The great egret is an unmistakable large white heron with a large yellow bill and black legs and feet. During breeding season, great egrets develop long, graceful plumes on their backs, and an exposed patch of facial skin turns bright green. The voice of a great egret is similar to that of the great blue heron but is lower and less resonant.

Key identifiers:

- A white heron

- Yellow bill

- Black legs and feet

- Large, for a heron

Similar species: Missouri’s four white herons — great egret, snowy egret, little blue heron (immature), and cattle egret — are all fairly common within their appropriate habitats. They may all be present in the same foraging flocks at floodplain pools or appear singly at a lake or farm pond. The great egret is easily distinguished from the others by its large yellow bill and dark legs, a combination no other heron in Missouri has, except perhaps for an immature cattle egret, which may have blackish legs. Adult cattle egrets usually are easily separated from great egrets by their small size, yellow bill, and yellow legs.

Length: 39 inches; wingspan: 51 inches. Slightly smaller than a great blue heron.

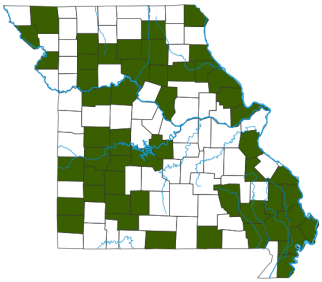

Statewide.

Habitat and Conservation

Forages in marshes, ponds, ditches, and lakes. Some of the best locations to see large groups of herons foraging on floodplain wetlands include Eagle Bluffs, Ted Shanks, and Schell-Osage Conservation Areas and Squaw Creek, Mark Twain, and Mingo National Wildlife Refuges. River sandbars and shallow backwaters are also good places to see herons. When this species was hunted nearly into extinction, a popular groundswell for conservation saved it and, as public awareness grew, many, many other species.

Food

Like most other large herons, great egrets stalk smoothly through shallow water, or just stand still, looking intently for prey below — small fish, frogs and other amphibians, crayfish, and large insects. A swift, precision jab with the bill catches the prey, which is flipped around, if necessary, and swallowed whole.

Status

A Missouri species of conservation concern.

As a summer breeding resident, uncommon but local; as a summer (nonbreeding) visitor, common; as a winter visitor, accidental. As a local and rare summer breeding resident in mixed heron colonies, look for it mainly in the Bootheel’s Mississippi Lowlands. After the end of the breeding season, young and adult great egrets disperse from nesting colonies and may be observed statewide.

Life Cycle

Great egrets are mostly present in Missouri late March through mid-November, with numbers peaking the first half of May and from mid-July through mid-October. Many heron species in Missouri crowd into colonies in the spring to build their nests and raise their young. Sometimes a few pairs of great egrets appear in breeding colonies of great blue herons. Nests are made of sticks and twigs; the nests are large — up to a yard across and a foot deep. They are often built in trees above water. A clutch has up to 6 eggs, which are incubated for 21–27 days; after hatching the young stay at the nest for 21–25 days. Great egrets can live to be at least 22 years old.

Human Connections

If you find a heron colony, keep your distance: alarmed herons may abandon their nests or destroy them in their flight; young may fall into the water and drown; fleeing birds may collide with branches or each other and break their wings. Also, entering heron colonies (or other large colonies of birds) increases your risk of contracting histoplasmosis, a serious respiratory disease caused by the airborne spores of a fungus common on bird droppings. Use binoculars or a telescope.

Ecosystem Connections

Great egrets were overhunted in the 1800s because of a huge market demand for their graceful white breeding-plumage feathers, which were used to decorate hats. Hunters swarmed the countryside, killing vast numbers of egrets, especially when they were concentrated in nesting colonies, devotedly trying to rear their young. As their numbers declined, the price of their scalps increased. The birds nearly went extinct. This is when the National Audubon Society and many other conservation organizations formed, demanding lawmakers and fashion leaders to take action to save these and many other species. Their movement continues today, as conservationists seek to protect not only individual species but the habitat systems on which they depend.

About 350 species of birds are likely to be seen in Missouri, though nearly 400 have been recorded within our borders. Most people know a bird when they see one — it has feathers, wings, and a bill. Birds are warm-blooded, and most species can fly. Many migrate hundreds or thousands of miles. Birds lay hard-shelled eggs (often in a nest), and the parents care for the young. Many communicate with songs and calls.