The belted kingfisher's big head, large bill, short tail, and stocky, top-heavy shape is distinctive. Adult males and females have slate-blue upperparts and breast band, and a white collar and underparts. The female has a rusty band on the belly (this is one of the unusual cases where the female bird is more colorful than the male). The bill is large and straight, and the crest is ragged. The voice is a loud, nonmusical rattle.

Similar species: The blue jay could possibly be confused with the kingfisher, but the body shape and behaviors are quite different. To see some different kingfisher species in the United States, visit southern Texas, where Central American species have their northern limit.

Length: 13 inches (tip of bill to tip of tail); a little larger than a rock pigeon.

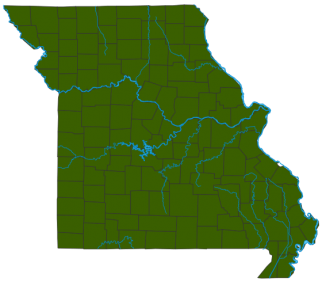

Statewide.

Habitat and Conservation

Often, you hear the rattling call before you spy the bird. Uncommon migrant foraging for small fish and other small animals in rivers, streams, ponds, and lakes. Uncommon summer resident nesting in areas with steep stream banks of soil suitable for digging their nest burrows. Uncommon winter resident in southern Missouri, with only a few individuals staying in the northern section during especially mild winters. Belted kingfishers hover or perch when they forage over water and dive into the water to catch their prey.

Food

Belted kingfishers hover over a pond or lake and plunge headfirst into the water to capture prey seen from above. The small fish is taken to a nearby perch, beaten against the branch, flipped into the air, and swallowed headfirst. It can take a while to swallow a large fish completely. Kingfishers also eat crayfish, frogs, toads, snakes, turtles, insects, young birds, mice, and even fruits. Parents train their young how to dive by dropping food into the water below their perch.

Status

Uncommon summer resident. As winter resident, uncommon in southern Missouri, rare in the north. They were formerly persecuted as fish killers, but hunting them is now outlawed. Populations are declining steeply continent-wide (approximately 46 percent since the middle 1960s). They do not tolerate frequent human disturbance, and their presence in an area often is related to availability of appropriate vertical earthen bank sites for nest burrows.

Life Cycle

Not many birds burrow into the ground, but this is one. Kingfishers excavate burrows where there is a vertical stream bank or pond edge made of loamy sand, generally near good fishing areas. The burrow extends 3–6 feet into the bank at a slight uphill slope. Nests are in a chamber at the end of the tunnel. Clutches comprise 5–8 eggs, which are incubated 22–24 days. Helpless upon hatching, the young can leave the nest in less than a month. There are one or two broods a year.

Human Connections

Kingfisher beer from India has as its mascot the common kingfisher, widespread in Eurasia and north Africa, a colorful, sparrow-sized bird in a different kingfisher family. The Australian laughing kookaburra is in a third kingfisher family. Kingfishers play many roles in ancient lore.

Ecosystem Connections

As visual predators, kingfishers require water clear enough for them to see fish swimming below, and it can’t be iced over, either. Several predators eat kingfishers, such as hawks that can catch them in flight, and mammals and snakes, which can catch them and their young and eggs in their burrows.

About 350 species of birds are likely to be seen in Missouri, though nearly 400 have been recorded within our borders. Most people know a bird when they see one — it has feathers, wings, and a bill. Birds are warm-blooded, and most species can fly. Many migrate hundreds or thousands of miles. Birds lay hard-shelled eggs (often in a nest), and the parents care for the young. Many communicate with songs and calls.