Dickcissel adult male upperparts are gray-brown with dark streaks; the shoulders are a rich chestnut. There is a white eye ring, a yellow eyebrow and moustachial streak, and a gray cheek. Underparts are white, with a yellow breast and, in breeding plumage, a black “bib” on lower throat and upper breast. Females have hints of yellow on the breast and eyebrow, and less obvious chestnut on shoulders. Song is a harsh dick-dick-dickcissel. The call given in flight frequently is a buzzy, electric bzzzzt.

Similar species: Eastern and western meadowlarks, though similar in coloration and found in similar habitats, are larger, chunkier, with longer legs. They are members of the blackbird family, with longer, pointier bills; dickcissels are smaller and sparrow- or finch-like. The songs are different, too. Sometimes also confused with house (English) sparrows.

Length: 6¼ inches (tip of bill to tip of tail).

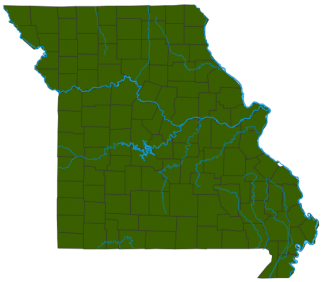

Statewide. Abundant in the Glaciated and Osage Plains and in the Mississippi Lowlands. In some years they are common in the larger fields in the Ozark region.

Habitat and Conservation

Native to prairies and other grasslands, but it has adapted to farmland, cereal grain fields, weedy fields, alfalfa fields, hay fields, and other agricultural habitats. In some years it may be very abundant in a certain field and absent the next year. Many pairs may nest in one area and yet none might occupy another, equivalent field. A few individuals may linger late into the fall or appear at bird feeders.

Food

Dickcissels forage near the ground for insects and seeds in weedy fields, grasslands, prairies, and cereal grain fields.

Status

Common resident; casual winter resident. Globally, they declined some 35 percent between 1966 and 1994. Apparently some of that decline was caused in North America, by habitat loss and fragmentation and when harvest equipment destroys nests each year. But where they winter in Central and South America, large flocks of dickcissels eat from crop fields where native grasslands used to be. Many farmers there protect their crops with noisemakers, but in desperation, some may employ lethal methods.

Life Cycle

Cup nests are built of grass and weed stems and lined with finer materials, in grasses or sapling trees a little above the ground. A clutch comprises 3–6 eggs. Upon hatching, the young are helpless. Breeding range is most of the Central United States. In August and September, they begin to form large flocks and migrate south from Missouri. They are mostly gone by mid-October. They pass through Central America and on to northern South America for winter. They return here in late April and May.

Human Connections

Migratory birds require safe habitat everywhere they travel. The conflict between dickcissels and Central American farmers is serious. People can find viable solutions without devastating this bird species. Stay educated, and support solutions that work for everyone, including wildlife.

Ecosystem Connections

During fall migration, dickcissels form flocks of thousands, and winter roosts can include millions. This species is known for its unpredictable patterns, being numerous in a place some years, and absent in others. The environmental impact of so many birds is offset by their irregular appearance.

Where to See Species

About 350 species of birds are likely to be seen in Missouri, though nearly 400 have been recorded within our borders. Most people know a bird when they see one — it has feathers, wings, and a bill. Birds are warm-blooded, and most species can fly. Many migrate hundreds or thousands of miles. Birds lay hard-shelled eggs (often in a nest), and the parents care for the young. Many communicate with songs and calls.