In a few weeks, sports fans will cheer for their favorite football team to win the Super Bowl. Many animals form teams, too. But they don’t do it to win ballgames. Critters team up to build shelters, find food, and stay alive.

Safety in Numbers

A flock of blackbirds smudges the sky like a giant cloud of pepper. It rises, dips, and turns as if it were a single, living thing. But it’s not. It’s made up of thousands of individual birds, flying and changing direction in unison.

Swoosh! From high above, a peregrine falcon dive-bombs the blackbirds, hoping to make one of them its meal.

But with so many eyes watching for danger, the blackbirds spot the attack. The flock peels apart, and the falcon whooshes harmlessly in between.

Teamwork Makes the Den Work

Construction is a family business for beavers. Mom, pop, and the kids work together to gnaw down trees and nip off branches. They haul the bark-covered building supplies to the water and stack them up to form a dam. Handfuls of mud help plaster the branches in place. When the dam is finished, water pools behind it, forming a wetland. Soon, the new habitat hums with life as ducks, herons, and muskrats move in.

Race to the Grave

American burying beetles eat dead animals. Mouse-sized morsels get eaten on the spot. Larger animals are saved for later.

Working together at night, two beetle parents use their heads to bulldoze soil out from under a corpse. Inch by inch, it sinks into a shallow grave. This isn’t easy for a thumb-sized insect. If you think it is, try burying a car using only your hands!

Once it’s buried, the female lays eggs on top of it. When the eggs hatch, the parents feed the meat to their babies.

Hunger Games

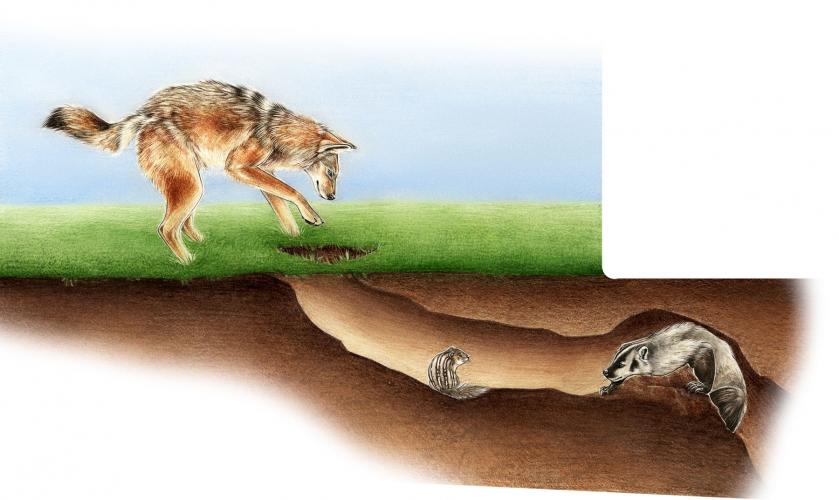

Coyotes have been known to team up with American badgers to bag snacks. The toothy teammates spell double the trouble for ground squirrels and other tunnel dwellers. Why? If a squirrel hunkers down in its hole, the burly badger digs it up for dinner. But if the squirrel scurries out of its burrow, the crafty coyote is waiting at the entrance to snap it up.

Huddle Up!

Southern flying squirrels can’t pack on fat for winter like other squirrels. If they did, they’d be too heavy to glide. So when temperatures plummet, the little forest flyers crowd into tree cavities and snuggle together to keep cozy. Their furry bodies can warm a den by 30 degrees. Nineteen squirrels have been found denning together in Missouri, and 50 were packed into a single tree in Illinois!

Follow the Leader

Turkey vultures have super sniffers that they use to find dead animals to dine on. Black vultures, like most birds, can’t smell squat. To find food, black vultures soar in large flocks until they see a turkey vulture descend. Then, the black vultures quickly drop and pile on the carcass, using their numbers to bully the turkey vulture off its dinner. When the feeding frenzy ends, the turkey vulture returns to snap up any scraps that remain.

V for Victory

Geese fly in a “V” for a reason, and it isn’t to avoid goosing each other. By flying in a wedge, geese in the front slice through the air and block the wind for geese flying in the back. This helps members of the flock save energy during long migration flights. When the goose at the front gets tired, it drops back and lets a different honker be the leader.

Scoop and Score

When an American white pelican wishes for fishes, it gathers a few buddies to help catch them. The brawny birds paddle through the water as a group, splashing their wings to herd fish into the shallows. Once the school is surrounded, the birds use their great big beaks to scoop up fish.

Dangerous Defense

If there were a trophy for best defense, these wasps would win it. When a predator digs up a yellow jacket nest, worker wasps swarm out. Each worker’s business end is tipped with a sharp stinger that the wasp stabs into the attacker over and over. When they sting, yellow jackets release odors called “alarm pheromones” that rally even more wasps to attack. Large nests can contain 2,000 angry yellow jackets, which is more than enough to stop most predators.

Playing the Odds

Large schools of fish, like these gizzard shad, use numbers to their advantage. In a small school, a predator has fewer fish to pick from, so each little fishy has a higher chance of taking a one-way trip down a pelican’s pie hole. But in a large school, a predator has more choices, so each fish has a much lower chance of being eaten.

Also In This Issue

Pull on your snow boots for a nature-filled hike.

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Alexis (AJ) Joyce

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Noppadol Paothong

David Stonner

DESIGNERS

Marci Porter

Les Fortenberry

ART DIRECTOR

Cliff White

EDITOR

Matt Seek

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Laura Scheuler

MAGAZINE MANAGER

Stephanie Thurber