Snakeheads belong to a pair of closely related genera of long, cylindrical fish from Asia and Africa: genus Channa and genus Parachanna. Globally, there are about 30 species; all have a large mouth and sharp teeth, large scales atop the head, and eyes located far forward on the head — making their heads resemble those of snakes.

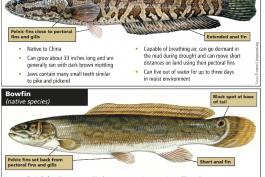

The northern snakehead (C. argus) is the species most likely to be found in Missouri. The markings may vary, but they are generally tan with dark brown mottling. The jaws contain many small teeth, similar to those of pike and pickerel. The top of the head is typically indented (concave). Both dorsal and anal fins are extended and long. The pelvic fins are located forward on the body, near the pectoral fins.

Key identifiers:

- Both the dorsal and anal fins are elongated

- Pelvic fins are located close to pectoral fins and gills

- No black spot at base of tail

- Many small, sharp jaw teeth

Similar species: North America's native bowfins (Amia ocillicauda and Amia calva) are also cylindrical, can grow large, and have a large mouth and long dorsal fin. They are found in many of the same habitats, too. But they tend to be more olive-colored and have a black spot at the base of the tail (especially A. ocillicauda, which lives in Missouri), and they have peglike (not pointy) jaw teeth. Also, look at the fins:

- Snakeheads have a long and extended anal fin, which is the bottom fin closest to the tail (the northern snakehead species has some 30–32 rays). The native bowfins have a short anal fin of some 9–10 soft rays. (Think of “bowfin” as singular: only the dorsal fin is elongated, not both dorsal and anal.)

- Snakeheads have the pelvic fins (the paired fins on the bottom of the body) located forward on the body, close to the pectoral fins (the fins just behind the gill covers). Bowfins have the pelvic fins located farther back, near the belly.

Adult length: can grow to about 33 inches; weight: commonly up to 10–12 pounds. Catches of invasive northern snakeheads in the United States have reached nearly 20 pounds.

As of 2023, two snakeheads have been found, in southeastern Missouri.

Habitat and Conservation

The favored habitat for the northern snakehead is in shallow, stagnant water with muddy substrates and somewhat dense aquatic vegetation. This fish also occurs in slow-moving, muddy streams, both large and small, drainage ditches, rivers, ponds, reservoirs, and lakes.

Snakeheads are native to Asia and Africa. When introduced to North American waters, they damage the ecological balance. They compete with native species for food and habitat. Lacking their natural predators, these large, fast-growing, fast-reproducing fish become the top predators and may potentially lead to a decline in our bass, crappie, and other fish populations. The impacts of this species on native fish populations are still to be determined and need to be monitored.

Another concern is that snakeheads may potentially transfer diseases and parasites to our native North American fishes.

Food

Snakeheads are predatory fish. Young snakeheads start out life eating tiny, drifting animals (zooplankton) and progress to larger and larger prey: aquatic insects, snails, crustaceans, and small or young fishes. They eat any prey that can fit in their wide mouths. A mature snakehead feeds almost exclusively on other fishes (which make up more than 97 percent of the diet). The remainder of the diet comprises crustaceans, frogs, small reptiles, and sometimes small birds and mammals.

Status

Invasive. Snakeheads are on Missouri's Prohibited Species List, and live fish and viable eggs may not be imported, exported, transported, sold, purchased, or possessed in Missouri. Do not release the fish or toss it up on the bank, because it could migrate back to the water or to a new water body. Remember, this fish is an air breather and can live a considerable amount of time out of the water. Kill the fish by severing the head, freezing the fish, or putting it on ice for an extended period of time. Photograph the fish, so the species can be positively identified. Report any sightings of this invasive fish to MDC's Southeast Regional Office at 573-290-5858.

The second verified catch of an invasive northern snakehead in Missouri was on May 19, 2023; it was captured by an angler who was seining for bait at Duck Creek Conservation Area in Wayne County; the snakehead was 13 inches long and estimated to be about 1 year old. The first northern snakehead recorded in Missouri was caught in a borrow ditch within the St. Francis River levees in Dunklin County in 2019.

Since October 2002, live snakeheads have been banned (under the federal Lacey Act) from import and interstate transport without a special permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Several U.S. states ban the possession of live snakeheads.

The northern snakehead has become invasively established in the Potomac River and threatens the Chesapeake Bay watershed. It also has been found in ponds, reservoirs, and other water bodies in several other states. If snakeheads invade the Great Lakes, they could cause great damage to that ecosystem.

In 2008, northern snakeheads were found in Arkansas drainage ditches, after an accident at a commercial fish farm. Flooding allowed these fish to move into the local White River, and from there, the fish made their way into the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers. They have been spreading north through the waters of the St. Francis River watershed.

In the past, snakeheads have sometimes been placed in these genera: Bostrychoides, Ophicephalus, Ophiocephalus, and Paraophiocephalus.

Life Cycle

Several aspects of the northern snakehead life cycle contribute to their invasive potential. First, they are capable of breeding up to five times a year, the females releasing some 50,000 eggs each time. They build a nest by clearing the plants out of a column of water about 2–3 feet in diameter. The adults stay with the nest and young for up to a month and vigorously protect them, increasing the survival rate of their offspring. The young grow quickly, so they rapidly attain a size which prevents them from being eaten by other predators, including herons and eagles. They can begin breeding at age 2 or 3. Their ability to breathe atmospheric air, to survive brief periods being out of water, and to move across land to new bodies of water magnifies their potential for spread.

Human Connections

The diet of snakeheads significantly overlaps that of the largemouth bass, which is a native game fish in Missouri. Potentially, northern snakeheads could compete with commercially and recreationally important fish species through predation and competition for food and habitat in ponds, streams, canals, reservoirs, lakes, and rivers. This can have economic consequences for our state, affecting tourism and fishing.

As with most other invasive species, humans are responsible for moving snakeheads from their native regions, where they have a place in balanced ecosystems, to places where their numbers can grow virtually unchecked. Before 2002, snakeheads were imported as a food fish and for aquarium hobbyists.

In their native regions, snakeheads are a valued food fish. In America — notably in Virginia and Maryland, where snakeheads have become invasively established in the Potomac River — anglers and bow fishers have been encouraged to catch and kill as many snakeheads as they want.

According to the Northern Snakehead Working Group (NSWG) of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, northern snakeheads likely arrived in U.S. waters by importation as live food fish. Unauthorized intentional release from this trade continues to be the major mechanism for introduction. The northern snakehead became widely popular in ethnic markets and restaurants over the last two decades, and that species constituted the greatest volume and weight of all live snakehead species imported into our country until 2001.

In some parts of our country, biologists suspect that snakeheads may have been released as a part of a spiritual ceremony traditional to some cultures — apparently, the northern snakehead's resilient nature made it more desirable than carps for ceremonial release.

Snakeheads may also have been intentionally released by people who had kept the fish as pets. Never release aquarium fish, plants, snails, or any other aquarium organisms into natural waters.

Ecosystem Connections

In their native lands, snakeheads fill the role of top predator in aquatic ecosystems. But where they are introduced and invasive, they can have a profoundly negative effect on ecosystems.

The diet of snakeheads overlaps the diet not only of largemouth bass but also of several other native fishes. This competition can disturb ecosystems in many types of aquatic habitats.

Various snakehead species have been introduced — on purpose, and by accident — in different regions of the world. The blotched snakehead (C. maculata) was introduced into the Philippines and Madagascar as a food fish, but now its invasive presence threatens several of Madagascar’s cichlid fishes (in the same family as angelfish, tilapia, and oscars) that are endemic to that island (found nowhere else in the world). The northern snakehead (the species invading the Potomac and starting to be found in Missouri) was also introduced into Japan as a food fish, and it was accidentally introduced into Russia and other central Asian countries.

The northern snakehead can breathe atmospheric air, which makes it capable of surviving in poorly oxygenated waters. It can adapt to a wide range of aquatic environments. For example, introduced populations in Asia and Japan successfully spread and reproduced in the shallow, low-oxygenated waters common throughout that region. This species would probably find many aquatic environments in the northern United States and southern Canada to be highly suitable, with abundant potential habitat in the Great Lakes.

The northern snakehead has many adaptations that could help it become established on our continent: it can overwinter easily, surviving under ice; it has a varied and flexible diet throughout all stages of its life; it is predatory and competitive; and it has high reproductive potential, with parental care increasing the offspring's survival rates.