The sharp-shinned hawk has short, rounded wings and a long, square-tipped tail with an off-white terminal band. Blue-gray above, rusty horizontal barring below. Head small, appearing shorter in flight than the head of Cooper’s hawk, whose head projects noticeably past the leading edge of the wings; head color is the same as the nape and back. Immatures have thick red-brown streaks below and are brown above. In flight, sharp-shinned hawks alternate flapping and sailing and may be more buffeted by the wind than Cooper’s hawks.

Key identifiers:

- Head smaller than that of a Cooper's hawk

- Tail square-tipped

- In adults, dark cap and nape appear continuous

Similar species: Their size and shape separates sharp-shinned and Cooper’s hawks from other raptors: both have short, rounded wings and long, narrow, rudderlike tails. Unlike red-tailed hawks and other buteos, they don’t soar in circles high in the air. It can be difficult to tell the sharp-shinned from the Cooper’s, however. In addition to its larger head, the Cooper’s hawk has a rounded (not squared) tail, with outer feathers appearing shorter than the middle ones, apparent when the tail is folded as well as in flight. On Cooper’s adults, the dark cap contrasts with the pale nape, while adult sharp-shins have a dark cap and nape. Consider their habitat preferences, too (see below).

Length: 11–14 inches; wingspan 22–28 inches.

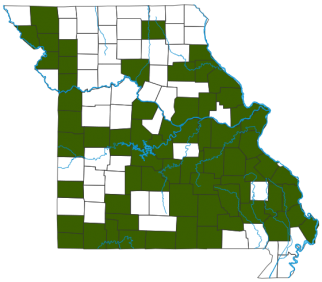

Statewide.

Habitat and Conservation

Usually seen in hedgerows, along tree lines, and occasionally at bird feeders, as they hunt for birds to eat. Frequently seen foraging along hedgerows and brush-entangled fencerows; as summer residents they are typically seen in forested landscapes, usually nests in shortleaf pine plantations. In winter resident, they are most often seen in the Ozarks.

Accipiters are most abundant during the spring and fall when songbirds are migrating. They follow, migrating with their prey during the spring and fall, and spend the winter on the songbirds’ wintering ground. As a species requiring dense, wild areas for breeding, the sharp-shinned hawk declines in places where its habitats are disrupted.

Sharp-shinned hawks are more strongly associated with wild areas than Cooper’s, which are more frequently seen in backyards. Sharp-shins may show up in neighborhoods in winter, however, to stalk birds at feeders. Sometimes the first sign that a sharp-shinned or Cooper’s hawk is nearby is when all the birds in an area are suddenly silent and hidden; they seek cover in dense bushes when one gives a warning call.

Food

The sharp-shinned hawk, plus the Cooper’s hawk and northern goshawk, are accipiters; they are the true “chicken hawks.” Fast, agile fliers, they can pursue and catch other birds in flight. They may also eat small mammals such as squirrels and mice. Accipiters may visit bird feeders in winter to prey on the birds attracted to the food. They chase their prey through the branches of trees and shrubs with great speed and accuracy. They fly swiftly, flashing from the cover of trees and shrubs, surprising their prey.

Status

Uncommon migrant statewide; rare summer resident (in the south); uncommon winter resident. A Missouri species of conservation concern.

Life Cycle

Sharp-shins build their nests in areas with abundant songbirds, which they feed to their nestlings. Nests are usually built in pines or other conifers, usually positioned high in a tree but sheltered by higher forest branches. They are shallow platforms 1–2 feet wide and half a foot deep, built of dead twigs. A clutch comprises 3–8 eggs, which are incubated 30–35 days. After hatching, they remain at the nest 21–28 days, but are dependent on the parents for several more weeks, as they gradually learn to hunt for themselves. There is only one brood a year. Sharp-shinned hawks can live to be at least 12 years old.

Human Connections

People used to kill sharp-shinned and Cooper’s hawks because they were deemed “destroyers” of birds, including, sometimes, free-roaming juvenile poultry. Today, we have a much more balanced view, but it can still be upsetting when an accipiter lingers around a birdfeeder, stalking songbirds. If this happens in your backyard, try removing your feeders for a few weeks; the hawk will move somewhere else.

Sharp-shins are one of the species that declined in the middle 1900s due to widespread DDT use. Some still have high levels of this pesticide, apparently because they prey on birds in South America, where DDT is still legal.

Ecosystem Connections

As with most predators, accipiters are probably naturally rare. Generally speaking, the more abundant the prey, the more abundant the predators, and hopefully vice versa; an abundance of accipiters is usually a sign of good health for other bird populations in general.

The possible presence of hawks or other predators helps explain why songbirds are so nervously vigilant, with such quick reflexes.

About 350 species of birds are likely to be seen in Missouri, though nearly 400 have been recorded within our borders. Most people know a bird when they see one — it has feathers, wings, and a bill. Birds are warm-blooded, and most species can fly. Many migrate hundreds or thousands of miles. Birds lay hard-shelled eggs (often in a nest), and the parents care for the young. Many communicate with songs and calls.