Wilson's snipe is a well-camouflaged sandpiper-like bird with a very long bill, plump body, black- and white-streaked head, and relatively short legs (for a sandpiper). Upperparts are mottled brown and black with strong white streaks running down the back. The belly is white, and there is a rusty band near the tip of the tail. When surprised, snipe take off in a zigzag pattern and call a harsh “scraip, scraip.”

Similar species: The related American woodcock is an even pudgier member of the sandpiper family. It, too, is not usually seen on mudflats, but it prefers more wooded areas than the snipe. It also lacks the long whitish streaks on the back, its markings are less pronounced overall, with more gray on the back and with buffy or orangish underparts, and its legs are much shorter.

Length: 11 inches.

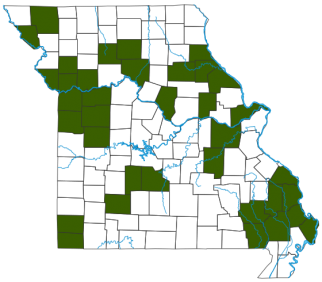

Statewide migrant. A few individuals may be present during the summer, although they are not known to breed in the state. Snipe are rare as winter residents, mainly in southern Missouri.

Habitat and Conservation

Though technically shorebirds, snipe are less associated with mudflats than most sandpipers. Snipe stay in moist grassy areas, swamps, shallow marshes, or in drainage ditches below ponds, sewer lagoons, or agricultural fields. You seldom see these shy birds until you are nearly upon them, when they abruptly rocket into the sky and fly away in a zigzag pattern. To hunters, they are a challenging target.

Food

Snipe forage at marshes, swamps, wet pastures, crop stubble, and drainage ditches for insects, crustaceans, and vegetation. As they poke their bills repeatedly into the mud, probing for invertebrates, their bobbing heads look something like a sewing machine. Like the related woodcock, their bills have a sensitive, flexible tip that can open to grip food while the rest of the bill remains closed.

Status

Common migrant; game bird. The snipe that live in North America used to be named common snipe (G. gallinago), which was long considered a circumpolar (global) species. Our subspecies of common snipe was called Wilson’s snipe (G. gallinago delicata). But in 2003 ornithologists determined that Wilson’s was distinct enough to be considered its own species. The Old World common snipe retains its name. You may run across older publications that call our species “common snipe.”

Life Cycle

Snipe are mostly seen in Missouri during spring and fall migration. Breeding occurs to our north, into Canada and Alaska, and they overwinter to our south, as far as northern South America. Like the woodcock, male snipes put on an aerial courtship display. They circle and dive above their territory in a “winnowing” display; air rushing over their tail feathers makes an eerie, pulsing, “hoo-hoo-hoo” sound. But you will probably not witness this in Missouri, where snipes do not breed.

Human Connections

These erratically flying game birds offer hunters a challenging target. More than 100,000 are shot in the United States a year. The term “sniper” originally referred to a snipe hunter, able to hit difficult targets, and became a term for a skilled military shooter firing from a hidden vantage point.

Ecosystem Connections

Snipe are predators and contribute to controlling populations of the invertebrates they eat. They are hunted by many animals (including people). Like killdeer, these ground-nesting birds try to distract predators from their vulnerable nests and young by flopping around and feigning a wing injury.

About 350 species of birds are likely to be seen in Missouri, though nearly 400 have been recorded within our borders. Most people know a bird when they see one — it has feathers, wings, and a bill. Birds are warm-blooded, and most species can fly. Many migrate hundreds or thousands of miles. Birds lay hard-shelled eggs (often in a nest), and the parents care for the young. Many communicate with songs and calls.