Xplor reconnects kids to nature and helps them find adventure in their own backyard. Free to residents of Missouri.

Stay in Touch with MDC news, newsletters, events, and manage your subscription

Xplor reconnects kids to nature and helps them find adventure in their own backyard. Free to residents of Missouri.

A monthly publication about conservation in Missouri. Started in 1938, the printed magazine is free to residents of Missouri.

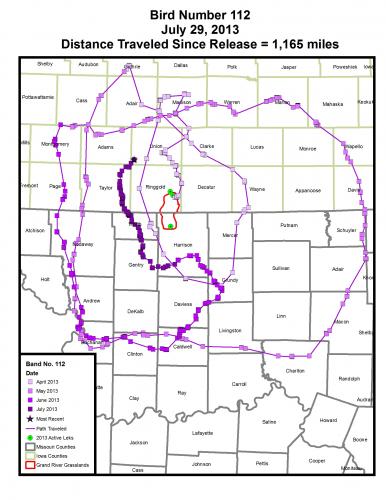

Kansas City, Mo. – A female prairie chicken wearing a GPS tracking collar surprised and puzzled biologists this summer by traveling 1,165 miles in big circles in southern Iowa and northern Missouri. The hen labeled Bird No. 112 was trapped in western Nebraska and released on April 4 in Iowa near the Missouri border, north of Bethany, Mo., for a prairie chicken restoration program. Since then, she has avoided fatal dangers such as predators, vehicles, fences and utility lines in a ceaseless journey that has slowed but not stopped.

“We don’t really know why,” said Jennifer A. Vogel, who has monitored Bird No. 112’s travels as a post-doctoral research associate at Iowa State University. “It seems like she was searching for something.”

Bird No. 112’s travels include: a northerly jaunt in Iowa after her release; a southerly loop into Missouri and then north back into Iowa; a visit to St. Joseph on Missouri’s western boundary; a swing east past Kirksville in the state’s north central region; a move back to Iowa and then flights past the bridges of Madison County southwest of Des Moines; a second trip to St. Joseph; a second visit to the Trenton, Mo., area; then a slow march back through northwest Missouri into Iowa where on July 29 she was feeding and nesting a couple of counties north of the state line near Kent, Iowa.

“It’s neat that she’s capable of traveling that far, but we hope all the hens don’t do that or we won’t get any reproduction,” said Len Gilmore, a wildlife management biologist for the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) who studies prairie chickens.

Biologists are not sure if some prairie chickens have always moved these distances, which would boost genetic diversity. Or, hen No. 112 may be looking for other prairie chickens and a landscape more resembling arid western Nebraska. Prairie chickens are endangered in Missouri. They were extirpated from Iowa by 1952 with only re-introduced birds there now in limited numbers.

Slightly more than 100 prairie chickens remain in Missouri where once hundreds of thousands once roamed. Their decline is primarily because less than one percent of the state’s native grasslands remain. Most of those birds are in two flocks in west central Missouri. MDC bolstered their numbers and genetic diversity in recent years with birds translocated from Kansas.

The good news is that a flock re-established at the Wah’Kon-Tah Prairie near El Dorado Springs, Mo., is holding steady with 40 to 50 prairie chickens. They had good nesting success this spring, said Tom Thompson, an MDC resource scientist. A couple of Kansas birds released at Wah’Kon-Tah Prairie in 2012 also did some traveling that surprised biologists.

One hen outfitted with a radio transmitter traveled south to Dade County this spring. She joined a male dubbed earlier as “Lonesome Chuck.” He was a lone survivor of the species at the prairie on the Wade and June Shelton Memorial Conservation Area. They produced offspring _ 13 eggs hatched _ and the hen is still alive and being tracked by biologists.

Another hen with a transmitter journeyed northwest of El Dorado Springs to a prairie remnant in Bates County and hatched chicks. She was later killed by an undetermined cause. But biologists see it as a positive sign that prairie chickens are not rooted to where they’re hatched or released, and that they will travel 30 to 50 miles to seek out remnant prairies or previously used leks, which are spring mating grounds.

“It’s encouraging to see that the birds from Wah’Kon-Tah can make it that far,” Thompson said.

The perilous, cross-state travel by Bird No. 112 in northwest Missouri is another matter. However, she may not be the only Nebraska-trapped bird roaming a long distance, but rather just the only one that biologists can track cross country. Iowa placed 10 solar-powered GPS satellite transmitters on hens released this spring. Only Bird No. 112 survives, as the others were killed by predators.

Bird No. 112 was among 73 prairie chickens from Nebraska released this spring in the Grand River Grasslands prairie focus area that spans the Iowa and Missouri state line. The 70,000 acre project is a partnership between MDC, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, private landowners and several other public and private conservation partners. Dunn Ranch, owned by The Nature Conservancy of Missouri, was the release point for birds on the Missouri side.

MDC staff attached radio transmitters to 16 hens that were released at Dunn Ranch along with seven males without radio collars. Tracking the hens helps biologists learn what kind of habitat prairie chickens prefer and what they need for nesting and brood rearing success. That information will guide habitat management decisions in the future.

However, the tracking collars used by MDC are not connected to satellites like those used on the hens released in Iowa. Staff must track those birds using antennas at relatively close range or with aircraft flyovers.

Three of the hens with MDC collars nested in the release area and two produced successful hatches. It’s positive that some of the Nebraska-trapped birds released this spring joined a handful of prairie chickens that were already using the Dunn Ranch lek, Thompson said.

But 10 hens with radio collars moved out of the area and their fate is unknown, said David Hoover, an MDC wildlife biologist. They may be on a long journey like Bird No. 112, or perhaps a shorter trip, and they hopefully will return. Bird No. 112 has passed south of the Dunn Ranch area twice.

“We’re still hoping they will show back up and produce broods,” Hoover said.