Black gum, also called black tupelo, is a tall tree with horizontal branches and a flat-topped crown. Young trees are pyramidal; older trees more oval.

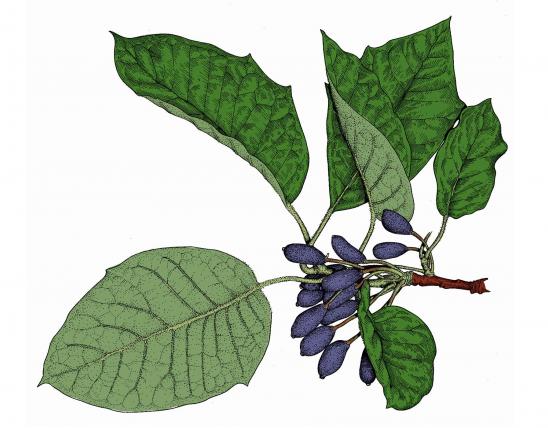

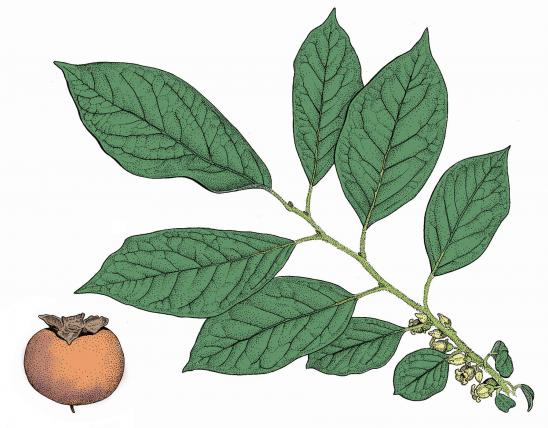

Leaves are alternate, simple, oval-elliptical, and lack teeth. In summer they are shiny dark green above and downy below. Often crowded toward the tips of branches. Early color changers, they turn bright scarlet or purple in late summer, well before the first frost.

Bark is gray to brown or black, deeply grooved, with ridges broken into irregularly shaped blocks with an “alligator hide” appearance.

Twigs are slender, reddish brown, slightly hairy at first, becoming gray and smooth later; some twigs short, pointed; pith white, with chambers.

Flowers April–June, as the leaves unfold. Male and female flowers greenish, in clusters on separate trees; petals 5, small.

Fruits September–October; plumlike, bluish black with a whitish coating, about ½ inch long, egg-shaped, thin-fleshed, with a single seed or pit. Pit flattened, with 10–12 broad, rounded ribs.

Similar species: Water tupelo (N. aquatica) develops a large, swollen base and the leaf margins are often irregularly toothed, the leaf tip abruptly pointed. Fruit is dark purple, thick-skinned, and dotted, in drooping clusters, each fruit about 1 inch long and widest above the middle. It occurs naturally in swamps with bald cypress trees in Missouri's southeastern lowlands and in two sinkhole ponds in the Ozarks.

Height: to 100 feet.

Mostly in the Bootheel and in the southeastern Ozarks, though it has become popular in landscaping throughout the state.

Habitat and Conservation

Occurs in acid soils overlying sandstone, chert, or igneous substrate of dry, rocky, wooded slopes, ridges, ravines, borders of sinkhole ponds in the Ozarks, and lowland forests in southeastern Missouri. It tolerates shade and is frequently found growing with or under oaks and pines.

Status

Native Missouri tree. Very popular in landscaping, with high ornamental, shade, and wildlife value.

Human Connections

Black gum is very popular as a landscaping tree. It offers an impressive, brilliant scarlet fall color and lacks the spiny balls of the unrelated sweet gum (with which it is sometimes confused, due only to the name). Another reason for black gum's popularity is that it is essentially pest-free; the few pests that attack it are not serious. Note that it is slow to become established after transplanting, so after-planting care is important. Once established, however, the trees require little care besides watering during drought. It also tolerates urban growing conditions.

The glossy, deep red autumn leaves are comparable to those of invasive Callery (Bradford) pear; black gum, however, is a native, non-invasive, larger, and much sturdier tree. As a great native alternative, black gum is helping people make the switch from invasives.

Black gum wood is used for veneer, plywood, boxes, pulp, tool handles, gunstocks, docks, and wharves.

Bees make good honey from black gum blossoms.

The fruit is edible but sour and has a large seed; some people eat them or make them into preserves.

Ecosystem Connections

Many animals eat the fruit: birds, small rodents, opossum, raccoon, foxes, deer, and black bear. The latter two also browse the foliage.

Black gum is the larval food plant for a beautiful noctuid moth called "the Hebrew" (Polygrammate hebraeicum). A striking white moth with numerous black markings, its caterpillars (which are also white with small dark marks) eat black gum leaves and, apparently, nothing else.

Black gums can help fight against habitat loss. When people get rid of their invasive Callery (Bradford) pears, they remove the sources of innumerable seeds that invade, take root in, and ultimately degrade native habitats. When they switch to native black gum trees, they help increase native habitat.

Large trees, in life and in death, provide habitat and nesting sites for many birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, insects, fungi, and more.