Last year, someone mentioned that the Missouri Natural Area (NA) program began in 1970, when the Department of Conservation set out to preserve the best examples of the Show-Me State’s natural communities. That got me thinking how few of the 180-plus natural areas I had visited. Part of my job is helping people connect with places like these. You can’t do that without leaving the office. Visiting every NA wasn’t practical, so I decided to visit a sample of these remarkable places and then report on what I found.

Why Natural Areas?

Missourians spent a century taming their wild lands. Why try to save leftover bits and pieces?

Think of forests, prairies, glades, and swamps as libraries. On their shelves are plants and animals whose DNA holds all the ways nature has devised to survive on Earth. Each species is a book containing information found nowhere else. And there is much left to learn about how species interact within their natural habitats.

Allowing every acre of Missouri to be converted to cropland, subdivisions, cities, and highways is the same as discarding most of the books in a priceless and irreplaceable library. We would have plenty of corn, tulips, and cars, but nothing else. Where would we turn for new, life-saving drugs? For plants resistant to pests? For birdsong and butterflies to inspire composers and artists?

Natural Areas include the best — and sometimes the last — examples of Missouri’s original forests, prairies, glades, fens, swamps, caves, streams, and geologic features. All but 11 are open to public access. Most of those owned by the Department of Conservation or the USDA Forest Service are open to hunting and fishing. To plan your visit to one or more, visit mdc.mo.gov/node/2453.

Fifty of Missouri’s most interesting natural areas are profiled in Discover Missouri Natural Areas: A Guide to 50 Great Places, by Mike Leahy, the Conservation Department’s natural areas coordinator. This 140-page guide to natural features, plants, animals, and points of interest includes numerous color photos and costs just $9 plus sales tax and shipping and handling. To order, call toll free 877-521-8632 or visit mdcnatureshop.com. Or buy your copy at one of the Department of Conservation’s nature centers or regional offices and save shipping and handling charges.

Oldest

Clifty Creek

- Size: 230 acres

- Location: Maries County

- Designated: 1971

- Owner: The L-A-D Foundation

I arrived at Missouri’s oldest NA on a January morning that marked the end of a cold spell. The wet bluffs along the area’s namesake stream were shrouded with ice flows, and the surface of the creek was a fantastic abstract charcoal drawing.

Not everything was monochrome, however. The area’s steep valleys were carpeted with verdant moss and festooned with clumps of Christmas ferns. The occasional cardinal flitting among the greenery recalled the recent holidays.

The 40-foot span of the dolomite natural bridge over Clifty Creek stood out with particular starkness in the winter landscape. It was near noon by the time I finished photographing this remarkable feature, so I broke out cheese, crackers, and venison summer sausage and soaked in the view over a leisurely lunch.

After noon, the temperature climbed into the 40s, forcing me to shed fleece layers while negotiating switchbacks on the 2.3-mile loop trail. Crows, chickadees, and pileated woodpeckers provided the soundtrack for the hike back to my truck. Even with time spent taking pictures and notes, I was home by late afternoon.

Newest

Ha Ha Tonka Oak Woodlands

Size: 2,995 acres

- Location: Camden County

- Designated: 2012 (1991)

- Owner: Missouri Department of Natural Resources The contrast between Clifty Creek in winter and this area in summer is stark. Shimmering heat replaces the shimmer of ice, and baked, rocky glades stand in for verdant hills.

The 1834 surveyor’s notes for this area describe it as “flinty,” “bald,” and “unfit for cultivation.” But the surveyor failed to note 500 species of native plants flourishing in 13 distinct natural communities. Bird life includes species of continental concern, such as the blue-winged and prairie warblers.

When I visited in July, the blaze of spring wildflowers along the 0.9-mile Acorn Trail had died down to a smolder of coneflower, goldenrod, and bee balm. By midmorning the heat was oppressive, and I was glad to move to the shade of the 1.7-mile Quarry Trail. You can reach this loop by boat, using a courtesy dock at Mile 14.5 on the Niangua Arm of Lake of the Ozarks.

Part of this area was designated as an NA in 1991. An expansion in 2012 tripled the area’s size and led to its re-designation, making it the newest part of the system when I was there. Other areas have been added to the system since then and continue to be added.

SMALLEST

Grassy Pond

- Size: 1 acre

- Location: Carter County

- Designated: 1971

- Owner: Missouri Department of Conservation

If I had been on my own, I would have mistaken Missouri’s smallest NA for a man-made wildlife watering hole. Fortunately, I was with Natural History Biologist Susan Farrington, who pointed it out, noting that the tiny sinkhole pond was holding water for the first time since the awful drought of 2012.

Grassy Pond owes its survival to such dry spells, when fires sweep through the woods, killing woody undergrowth. This prevents the pond from being swallowed up by trees. Even with periodic drought and fire, it’s hard to see the pond for the brush. A thicket of buttonbush provides footholds for cypress-knee sedge, a plant that gets all its nutritional needs without soil.

The area also is home to frogs, salamanders, and such state-imperiled plants as bristly sedge, Engelmann’s quillwort, feather foil, sharp-scaled manna grass, and floating foxtail grass. The area’s most striking feature is rose mallow, which blooms in extravagant profusion here in late summer. With 8-foot stalks and multiple saucer-sized blossoms, the display is something to behold.

“Grassy Pond is a little world of its own,” says Farrington. “Even though it’s a tiny area, it has a lot of cool stuff. What gets me is how it goes straight from dry chert woodland to wetland.”

Largest

St. Francois Mountain

- Size: 7,028 acres

- Location: Iron and Reynolds counties

- Designated: 1996

- Owner: Missouri Department of Conservation and Missouri Department of Natural Resources

The St. Francois Mountains are among the oldest landforms on Earth, dating back 1.5 billion years, to a time when volcanoes erupted in the sea that then covered much of Missouri. This NA has waterfalls; scattered, enormous granite boulders; Missouri’s highest point; several state parks (SPs) and conservation areas (CAs); and a dizzying array of natural communities. I spent four days here in May and barely scratched the surface of its trails and stunning vistas.

I was lucky to arrive the day after a rain and found Mina Sauk Falls cascading 132 feet to the creek below. I had the trail almost all to myself that Thursday afternoon. The only exception was a 3-foot timber rattlesnake that was sunning on the bare rock path.

I saw migrating warblers and wildflowers too numerous to describe. Visiting Johnson’s Shut-Ins SP, I was astonished at its recovery from the collapse of Taum Sauk Reservoir in December 2005. Elephant Rocks SP provided a great place to eat lunch.

Features that will have to wait for my next visit include the Devil’s Tollgate, Taum Sauk Mountain’s 1,772-foot peak, 12 miles of the Ozark Trail, and the stark beauty of Ketcherside Mountain CA.

Wettest

Allred Lake

- Size: 76 acres

- Location: Butler County

- Designated: 1982

- Owner: Missouri Department of Conservation

Allred Lake is a tiny remnant of the vast cypress swamp that once cloaked Missouri’s Bootheel Region. You can still see ledges cut into the bases of giant cypress stumps where loggers placed planks to stand on while using 8-foot crosscut saws to fell swamp monarchs. The loggers left standing equally ancient cypresses that had less commercial value because of flawed trunks.

These remaining trees were old in 1541, when Hernando de Soto scoured the region for gold and a new route to China. To paddle a canoe among massive knees of these giants at sunrise is to glimpse the primeval wilderness that de Soto and his conquistadores beheld. Swamp darters, green tree frogs, western lesser sirens, and swamp rabbits still haunt this mysterious piece of not-quite land, nor yet water.

Driest

Dave Rock

- Size: 44 acres

- Location: St. Clair County

- Designated: 1987

- Owner: Missouri Department of Conservation

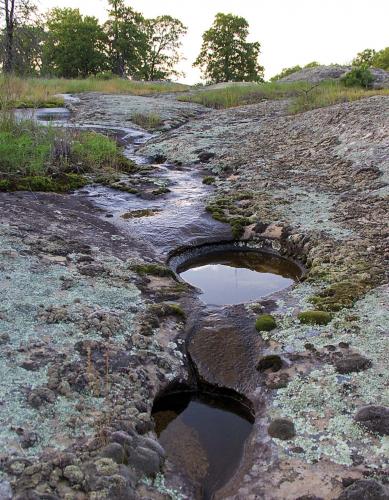

The only water you are likely to find on these areas is in shallow puddles after a rain. True to its name, Dave Rock has a 15-acre sandstone dome that is made to order for a family picnic, with plenty of smooth rock for kids to scramble around. They will be intrigued by tiny erosion canyons and round basins that runoff has carved in the soft sandstone. The edges of the dome are decorated with a lacework of moss and lichens that somehow maintain toeholds on the bare rock. Keep a sharp eye out and you might spy a 4-foot eastern coachwhip snake or a prairie racerunner lizard.

Driest

Lichen Glade

- Size: 26 acres

- Location: St. Clair County

- Designated: 1975

- Owner: The Nature Conservancy

Lichen Glade was awash in allium, black-eyed Susan, spiderwort, and great-spangled fritillary butterflies when I visited in June. A gentle breeze made the whole area look like a wavy pastel sea. Charred cedar stumps and limbs attested to the effectiveness of fire in defending these glades against woody invasion. Where they can sink a taproot into a crevice, tenacious eastern red cedars survive for hundreds of years. Pruning by wind, drought, and fire impart shapes that a master bonsai gardener might envy.

Most Rugged

Caney Mountain

- Size: 1,330 acres

- Location: Ozark County

- Designated: 1990

- Owner: Missouri Department of Conservation

Rugged is too mild a word to describe this uncompromising chunk of real estate. Serious hikers can scale High Rock, Bear Cave, Tater Cave, and Long mountains. Birders are always watching for the rare Bachman’s sparrow on glades. Prairie warblers, yellow-breasted chats, blue-winged warblers, collared lizards, and scorpions also inhabit glades. And don’t be surprised if you glimpse a roadrunner zipping across the rocky landscape in search of lizards.

Caney Mountain has history, too. Gazing out over Long Bald, with its riot of coneflowers and butterflies, gives you a spectacular view of the Gainesville Monadnocks, conical peaks that explorer-journalist Henry

Rowe Schoolcraft glimpsed on his storied tour of the area in 1818. A mile from the area’s east entrance is a log cabin where Starker Leopold, the eldest son of conservation luminary Aldo Leopold, stayed while developing Missouri’s first turkey restoration plan. This rugged landscape harbored some of the state’s last surviving turkeys before creation of the Department of Conservation. Turkeys live-trapped here became seed stock for Missouri’s enormously successful turkey restoration program.

Flattest

Taberville Prairie

- Size: 1.360 acres

- Location: St. Clair County

- Designated: 1971

- Owner: Missouri Department of Conservation

A summer sunrise on Taberville Prairie is heard as much as seen. Dickcissels, indigo buntings, bobwhite quail, and Bell’s vireos begin reciting soliloquies when daylight is only a promise in the east. Listen closely and you might detect the weird, burbling flute of a prairie chicken. As the sun steals up toward the horizon, clouds capture its yet-unseen rays and explode in incandescent mauve, pink, scarlet, and orange. Prairie rose, phlox, spiderwort, coreopsis, and pale purple coneflower wave in the chest-deep prairie grass, whispering a greeting to the day.

Gladey rock outcrops sport larkspur, allium, and prairie beard-tongue. Federally threatened geocarpon grows here, too. Standing on one of these barren patches, I spied a turkey vulture gliding straight toward me, barely 8 feet off the ground. I froze, and the bird, focused on the ground beneath him, came within 20 feet of me before realizing I wasn’t a tree and careened away in an undignified flap.

It seemed odd to find a marsh in the draw where Baker Branch flows. You can credit industrious beavers for this addition. I discovered a mourning dove nesting on the ground at the foot of an 18-inch cherry tree sprout but was sorry not to encounter any western slender glass lizards, Missouri’s only legless lizard.

Send me a picture if you see one.

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Managing Editor - Nichole LeClair Terrill

Art Director - Cliff White

Staff Writer/Editor - Brett Dufur

Staff Writer - Jim Low

Photographer - Noppadol Paothong

Photographer - David Stonner

Designer - Stephanie Thurber

Circulation - Laura Scheuler