Eastern collared lizards prance atop granite boulders on sunny days in southeastern Missouri glades, while in the state’s northwest corner, prairiechickens peck for bugs and hide from predators beneath grasses and wildflowers growing on deep soil.

While geography separates these unique species, conservation gives them something in common. Prairiechickens are endangered and eastern collared lizards are a species of conservation concern. But MDC’s partnerships with private landowners for habitat improvements have expanded the supportive range for both species. Their success or failure signals the prospects for many other prairie- or glade-dwelling plants and animals, too.

Without projects that keep unique habitats, such as rocky glades, in their natural states, “there are several adapted species that won’t thrive,” said Julie Norris, MDC private land conservationist in St. Francois and Iron counties. “One species that comes to mind is the collared lizard. It doesn’t live anywhere but in these glade communities. There’s a lot of sun-loving plants we wouldn’t see, and unique species like the glade grasshopper.”

MDC, in partnership with the USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), assists people who own property with the potential to provide important wildlife habitat. The federal agency offers cost-share opportunities to states under the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) for land management improvements that can help wildlife, and in some cases farm profitability. MDC provides expertise to help landowners plan and implement improvements. The RCPP program pays for expenses, such as native grass seed purchases, hiring contractors to remove unwanted trees, or conducting prescribed burns. Sometimes a landowner plan includes MDC’s Landowner Assistance Program funds or money from other USDA programs that add to habitat benefits.

Under the RCPP grants, landowners receive assistance with habitat improvements that help all wildlife but also specifically benefit species that are endangered, rare, or dwindling. Programs can be tailored to fit a property owner’s goals and the specific habitat needs. Owners have two or three years to complete the practices, so work can be done in stages as needed.

Some landowners initially seek better deer and turkey habitat, “but then they discover the value of restoring habitat for the outlying species, too,” said Roger Frazier, MDC priority habitat coordinator.

Restoring Glades Among the Granite

The granite boulders and outcrops topping hills in the St. Francois Knobs region originated as volcanic eruptions almost 1.5 billion years ago. The weathering of rock and accumulated dust and organic matter over millenniums left thin soils in cracks, crevices, and on terraces where unique plants grow on hilltops or hillside glades. Further down the slopes, deeper soils support trees, originally growing in scattered patterns alongside native grasses and wildflowers. Eastern collared lizards prefer life among the stones. Deer and turkeys like the open woodlands. Historically, wildfire kept trees and shrubs from dominating the glades and woodlands, preserving the plant diversity that helps wildlife.

Human settlement in the 1800s changed the ecological pattern by suppressing fire. This allowed red cedar trees to invade the glades in thick groves. Red cedars are native and have their benefits for people and wildlife. But they can be harmfully invasive to glades and prairies by hoarding moisture and blocking sunlight, thus choking out other species.

To restore balance, MDC connects landowners with RCPP financial assistance from NRCS under the Restoring Glade and Woodland Communities for Threatened Species program. Landowners in Carter, Iron, Madison, Reynolds, Ripley, Shannon, Ste. Genevieve, St. Francois, and Wayne counties were eligible for RCPP assistance for habitat improvement projects. The glade and woodland program also addressed karst habitat needs in Perry County.

Putting Grants to Work

Norris studied aerial photos and habitat maps for St. Francois County to find potential glade restoration sites. She left flyers about the RCPP program in mailboxes. Her phone soon began ringing.

Terry O’Brien sought help for about 160 acres, mostly woodland, and 15 acres of glades at his Shanahill Farm near Park Hills. Norris helped him receive RCPP cost-share money to pay contractors to cut cedar trees off the glades, conduct prescribed burns, and thin trees in the woodlands. Plus, he’s planning a wildflower plot with financial assistance from a separate program to benefit pollinators, like bees and butterflies. He left several dogwood and redbud trees uncut among the oaks and watches them bloom in spring. Native warm-season prairie grasses, like big bluestem, appear in summer. A native plant seed bank lingering in the soil from before the cedar invasion came to life when trees were cut and leaf litter burned away.

“It looks great, unbelievably great, a remarkable improvement,” O’Brien said. “It’s remarkable what prescribed burning can do. The wildflowers have come back. There are different flowers that I’ve never seen before. It’s opened up and the view improved immensely.”

He never saw eastern collared lizards on his glades before the cedars were removed. The lizards will not move to an overgrown glade. But they will repopulate areas with large rocks for them to hide under and where renewed grasses and wildflowers support insects for them to eat.

“They’re everywhere now,” O’Brien said of the foot-long lizards with assorted tan, lime-green, and orange colors. “They’re fabulous little guys.”

For Wildlife and Wildflowers

Ken Allen of Farmington witnessed a surge in wildlife and wildflowers on his small acreage after getting assistance through the RCPP program. Norris visited the farm, and they laid out a plan for changes to the overcrowded woodland with rocky patches.

“There’s a lot of granite out here,” Allen said.

Under the program, a contractor built fire lanes. Timber was thinned and cedar trees were removed. A small pond to provide water for wildlife was built. A contractor conducted a prescribed burn. Costs for habitat work vary according to practices, contractor prices, and acreages treated. The percentage of costs covered can vary but can range up to 90 percent paid by RCPP. For Allen, the RCPP program provided $14,000 for improvements on 30 acres, and he paid $2,000. The fire lanes he now maintains also double as hiking trails.

“The wildflowers sprang up, and grasses came up we’d never seen before,” Allen said. “Doves have moved in. We’ve noticed the rabbit population increased.”

Deer and wild turkeys also seem more numerous, he said. At night, they sit on their front porch and listen to frogs croaking in the pond. The changes required extensive tree thinning to open the tree canopy. Norris helped them pick what trees to take and which to leave.

“My wife was not totally on board,” Allen said. “She was upset that we were taking her forest and she was afraid the wildlife might not come back. But she’s really happy with the outcome now.”

Their project, however, is contributing to a far broader wildlife boost in the St. Francois Knobs. The Allen farm is near six other properties where landowners have signed up for RCPP or MDC’s Landowner Assistance program to restore open glades and woodlands. One neighbor completed cedar removal from 7 acres of glades and hosted a 40-acre prescribed burn. Eastern collared lizards soon increased in the newly opened habitat.

“This is a neat representation of how smaller acreage landowners are able to do work that can potentially get big results over time by working on farms that are in close proximity,” Norris said.

Helping Prairie-Chickens Make a Stand

The Wisconsin glacier pushing south and then receding 20,000 to 14,000 years ago, along with wind-blown silt from glacial melt, created a loess soil base that lush prairies and woodlands eventually covered in loamy, nutrient-rich topsoil in northwest Missouri. That soil now produces cattle and crops that help feed the world. But in the rolling hills of Harrison and neighboring counties, remnant or restored native grasslands are also a last stronghold for endangered prairie-chickens in Missouri.

MDC connects ranchers in the area with RCPP projects, a key component in helping one of the state’s last prairie-chicken flocks survive. Statewide, funds from the NRCS Regional Grassland Bird and Grazing Land Enhancement Initiative are authorized for parts of 40 counties in Missouri’s cattle country. But that program is especially important in helping property owners improve prairiechicken habitat in MDC’s Grand River Grasslands priority geography.

Less than one-tenth of one percent of Missouri’s original prairie remains in scattered remnants, and prairie-chickens have dwindled to less than 50 birds in two widely separate flocks. This spring, 33 of those birds were counted in Harrison County. Most were on The Nature Conservancy’s Dunn Ranch Prairie, their established haven in the heart of the Grand River Grasslands.

But Kendall Coleman, MDC private lands conservationist, also found prairie-chickens this spring using a lek, or mating ground, on a private farm. The RCPP program has paid for tree cutting and native grass establishment in that area. In the past, biologists have tracked nesting and broods being raised on a cooperator’s land.

“It makes me feel a little better about prairie-chickens, that this might actually work for them,” Coleman said.

He’s currently working with 26 landowners who are planning or have implemented improvements. Coleman developed an innovative RCPP program for his area that increases the percentage of cost-share assistance when landowners add conservation practices to their project. They can receive up to 90 percent cost-share match if they take a holistic approach that incorporates all four practices of tree or brush removal, planting native warm-season grasses, protecting streams, and resting pastures. Not all practices fit each farm. But for example, cost share provides $358 per acre for native grass establishment, or $680 when all four practices are used. Conservation practices must meet NRCS standards. But the program has flexibility to be an affordable way to meet a landowner’s goals and help wildlife. That flexibility includes a few years to complete the changes.

Mingling Prairie-Chickens with Cattle

Rancher Robin Frank of Eagleville is happy to help wildlife on his pastures near Dunn Ranch. But his business is raising and grazing cattle, and he likes that enhancing grasslands has helped his ranch’s profitability. The conception rate for his cows producing calves went up when he began letting them graze in late summer on native warm-season grasses. RCPP financial assistance helped him with the cost of replacing fescue with native grasses in those pastures.

“The conception rates are 10, 15, or even 20 percent better on native grass,” Frank said. “They just do better on that warm-season grass.”

The Frank family has also used the RCPP or related programs to clear unwanted trees. Those trees inhibit prairie-chicken movement across the landscape, but they also shade out grass. One example is a program that helped pay a contractor to clear one hillside acreage that was totally brush covered.

“The net result for me was we have more open land for grazing cattle, which is what we do,” Frank said. “The net cost to me was $100.”

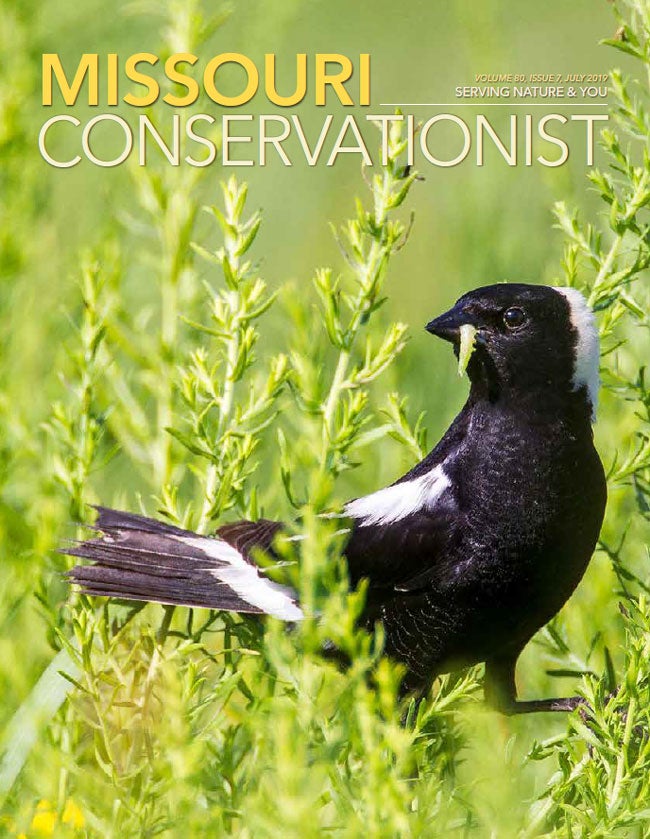

Coleman has helped Frank install two gravel stream crossings and fence cattle away from an upland creek. Protecting aquatic species, such as endangered Topeka shiners reintroduced to the Grand River Grasslands, is among the objectives. The Franks plan to convert more nonnative fescue to native warm-season prairie grasses. Biologists studying grassland bird populations have noticed good numbers of songbirds, such as bobolinks, meadowlarks, and grasshopper sparrows, on the Frank farm. Those birds are in a decline in many regions. What helps the prairie-chicken helps other birds, too.

The ranch currently doesn’t host a spring lek, Frank said, “but we see prairie-chickens on our place all the time.”

Other landowners in the area are utilizing similar programs to restore grassland ecological functions, which is what prairie-chickens and other prairie species need — several thousand acres with supportive grasslands that are interconnected across the landscape.

MDC expertise and programs like RCPP are making habitat work affordable and effective.

“The incentives interest landowners in doing things that have been overlooked in the past,” Coleman said. “Our ultimate hope is that they like it, that it’s profitable. We’re wanting this to be a partnership that’s mutually beneficial for landowners and wildlife.”

Habitat Improvements for Your Land

MDC’s private land conservationists can connect property owners with a variety of state and federal cost-share programs that provide financial assistance for habitat enhancement or restoration for grasslands, woodlands, forests, and streams. For more information, call your local MDC office or visit mdc.mo.gov/property.

Also In This Issue

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Associate Editor - Larry Archer

Staff Writer - Bonnie Chasteen

Staff Writer - Heather Feeler

Staff Writer - Kristie Hilgedick

Staff Writer - Joe Jerek

Creative Director - Stephanie Thurber

Art Director - Cliff White

Designer - Les Fortenberry

Designer - Marci Porter

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Circulation - Laura Scheuler