bees.

Also In This Issue

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Editor - Angie Daly Morfeld

Associate Editor - Larry Archer

Staff Writer - Bonnie Chasteen

Staff Writer - Heather Feeler

Staff Writer - Kristie Hilgedick

Staff Writer - Joe Jerek

Art Director - Cliff White

Designer - Shawn Carey

Designer - Les Fortenberry

Designer - Marci Porter

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Circulation - Laura Scheuler