For those of us who have grown up in Missouri, especially in the past few decades, we’ve had the privilege of enjoying conservation at its finest — healthy forests to hike, abundant wildlife to watch or hunt, and ample fish to catch. We have a beautiful state with immense outdoor opportunities. While we’re lucky to live here, these rich conservation resources have nothing to do with luck. It’s because citizens have led the way, year after year, for a better conservation future.

American journalist and author Norman Cousins said history is a vast early warning system. Missouri conservation history is no different.

In the early 1900s, much of the state’s natural resources had been destroyed, pilfered, or used up. Entire forests were cut down for building materials or fuel, leaving only a wasteland of rocky soil. Wildlife were killed in mass numbers and brought by wagonloads to city markets. Fish were dying in streams eroded by timbering and wildfire. It was a dark time on the Missouri landscape, but a new day was dawning.

Citizens came together in 1936 to lead the charge and voted to establish the Conservation Commission to protect the forests, fish, and wildlife in the state. While less highlighted in history books, women played a major role in this turn toward conservation, including publically endorsing the amendment around the state before the vote at the Federation of Women’s Clubs and local garden clubs. They also strongly cast their vote during the election, and the Department was established in the Missouri Constitution by more than a 2-to-1 vote.

But the work didn’t stop there. In the Department’s early days, many influential people, such as E. Sydney Stephens, Aldo Leopold, and I.T. Bode, were making a difference. But one woman played a significant, behind-the-scenes role from the very beginning. Bettye Hornbuckle served as the Department secretary to the Conservation Commission and then as the Director’s administrative assistant, and she was a steadfast figure in the prominent decisions of the first two decades of the Department’s history.

While Hornbuckle served on staff with the Department, there were many others making a difference who served strictly as volunteers. In 1976, Doris “Dink” Keefe, a mother and homemaker, led a large group of volunteers for a petition drive to place a conservation sales tax on the Missouri ballot to establish dedicated funding for forests, fish, and wildlife. She volunteered for a full year, unpaid, and meticulously checked thousands of signatures from nine congressional districts. Her tireless efforts, and those of many others, paid off when the one-eighth-cent sales tax for conservation passed in November 1976. It created the critical dedicated funding needed to ensure the success of conservation in Missouri for future generations. It also paved the way for other women of all ages to continue contributing to conservation in their own unique way.

The Scientist

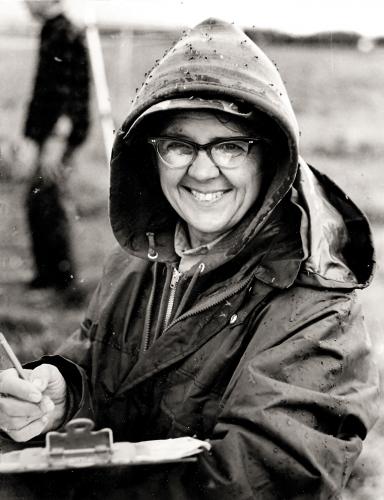

In 2014, Elizabeth “Libby” Schwartz was inducted into the Missouri Conservation Hall of Fame and became part of an elite group of Missourians honored for their outstanding dedication to conservation in Missouri. Schwartz began her career teaching biology classes at the University of Missouri-Columbia, where she met her future husband and biologist, Charles W. Schwartz.

They would become an inseparable team and two of the nation’s foremost experts on American wildlife. Both worked for the Department for more than 30 years, conducting landmark field research together on prairie chickens and box turtles. Research was not the only thing the couple did well together. Charles and Libby spent weeks at a time in the field capturing unique wildlife photography and footage for Department films, many of which won national and international awards. Their movie, Bobwhite Through the Year, won the CONI Grand Medal at the International Sports Film Festival in Rome in 1952.

The Schwartzes also authored and illustrated many scientific articles and books, such as The Wild Mammals of Missouri, which was first published in 1959, and which is still used in university courses to this day. They also wrote and illustrated a series of children’s books. After Charles’ death in 1991, Libby continued working on their final collaborative book, About Mammals and How They Live, which was a companion book to their original The Wild Mammals of Missouri.

Libby’s love of learning, especially about wildlife, continued all her life. She took college classes well into her 80s and even traveled to Alaska to see for herself the melting glaciers she was reading about in the news. Although she passed away in 2013, her talent and contribution to conservation set the standard for future conservationists, both professionally and personally.

At their Department retirement in 1981, they were honored with these words: “No two individuals have contributed more than Charles and Libby Schwartz to the success of Missouri conservation — past, present, and future.”

The Landowner

Although Pat Jones grew up in St. Louis, she developed a love of the outdoors at an early age from her parents. Her father would put his canoe on the train and then get off at a river stop to float down the river, often camping overnight at a gravel bar. He eventually would buy some land near Eureka so his young family could also enjoy the weekends and summers on the land. It was an introduction to the outdoors Jones remembers fondly.

“If you didn’t get out there on the weekends to the shack, which is what we called the place, it was a lost weekend,” said Jones. “It was the only place you really got together as a family.”

Jones would eventually marry Ted Jones, a young man from St. Louis, who also had a love of his family farm in Callaway County. Ted’s father traded federal land bank bonds for the rambling farm in the 1930s and, although it was overgrown and weedy, young Ted saw potential.

When he was 10 years old, he planted a row of pin oak trees he received from Arbor Day to begin a lifelong restoration of the land.

Just as Ted gave his company, Edward Jones Investing, to his employees to carry on the legacy, Pat also wanted to ensure their land had the same long-term impact. She had the idea to donate the land to the Department to form Prairie Fork Conservation Area and create a partnership between the Department, the University of Missouri School of Natural Resources, and the Missouri Prairie Foundation for ongoing natural resource education, natural community restoration, and environmental research.

“If you want to keep doing what you’re doing into the future, you need to give it to people who can keep moving it forward,” said Jones.

The 900-acre conservation area provides educational opportunities for school-age children and for ongoing research on soil, water, and wildlife. It is a busy place. Last spring, more than 3,000 children, including elementary, secondary, and college-age students, visited Prairie Fork. The area also hosts events for Future Farmers of America, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, and the Conservation Careers Academy, which allows high school students to learn about different careers in conservation. Prairie restoration is an ongoing activity, including restoring about 30 to 40 acres each year. There are also two or three research projects — such as groundwater quality or box turtle tracking — underway simultaneously.

All the activity is something Jones loves to see, especially since she gets to personally witness the next generation getting excited about exploring the land, just like she did as a kid. She greets them all with this message, which is engraved on a stone wall on the property: Learn, Get Dirty, and Have Fun!!

“Those three things are all so important,” said Jones. “I want kids to come out and be exposed to the land. My favorite part is seeing that happen.”

The Volunteer

Because Laura Toombs is a full-time shop owner at the Lake of the Ozarks and mother to a busy teenager, you would think she wouldn’t have any extra time on her hands. But she makes time each week to volunteer for something she loves and believes in — conservation in her community!

When Toombs moved to the Lake a few years ago, she wanted to find a way to volunteer that would also allow her to get outside in nature. She signed up to take a Missouri Master Naturalist training class with the Department and the University of Missouri Extension through the Lake Master Naturalist chapter. The training provides volunteers an opportunity to learn more about natural resources in their area through science-based education and then to volunteer at local events, educational demonstrations, and stewardship projects. It was a wonderful experience for Toombs.

“You go once a week to the class and learn from the best people in the Department on so many subjects,” said Toombs. “It is a great growing experience, and you get to meet some great new friends with common interests.”

As part of her Master Naturalist volunteer work, Toombs was interested in starting a conservation kids club at the Lake, modeled after the one she had volunteered at several years ago at the Department’s Springfield Conservation Nature Center. With no nature center at the Lake, Toombs felt there was a need for an organized kids club focused on local conservation. With the help of Department staff in the Camdenton office, Toombs was part of the group to launch Conservation Kids Club, a monthly offering for third- to fifth-graders at the Lake to explore conservation, Missouri wildlife, and to have fun.

“It is important for kids to be aware of the outdoors where they live,” said Toombs. “If you don’t learn about what is out there, it is no great loss when you lose that.” Toombs reflects on her own childhood that set her love of the outdoors in motion. Her father was an avid fisherman and her mother a bird watcher. They were always doing something outside as a family, she said.

“It was a constant influence, always something to do, always something to see, and if you didn’t want to fish trout that day, you could always stay by the bank and play,” said Toombs. “But it was never an option to not be outside.”

Toombs speaks highly of her parents’ influence on her outdoor education, but also credits the work of the Department and staff for helping guide her adult education.

“We are so lucky to have the Conservation Department in Missouri because it isn’t like this in other states,” she said. “Department employees act as a mentor to volunteers, and they are always right there when you need something.”

Even though she is busy, her goal with volunteering is to keep paying it forward to help others love the outdoors as much as she does. She has given her time, true, but she has gained so much more in knowledge, meeting people, and feeling good about the work she is doing, she said. Her advice to others: “Get out there in it! If you are lucky enough to have a Master Naturalist chapter near you, get involved. It deepens your experience of the outdoors and it is fun.”

For more information on how you can get involved in conservation, including as a private landowner, volunteer, or to explore a career in conservation, visit mdc.mo.gov.

Women in Missouri Conservation History

1936, November 3

Missourians, including women and men, vote to establish the Missouri Department of Conservation in the Missouri Constitution by more than two to one in favor. Prior to the vote, many prominent women’s groups, including local garden clubs and Federation of Women’s Clubs, publically endorse the amendment.

1937

Department of Conservation is established. Bettye Hornbuckle plays a major role in early Department efforts, serving the Department as secretary to the Conservation Commission and as the Director’s administrative assistant. She continues in that role until her retirement in 1954.

1940, March 4

Commission hires Faith Watkins as first female employee assigned to direct a program, including youth and women’s programs.

1948

Virginia Dunlap is the first female awarded the Master Conservationist award.

1975

Jill Cooper is the first female conservation agent.

1976

Doris J. “Dink” Keefe, conservation volunteer, led a group of volunteers for a petition to place a Conservation Sales Tax on the Missouri ballot. The ballot initiative is supported by Missourians and establishes dedicated fundingfor forests, fish, and wildlife.

1993

Anita B. Gorman is the first woman appointed to serve on the Conservation Commission. Gorman also chaired efforts to fund half the cost of the Discovery Center, later named the Anita B. Gorman Conservation Discovery Center, in Kansas City.

1996

Ann Kutscher, past president of Mid-Mo Conservation Society, becomes first female president of the Conservation Federation of Missouri.

2001

Cynthia Metcalfe is appointed to the Conservation Commission. As commissioner, she promoted land and program management to ensure that all Missourians, especially children, may enjoy nature as well.

2007

With deep roots in both conservation and agriculture, Becky Plattner is appointed to the Conservation Commission. She is also a lifetime member of the National Wildlife Conservation Federation.

2012

Department hires Kelly Straka as the first state wildlife veterinarian.

2014

Marilynn J. Bradford is currently serving on the Conservation

Commission. Her interest is in expanding outdoor opportunities for women and children.

Also In This Issue

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Art Director - Cliff White

Staff Writer/Editor - Bonnie Chasteen

Staff Writer - Heather Feeler

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Designer - Stephanie Thurber

Circulation - Laura Scheuler