By late-summer, Missouri duck hunters are getting antsy for some fall action, even though the waterfowl opener is months away. Sure, the early teal season lures some afield to hone their shotgunning skills and exercise their retrievers, but that only lasts for about two weeks. A handful of hunters have found a more long-term solution to their pre-waterfowl melancholy in the form of snipe and rail hunting.

Yes, the snipe, more specifically the Wilson’s snipe, is an actual game bird, even though many think it’s a mythical creature, hunted with a flashlight and a bag by gullible summer campers.

Many Missourians, including myself, have fallen victim to this practical joke, which goes all the way back to the mid-1800s. Sometimes, the make-believe snipe to be pursued isn’t even a bird, but instead a furry critter from the imagination of the tormentor-in-charge.

This story is about a hunt for real snipe, those sneaky little marshland game birds that use superb camouflage and erratic flight patterns to elude the most experienced hunter. Any discussion of hunting snipe usually includes two other marsh birds, both rails — the sora and the Virginia rail.

Scoping the Quarry

Snipe

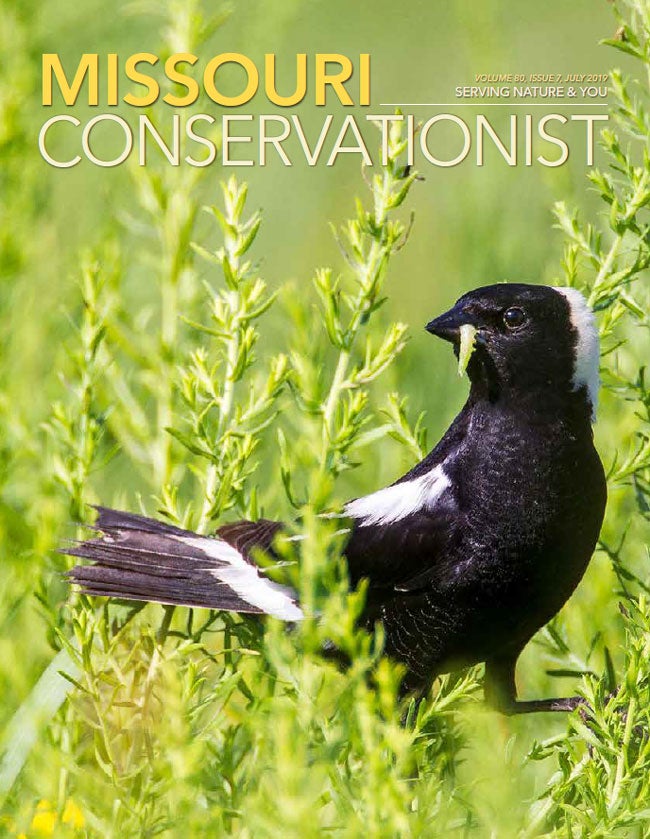

Wilson’s snipe (Gallinago delicata), one of North America’s most widespread shorebirds, is about the size of a killdeer but stouter, and with a very long bill. Although snipe are somewhat similar to other sandpipers, especially the dowitchers, they are easily identified by the stripes along their backs, striped heads, and barred flanks. Their distinct appearance, along with the scraip sound they make when flushed, is important to hunters because they are often found near other nongame shorebirds.

Snipe are most common in Missouri during their spring and fall migrations. They are found statewide during their migration. Hunters look for snipe in moist grassy areas, swamps, shallow marshes, or in drainage ditches. Many hunters seek snipe on the same MDC wetland areas where they hunt waterfowl.

Snipe forage mostly for larval aquatic insects like flies and beetles, but they will also take other invertebrates like earthworms, freshwater shrimp, and small crayfish if they encounter them.

As they poke their bills repeatedly into the mud, probing for invertebrates, their bobbing heads look something like a sewing machine. Their bills have a sensitive, flexible tip that can open to grip food while the rest of the bill remains closed. Snipe are often confused with American woodcock, a closely related species that has a similar shape and bill but different coloration and markings. Also, woodcock are typically found in wooded areas.

Snipe have a zig-zagging flight pattern when flushed, and this makes them a challenge to harvest. Worse, snipe often flush at a great distance because the position of their eyes allows them to detect predators from all directions. This includes hunting dogs, which can’t get close enough to detect the birds by scent.

Sora and Rail

Sora (Porzana carolina) and the Virginia rail (Rallus limicola) typically visit Missouri during their spring and fall migrations. Both have statewide distribution, but the sora is more commonly found.

Adult sora have a stubby, yellow bill and black face. They are quite small, a few inches shorter than snipe. The cheeks and breast are gray, and the belly is barred black and white. The back is dark brown mixed with reddish tan and streaked with white. Immature birds are brown and lack the black face and chest.

Sora live in marshes, swamps, wet pastures, and flooded fields. Preferred habitats have dense vegetation flooded with shallow water. The sora’s strong legs and long toes help it walk on floating vegetation and mud. Its body is compressed side-to-side, making it “thin as a rail,” allowing it to slip easily among emergent marsh vegetation such as cattails. Sora forage on seeds, snails, and aquatic invertebrates. Although seldom seen until they flush, sora are often heard. When entering a marsh, you’re more likely to detect sora by listening for a variety of calls, including ker-wee or sor-ee, wheep, and quink-quink-quink.

The Virginia rail is less common than snipe and sora. Virginia rails have blackish backs with rusty wing patches and a gray face. The long, reddish bill is slightly curved, much different from the sora’s short, yellow bill.

Rounding up the Hunters

When I asked my friend, Lynn Schrader, if he would take me on a snipe hunt, he paused for a few seconds to make sure I wasn’t trying to be funny. Once he realized I was on the level, he gladly accepted. After I explained that I would be carrying a camera instead of a shotgun, Lynn suggested we ask our friend Dave Mayers to join us. Later that day, Mayers, an avid woodcock hunter who had never hunted snipe or rail, replied to my offer as expected: “Sounds fun — I’m in!”

Preparing for the Hunt

We made plans to hunt B.K. Leach Memorial Conservation Area (CA) in Lincoln County soon after the start of the season in early September. Lynn explained that the first hunt might end up as a scouting trip because both snipe and rail are migratory, and their numbers would depend not only on weather conditions at the time of the hunt but moisture on the area as well.

Dave and I had a ton of questions about the hunt, but first and foremost for Dave was whether he should bring his pointing dog, Java. Lynn said that Java would be very helpful, at least for rail hunting, because it is extremely difficult to find a downed sora in dense, flooded vegetation without a dog. But there was a catch involving the preferred vegetation of rails at Leach CA — millet seeds!

Millet, an annual native at Leach, provides excellent cover and food for sora. Unfortunately, the same millet seeds that sora consume often become lodged under the eyelids of hunting dogs. After making two expensive visits to the veterinarian to extract pesky millet seeds from pups, Lynn was reluctant to invite Java along for the hunt.

Dave was initially crestfallen, but his mind quickly went to work, as usual. He would fit Java with goggles customized for canine use and get her used to wearing them a few weeks before the hunt.

Hunting Snipe and Rail

The morning of the hunt finally arrived, and Lynn and Dave began trudging through a field of flooded millet and smartweed at sunrise. Java was in the lead, buried somewhere in the thick vegetation.

It wasn’t long before Java made her first point. A few seconds later, a bird flushed, and Dave bagged his first sora with his 20-gauge over-and-under. We took a moment for high-fives all around and continued our march.

It had been unseasonably warm and dry before the hunt, and we only saw one or two snipe all morning, both flushing at a great distance. At Leach, snipe are often found probing freshly disked, moist-soil areas for invertebrates. We covered all of the disked areas that we could find to no avail. Finally, Lynn and I began making plans to return after the next cold front with a good rain. The rest of the morning would be devoted to sora hunting.

By midmorning, the duo had harvested several sora, but we never saw a Virginia rail. Finally, steaming in the summerlike humidity, we decided to call it quits. Even Java’s goggles fogged up at one point, but, otherwise, they had worked like a charm. We headed back to the truck, happy to have bagged some birds.

A few weeks later, a cold front with rain came during the night, so Lynn and I headed back out the next morning. Our plan was to walk a disked patch of cattails, about 5 acres in size and flooded with sheet water.

We began a few minutes after sunrise and immediately saw a group of six snipe flushing 100 yards out. It was as if they had materialized with the cold rain. We marked some of the singles and headed their way. Lynn missed the first bird, which flushed with the classic, erratic trajectory, apparently zigging just as Lynn’s barrel zagged. The next two birds weren’t as lucky

Managing Snipe and Rail in Missouri

Gary Calvert, wildlife management biologist and Leach CA manager, said he starts early when managing for snipe and rail, well before the teal season. Crews disturb about a third of the area by disking and mowing, and then flood those areas with sheet water for snipe, other shorebirds, and rail.

Typically, they disk areas in moist soil covered with perennial vegetation such as cattails, nut sedge, and bulrush. Disturbing those areas results in the production of native millet, smartweed, and other annuals that provide exceptional food and cover, especially for rails. Snipe frequent the freshly disked areas where they find plenty of moist mud to probe for invertebrates. Each year brings its own set of challenges regarding weather and moisture, Calvert said. Timing is everything, and some years are better than others for snipe and rail hunting.

Getting Started

It’s always wise to scout your wetland conservation area of choice before the season. Don’t hesitate to contact the area manager for suggestions. Schrader recommends the shotgun gauge of your choice, loaded with No. 7 to No. 8 nontoxic shot.

When hunting rail, you’ll need at least a pair of hip boots, but Schrader prefers chest waders to fend off the millet and smartweed seeds that find their way into anything shorter. If you are just hunting snipe, a pair of hip boots or even knee boots will suffice.

Cooking Your Harvest

Snipe have been described as tender and rich in flavor, best prepared medium-rare. I’m sure there are dozens of recipes for snipe, but as with most gamebirds, I prefer to just cook them on the grill over charcoal. Most hunters don’t feel the need to marinate snipe beforehand as they often do with waterfowl. Finding interesting ways to prepare the snipe and rail you harvest will be a bonus to a satisfying outdoor experience.

Hunting snipe requires stamina and shooting skill, but the rewards are satisfying, in the field and at the table.

Don’t Shoot King and Yellow Rails!

Hunters occasionally run across two other rails that are quite uncommon and protected from harvest in Missouri. These are the king rail (Rallus elegans), which is state endangered and much larger than other rails, and the tiny yellow rail (Coturnicops noveboracensis), which shows distinctive white wing patches when flushed.

Know the Seasons and Regulations

Missouri’s snipe season typically runs more than three months. In 2019, opening day is Sept. 1, and the season closes Dec. 16. Hunters can pursue sora and Virginia rail from Sept. 1 through Nov. 9.

Remember, on conservation areas that have managed waterfowl hunts (such as B.K. Leach CA), hunting of wildlife other than waterfowl is prohibited, except in designated areas, from Oct. 15 through the prescribed waterfowl season.

Always consult the Migratory Bird and Waterfowl Hunting Digest for seasons, bag limits, and area requirements for nontoxic shot. Find it at short.mdc.mo.gov/ZpP or wherever hunting permits are sold.

Also In This Issue

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Associate Editor - Larry Archer

Staff Writer - Bonnie Chasteen

Staff Writer - Heather Feeler

Staff Writer - Kristie Hilgedick

Staff Writer - Joe Jerek

Creative Director - Stephanie Thurber

Art Director - Cliff White

Designer - Les Fortenberry

Designer - Marci Porter

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Circulation - Laura Scheuler