Ella Ewing Lake Conservation Area, in Scotland County, was purchased in 1967.

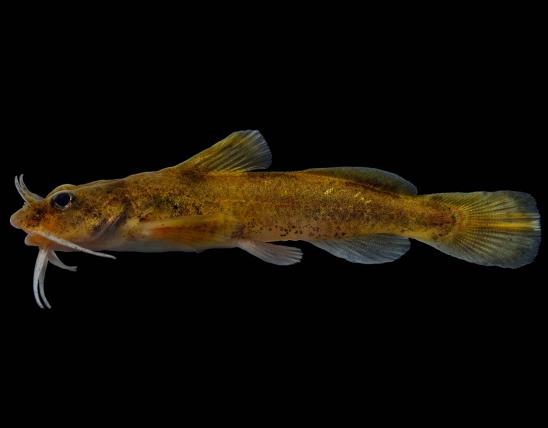

The black bullhead is widespread in Missouri. It is the most common bullhead catfish in north and west portions of the state. It has dusky or black chin barbels, and the edge of its tail fin is notched, not straight.

Bullhead catfishes, as a group, are chubby catfish that rarely exceed 16 inches in length. The upper jaw projects beyond the lower jaw. The tail is not noticeably forked. The adipose fin (on the back, between the dorsal fin and tail) is a free lobe, widely separate from the tail fin.

The black bullhead can be distinguished from Missouri’s three other bullheads by the following: The rear margin of the tail fin is slightly notched (not straight, and not deeply forked). The chin barbels are dusky or black (never uniformly white). The barbel at the corner of the mouth does not reach farther back than the base of the pectoral fin. The back and sides are not strongly mottled with a darker color. It lacks sawlike teeth on the back edge of the pectoral spine (you can check this by grasping the spine between the thumb and forefinger and pulling outward). The anal fin rays usually number 17–21 (fewer than our other bullheads). The length of the anal fin base is less than the length of the head (measured from tip of snout to outer edge of the gill cover).

Despite the name, it’s usually only the young, spawning males that are truly black; the more common overall coloration is dark greenish or yellowish brown. The back and sides are a uniform yellowish brown, dark olive, or black (not strongly mottled), with a pale vertical bar often evident across the base of the tail fin (such a bar is never present in other bullheads). The belly is yellowish or white. The fins are dusky or black, the membranes much darker than the rays. The upper tip of the tail fin is never lighter in color than the rest of the tail fin.

Similar species:

- The yellow bullhead (A. natalis) also has a wide range in Missouri, but it is better represented in the Ozarks and Bootheel lowlands. Its tail fin is straight (not slightly notched); it has sawlike teeth on the rear margin of the pectoral spine; anal fin rays usually number 24–27 (not fewer than 24); and the chin barbels are uniformly white (often slightly dusky in large adults from Ozark Streams, but not grayish or blackish).

- The brown bullhead (A. nebulosus) apparently has only one self-sustaining population in Missouri: at Duck Creek Wildlife Area and nearby Mingo National Wildlife Refuge in Bollinger, Stoddard, and Wayne counties. Another population occurs in a lake owned by the city of Arnold in Jefferson County. Its back and sides are usually strongly mottled rather than uniformly colored, and the barbel at the corner of the mouth is longer, reaching well behind the base of the pectoral fin in adults. Sawlike teeth are strongly developed on the rear margin of the pectoral spine. Anal fin rays usually number 22 or 23. Chin barbels are dusky or black. The rear margin of the tail fin is slightly notched, as in the black bullhead.

- The white catfish (A. catus, sometimes Ictalurus catus), another bullhead, shares the relatively short anal fin and blunt (not wedge-shaped) head of our other bullheads, but it has a moderately (though not deeply) forked tail fin. It commonly reaches 10–18 inches long; maximum about 24 inches. It’s not native to Missouri but is commonly stocked in fee-fishing lakes and other private waters. Where it has been occasionally collected from natural waters in Missouri, those individuals probably represent escapees. It has been collected in the Missouri and Mississippi rivers and the Big Creek arm of Truman Reservoir. It probably does not breed here, except perhaps in artificial ponds.

Adult length: seldom exceeds 16 inches; weight: seldom exceeds 2.3 pounds, with a maximum of about 4.75 pounds.

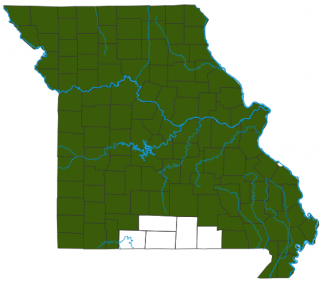

Widespread statewide. The black bullhead is better represented in the prairie region of northern and western Missouri than elsewhere.

Habitat and Conservation

Generally prefers turbid, silty water with little or no current.

The black bullhead is nearly statewide in distribution. It is the most abundant bullhead in many prairie streams of northern and western Missouri. It is less numerous than the yellow bullhead in most habitats of the Ozarks and Bootheel lowlands. It rarely occurs in main channels of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers but is abundant in overflow waters along their floodplains.

The black bullhead occurs in a variety of habitats but is most abundant in those with turbid water, a silt bottom, no noticeable current or strong flow, and a lack of diversity in the fish community.

Especially favorable habitats are the pools of small, intermittent creeks and the muddy oxbows and backwaters of larger streams in the prairie region of northern and western Missouri. Here, the black bullhead and a few other hardy species — such as the golden shiner, fathead minnow, and green sunfish — sometimes comprise the bulk of the fishes present.

In the Bootheel lowlands, it is common only in a few silty sloughs and in small, intermittent creeks draining Crowley’s Ridge.

The black bullhead occasionally achieves high population densities, with young continuing to school and forage together throughout their first summer of life.

Food

The black bullhead, like other catfishes, relies on an acute sense of smell to find its food. Young black bullheads feed primarily from the bottom on a variety of plant and animal material. One study showed the diet of adult black bullheads was principally immature aquatic insects, and young up 1 inch long fed almost exclusively on small crustaceans.

Adults are mostly inactive during the day but leave the deeper parts of pools to feed during the early hours of darkness, returning shortly before dawn. The young swim actively in schools during most of the daylight hours and exhibit two primary feeding periods: one around dawn and the other around dusk.

Status

Common.

Taxonomically, there are more than 35 catfish families in the world. All of Missouri’s catfish belong to only one of these families, the Ictaluridae. This family has been called the “bullhead catfishes” as well as the “common catfishes.” So just as it’s technically correct to call any plant in the sunflower family “a type of sunflower,” you could also call channel, blue, and flathead catfishes, plus all the madtoms, “types of bullhead catfishes.” However, it is more precise to restrict the term “bullhead” to members of the genus Ameiurus. Members of genus Ameiurus have blunt heads and squared tail fins with only a slight notch if any (as opposed to truly forked tails as in channel cats).

Life Cycle

Black bullheads spawn in May or June. The female excavates a saucer-shaped nest by fanning material out with her lower fins and pushing pebbles to the periphery with her snout. Nests often are located beneath logs or other large objects elevated above the stream bottom. One of the parent bullheads remains with the nest, fanning and aerating the eggs with the fins and warding off predators. Minnows and sunfish often hover near the nest, rushing in to eat eggs whenever an opportunity arises.

Upon leaving the nest, the young bullheads move about in a compact, ball-like school, accompanied by one or both of the adults. The balls of coal-black young bullheads are easy to see from shore as they move around near the surface. The adults abandon the young when they are about 1 inch long, but the young continue to school throughout their first summer of life. Few individuals live more than about 5 years in the wild.

Human Connections

Although purists may turn up their noses at the idea of angling for bullheads, these fishes provide many hours of fishing pleasure in waters where few fishing opportunities would otherwise exist. Still-fishing with a cane pole or rod and reel is the most popular method for catching them. Worms are one of the best baits. When fishing for bullheads, remember to fish on or close to the bottom.

Few people go “fish watching,” but this is one species to look for starting in May and June, when young black bullheads swim in schools and can be easily visible when they swim near the surface. Tips for fish watching: approach with caution; avoid anything that might cause the water to vibrate; maintain a low profile so you aren’t silhouetted against the sky; wear polarized sunglasses to diminish surface reflections; choose windless days so that the surface isn’t broken up; and consider using binoculars.

Ecosystem Connections

Fishes like the black bullhead, that continue to care for their young after hatching, exhibit some of the extremes of parental care among fishes. Parental care greatly increases their offspring’s chances of survival. Fishes are most vulnerable to predation when they are eggs and newly hatched fry.

In general, predators of bullheads include any fish large enough to consume them, plus watersnakes, snapping turtles, herons, and raccoons.

As a defense against predation, bullheads (like many other catfish), when attacked, typically stretch out and lock their dorsal and pectoral spines, which makes them much harder to swallow.

Worldwide there are more than 35 families of catfishes in the catfish order (Siluriformes). Most of us could easily identify most of them as “catfishes” by their whisker-like barbels, smooth bodies lacking scales, general nocturnal disposition, and typical bottom-feeding habits. But aquarists know that several tropical cats have bony plates (which still aren’t technically scales) — think “cory cats” (Corydoras spp.) and “plecos” (Hypostomus plecostomus). People who have aquariums may also be familiar with catfish that are not bottom feeders — think of the “glass catfish” (Kryptopterus) that swim in the middle level of an aquarium. Some other tropical freshwater catfish popular in the aquarium trade aren’t called catfish: one example is the “iridescent green shark” (Pangasius spp.), which you may also find frozen in groceries labeled as “swai,” “panga,” “basa,” or “bocourti.”