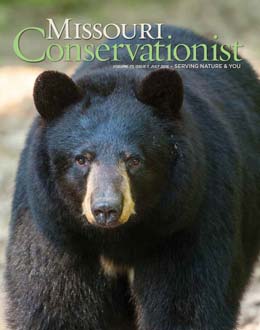

Most people have a healthy respect for bears. Wildlife Biologist Jeff Beringer does, too. In fact, he has a keen appreciation for the species’ remarkable intelligence, charisma, and strength.

But those natural feelings of wariness and respect haven’t prevented him from crawling head first into bear dens, armed with only a needle and a vial of rapid-acting anesthetic. For Beringer, a Missouri Department of Conservation resource scientist, it’s just another day at the office.

“I tell everyone, ‘Never corner a bear. Always give them an escape route.’ And then I crawl into a den that may have a mother and cubs,” he said. “Yes, sometimes there’s adrenaline pumping.”

For several years, Beringer has been conducting a longterm research project designed to discover more about Missouri’s American black bear (Ursus americanus) population.

“Our research, when combined with input from the public, will enable us to manage bear populations as they expand to fill available habitats, while ensuring they don’t become overabundant,” he said.

Bears Gain Ground in the Ozarks

For years, biologists believed black bears were extirpated from Missouri. Recent DNA evidence indicates a remnant population may have survived unnoticed, only to be bolstered by a reintroduction effort 57 years ago when bears were released into Arkansas from Minnesota and Manitoba.

“DNA from the remnant population is different than DNA collected from bears in other parts of Missouri and Arkansas,” Beringer explained. “Coloration is also different. In southwest Missouri, we often see black bears with a white-chest blaze, while our other bear populations have varying degrees of black, brown, and cinnamon colored coats.

“However, the remnant theory is unproven, and will remain so, unless we happen to find some DNA from an archived bear skull or bones.”

Today, it appears Missouri’s black bear population is tentatively expanding, primarily because habitat has improved. That wasn’t always the case. For decades, during the late 1800s and early 1900s, frontier logging of old growth forests was unregulated in the Ozarks. Free-range livestock was common, and wildlife regulations were weak or nonexistent.

“You could hunt bears year around,” he said. “When acorns hit the ground, bears had to compete with free-range cows, hogs, and goats for them. Those were tough times for a lot of our wildlife.”

Since that era, cutover forests have matured, allowing Missouri’s woodlands and forests to offer greater quantities of high quality mast (acorns and other tree nuts).

“We think we know how many bears are out there. Now we want to know how fast that population is growing,” Beringer said. He noted city officials often attempt to predict future human population growth trends to adequately plan for schools, roads, and public safety. The analogy holds true for Missouri’s bears, which need their own version of infrastructure, he noted.

“And that means habitat,” he explained.

Bears Once Flourished Here

Once found in abundance, black bears were staples for early settlers who relied on them for their meat, fat, and skins. Many early county histories contain reports of the remarkable number of bears in all areas of the state. Second only to deer, bears were the most common animal harvested by pioneers and travelers.

Obviously, modern-day Missourians no longer rely on bears for survival.

But flourishing, healthy populations of wildlife continue to offer benefits to humans — economically, aesthetically, and spiritually. The idea that wildlife is universally important to the lives of people — and people should have access to it — is a fundamental tenet of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, which declares wildlife is owned by no one, but is held in public trust for the benefit of every generation.

A Healthy Balance Between Humans and Wildlife

Missouri currently has 3 million acres of bear habitat, most of it publicly owned. Researchers are trying to determine the sweet spot for the size of Missouri’s bear population. “If bear populations get too dense, we’re going to have more bear and human conflict,” Beringer said. “We need to be able to predict where this population will expand.When do we need to start managing bears?”

Conservationists sometimes use the term “social carrying capacity” to describe the public’s tolerance, or intolerance, for wildlife. Although researchers have not yet surveyed Missourians to discover what level of interaction residents might accept, Beringer thinks it’s important to plan ahead to ensure that bears and people can continue to coexist.

Knowing the number of bears on the landscape, and understanding where they exist, will help reduce conflict, he said. Armed with accurate information, Department staff can better assist communities where bears are prevalent.

Like white-tailed deer, bears are harvest-limited, meaning in the absence of a harvest, their populations will eventually grow to levels incompatible with humans. “Bears can live a long time once they reach adulthood,” Beringer said. “Without management, bear populations

would grow and so would conflicts. We have to find the happy medium. Having too many bears for the habitat is unfair for bears and their human neighbors.”

Eventually, if bear numbers continue to increase, Beringer foresees scheduling a hunting season in the state.

The Missouri Black Bear Project

Researchers with the Missouri Black Bear Project are working to estimate the survival, recruitment, and movement of black bears. Data from this project will be used as baseline information for a comprehensive black bear management strategy.

The project is a cooperative effort with Mississippi State University and is funded through a Wildlife Restoration grant.

In the first phase, researchers captured animals and equipped them with GPS collars to determine home range and reveal where bear populations exist in Missouri. “Based on this information, we formulated a plan to estimate the state’s population of black bears,” Beringer said.

It’s hard to estimate bear numbers, since the animals occur at low densities, are secretive, and seldom spend a lot of time in one place. The Department’s telemetry study revealed female bears annually cover more than 40 square miles and male bears cover 100 square miles. Beringer estimates 350 bears, spread across approximately 20 counties south of Interstate 44, reside here. Scientists arrived at that estimate through a bear hair snare, a simple device designed to steal a few hairs from a bear as it crosses over or under a barbed wire fence to smell something strategically placed by biologists.

“Some folks say it’s like a burglar leaving their license at the scene of a crime. Bear hair collected on barbed wire at lure sites can tell a biologist exactly which bear was there,” Beringer added.

Over the course of two years, starting in 2010, nearly 800 hair snares covering over 1,500 square miles detected 141 different bears. Using this information, researchers estimated Missouri was home to 279 animals.

“We were able to use DNA to count bears without seeing or touching them,” he said.

Beringer thinks the population is trending upward, but bear populations do not grow fast. The species is dependent on older females to produce and raise cubs. If a female adult dies at age 5, she likely only added one or two bears to the population. If she lives to age 15, she may add as many as 15 bears to the population, depending on how many cubs survive.

“We’re seeing high survival for adult females,” he noted. “We expect the bear population to increase and expand into new areas, but are not sure how fast this will happen. Our current research examining the survival and reproductive rates of female bears should provide some answers.”

The Second Phase

Determining cub survival is the variable researchers are hoping to nail down during this phase.

Measuring the age at which females have their first litter, how long they live, and how many cubs they raise, on average, will allow scientists to calculate the bear population’s growth rate. By pulling a pre-molar, researchers are able to determine some of that information. Collecting that data requires a cooperative effort between several Department divisions. Department employees trap female bears during the summer months, and Beringer and his crew outfit them with radio collars so their movements can be tracked and their winter dens can be visited.

Most bears don’t reproduce until they are 3 to 7 years old. They then breed every other year, raising cubs in alternate years.

For example, in 2014 Beringer’s team captured and radio-marked a female of breeding age. That winter they found her den and noted she had two cubs — one female and one male. They revisited the den again the following year, finding her and the female yearling cub, but noticing the loss of the male. Survival for that litter was 50 percent.

The black bear study is testing three assumptions. First, 95 percent of adult bears are living from one year to the next. Second, females are averaging 2.2 cubs per litter, and third, females are typically 4 years old when they have their first offspring.

Beringer noted if 80 percent of cubs in Missouri are surviving, Missouri may have 500 bears by 2018. If fewer than half of Missouri’s cubs make it, the state won’t reach 500 cubs until 2030.

The second phase is a 7-year project, currently in its second year.

“Over time, if we visit an adequate number of dens, we’ll get a feel for overall cub survival, and this will help us predict how fast the overall bear population is growing,” he explained. “So far, we are seeing good survival for adult female bears, but we haven’t visited enough dens to accurately assess cub survival.”

He feels the Missouri landscape could sustain more than 1,000 bears. “We have a lot of habitat, mostly on public land,” he said.

For more information about the Missouri Black Bear Project, visit fwrc.msstate.edu/carnivore/mo_bear

Be Bear Aware

Although bears almost never attack people, taking a few precautions is sensible. By following these guidelines to “Be Bear Aware,” humans will be able to stay safe in bear country and keep Missouri’s bears wild.

First, hikers and campers should stay alert and avoid confrontation. By making noise — clapping and talking loudly — and traveling in groups, people can better ensure they don’t startle a bear.

It’s also a good idea to keep pets leashed. If a hiker or camper does encounter a bear, it’s best to back away slowly with arms raised. A calm, but loud, voice works best.

“Walk away slowly, but do not turn your back to the bear and do not run,” Beringer advised.

Additionally, with their powerful sense of smell, odors attract bears, so it’s a good idea to keep a clean campsite and store all food, garbage, and toiletries in a secure vehicle or strung at least 10 feet high between two trees. Unfortunately, a fed bear is a dead bear, so never feed bears, on purpose or by accident. If you live or camp in bear country, don’t leave pet food sitting outdoors. Clean barbecue grills and store them indoors. Don’t use birdfeeders from April through October in bear country. Store garbage securely until trash day. Use grounded electric fencing to keep bears from beehives, chicken coops, vegetable gardens, orchards, and other potential food sources.

Feeding bears makes them lose their natural fear of humans and teaches them to see people as food providers. They will learn to visit places like homes, campsites, and neighborhoods to look for food, instead of staying in the forest. Bears that have grown accustomed to getting food from humans may become aggressive and dangerous. When this happens, they have to be destroyed.

“Help bears stay wild and healthy, and keep you and your neighbors safe,” Beringer said. “Don’t feed bears.”

Also In This Issue

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Art Director - Cliff White

Associate Editor - Bonnie Chasteen

Staff Writer - Heather Feeler

Staff Writer - Kristie Hilgedick

Staff Writer - Joe Jerek

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Designer - Les Fortenberry

Designer - Marci Porter

Designer - Stephanie Thurber

Circulation - Laura Scheuler